You have /5 articles left.

Sign up for a free account or log in.

More than a year and a half after a Minneapolis police officer killed George Floyd in May 2020, prompting a national reckoning about institutional racism and societal inequity, signs of change in higher education can be hard to spot. One place you might not have thought to look is behind the college president’s desk.

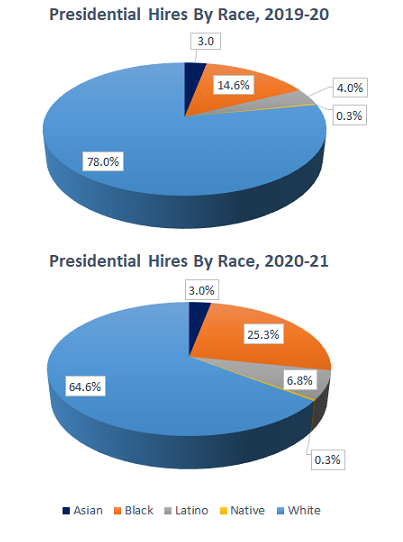

But in the 18 months from June 2020 through November 2021, more than a third—35.4 percent—of the presidents and chancellors that American colleges and universities hired were members of racial minority groups. A full quarter (25.3 percent) were Black, an Inside Higher Ed analysis of its database of presidential appointments shows; that figure is 22.5 percent when excluding historically Black colleges and universities.

By comparison, fewer than a quarter, 22 percent, of presidential hires in the 18 months from December 2018 through May 2020 were nonwhite. Just 14.6 percent of the campus leaders hired in that period before Floyd’s death were Black.

The proportion of Latino presidents also grew in the months after that June 2020 dividing line, to nearly 7 percent from 4 percent in the previous 18 months. There was no change in the representation of Asian or Native American presidents.

To the extent these crude data can be used to measure progress in the diversification of the college presidency, not all signs point up. The proportion of women who were hired, for instance, actually declined slightly, to 34.8 percent in 2020–21 from 35.3 percent in 2019–20.

But the women who were hired from June 2020 through November 2021 were more racially diverse (62 percent were white, 27 percent black and 8 percent Latina, compared to 72 percent white, 21 percent black and 4 percent Latina in the earlier period), and women of color made up 13 percent of all presidents hired from June 2020 to November 2021.

Experts on college and university leadership and on diversity in higher education attributed the increased hiring of minority leaders to several factors: intensified external pressure on colleges to diversify, related to the Black Lives Matter and racial justice movements; an expanded pipeline of minority candidates, due in part to a slew of long-standing and new programs aimed at preparing new leaders; a shift in the traits and competencies institutions are seeking in leaders; and changes in how and where colleges and universities search, to name several.

Letter to the Editor

A reader has submitted

a response to this article.

You can view the letter here,

and find all our Letters to

the Editor here.

“Maybe some of these initiatives we’ve put so much effort into are finally paying off,” said Lorelle L. Espinosa, program director at the Alfred P. Sloan Foundation and a longtime researcher on higher education diversity. “It may be that as institutions felt more pressure to get diverse candidate pools to respond to the racial reckoning, the individuals were there to be found.”

Others said that while the numbers might look heartening, “history tells us not to get too caught up in the current,” as Eddie R. Cole, associate professor of higher education and history at the University of California, Los Angeles, put it. Hiring more presidents of color is one thing, Cole said; “it remains to be seen what kind of support these presidents will receive in these positions, and whether they will have the autonomy to change how their institutions work.”

Presidential Diversity Over Time

Racial and ethnic diversity among college and university leaders has significantly lagged that of higher education enrollments, let alone of the U.S. population. A 2020 report from the College and University Professional Association for Human Resources found that more than 80 percent of college administrators were white, and only 13 percent of executive officers were members of racial minority groups.

The most recent national data on diversity among college chief executives come from the 2017 edition of “The American College President,” published by the American Council Education. That report found that 17 percent of presidents in 2016 were nonwhite, and 5 percent of presidents that year were women of color. The proportions were even lower when historically Black institutions were excluded. The council’s data showed relatively little change over the previous 15 years.

The underrepresentation of minority leaders has drawn significant attention for many years, especially amid growing recognition of the significant equity gaps in student access and success in U.S. higher education. That intensified in the wake of a spate of racial incidents and protests on campuses in 2015, and arguably peaked in the summer of 2020, when Americans were forced to confront the continued lack of racial justice and equity in American society.

“Why is it important for a university’s governing board, administration or faculty to reflect the increasingly diverse student body at colleges and universities?” Ajay Nair, president of Arcadia University, wrote in The Philadelphia Inquirer in 2019. “To provide a more accurate representation of the world. To serve as direct examples of success for a diverse student body. To ensure that diverse viewpoints are taught, represented, defended and considered within university decisions. To help sustain universities as they move forward with an evolving populace, an evolving curriculum, and an evolving world.”

The lack of progress in diversifying the college presidency has persisted despite increases in the number of programs designed to expand the pipeline of minority candidates, with numerous new institutes joining long-standing programs such as the American Association of State Colleges and Universities’ Millennium Leadership Institute and the ACE Fellows Program at the American Council on Education.

In the last few years, headlines about colleges and universities hiring their “first” minority president appeared to increase; 2020 brought appointments such as Michael Drake at the University of California system, Jonathan Holloway at Rutgers University, Darryll Pines at the University of Maryland at College Park, Suzanne Rivera at Macalester College and Lynn Perry Wooten at Simmons College. More followed in 2021, with selections such as William Tate IV as president of Louisiana State University, Brian Blake as president of Georgia State University, and Reginald DesRoches as president of Rice University.

Beyond the Anecdotal

To try to gauge whether those appointments represented a larger trend, Inside Higher Ed examined the lists it periodically publishes on newly appointed presidents and provosts and identified all new presidents appointed between Dec. 1, 2019, and Nov. 30, 2021—18 months before and after the murder of George Floyd.

That June 1, 2020, line of demarcation is admittedly symbolic and imprecise, given that search processes for presidents can stretch beyond a year. Inside Higher Ed analyzed material published about those presidents to determine how they identified racially. In a small number of cases where the identity was not evident, the presidents were excluded from the analysis. The analysis identified a total of 329 presidents and chancellors hired in the first 18-month period (2019–20) and 336 presidents in the second period (2020–21).

Of the 329 leaders colleges hired in 2019–20, 256, or 78 percent, were white, 14.6 percent were Black, 4 percent were Latino or Hispanic, and 3 percent were Asian. Even that represents modest upward movement from the last “American College President” study in 2017, when 83 percent of presidents were white.

Of the 329 leaders colleges hired in 2019–20, 256, or 78 percent, were white, 14.6 percent were Black, 4 percent were Latino or Hispanic, and 3 percent were Asian. Even that represents modest upward movement from the last “American College President” study in 2017, when 83 percent of presidents were white.

But the 2020–21 data suggest a more dramatic change, particularly in the hiring of Black presidents.

Of the 336 presidents hired from June 1, 2020, through Nov. 30, 2021, 25.3 percent were Black and 6.8 percent were Latino. Fewer than two-thirds (64.6 percent) were white, a marked decrease from the 78 percent in the previous 18 months and the 83 percent of all presidents employed by colleges and universities in 2017.

Breaking the data down further, public two- and four-year colleges hired the most diverse collection of leaders; respectively, 33 percent and 28.7 percent of the new presidents and chancellors they hired in 2020–21 were Black, and 58.3 percent and 56.3 percent were white. (The latter percentage rises to 60.5 percent when historically Black colleges are excluded.)

About three-quarters (74.3 percent) of the leaders hired by four-year private nonprofit colleges and universities during that 18-month period were white, and 19.5 percent were Black. White presidents made up 78.5 percent of the four-year-private college presidents hired when historically Black colleges were excluded.

By Carnegie classification, white presidents made up 56.1 percent of 2020–21 hires at associate-granting colleges, 61 percent at baccalaureate colleges, 63.6 percent at master’s institutions and 73.9 percent at doctoral-granting universities. More than a third (35 percent) of the universities at the highest level, doctoral institutions with very high research activity, appointed minority presidents; five of the 15 presidents selected at public universities at that level were Black.

Four of the 10 leaders hired by statewide college or university systems in 2020-21 were nonwhite.

Among other highlights of the data:

Gender. In 2016, according to ACE’s “American College President,” 30 percent of all presidents were women. Inside Higher Ed found that colleges hired roughly the same number and proportion of women in the two 18-month periods studied, about 35 percent of the total. But the female presidents who were hired in the 2020–21 period were more likely to be nonwhite than were their male counterparts. And at the community college level, white women represented a minority of those hired, 41.5 percent, followed closely by Black women (39 percent).

Previous jobs. Many presidents have historically been hired after previous experience as a president, and the provost’s role has also been a gateway to the top job. In 2016, according to ACE, more than three-quarters of presidents had been either a president or a provost or other senior academic administrator in their previous role.

Inside Higher Ed’s data for 2020–21 find that about a third had previously been a provost or other senior academic leader, and of those, 71 percent were white. More than a third of the hired presidents (about 125) had previously been a president, and of those, about two-thirds were white. More than 50 of those presidents, however, had been an interim president at their own institution, and 20 of those—a full 40 percent—were Black, Latino or Asian American.

Another noteworthy result is what appears to be an increase in hiring of presidents with a background in student services and student success. From December 2019 to May 2020, colleges and universities in the Inside Higher Ed sample hired about 20 presidents whose previous job had been as a vice president for student affairs or student success. Of those, about a third were from underrepresented minority groups. In 2020–21, by contrast, about 25 presidents came directly from senior student services positions, and about three-quarters of them were Black.

Geography. Hardly anything that happens in American society today isn’t influenced by, or evidence of, the divided nature of our politics. Looking at which institutions hired presidents of different races shows differences by state. About seven in 10 of the presidents hired by colleges in red states (those carried by former president Donald J. Trump in the 2020 election) were white, compared to about 59 percent of the leaders appointed by colleges in states won by President Biden.

What Experts Make of the Results

Inside Higher Ed ran its findings by a wide range of experts on higher education leadership and on campus diversity to elicit their views on the validity of the data, their significance and what they say (or don’t) about the state of the college presidency.

Lucy Leske, a senior consultant at the search firm WittKieffer, said the findings are consistent with what her firm is seeing: WittKieffer’s own internal data show that 32 percent of the people it placed into executive positions in higher education in the last two years were people of color.

Espinosa of the Sloan Foundation said she was unsurprised that minority hiring was likelier at community colleges than at more selective institutions, “which have been the least diverse in the ecosystem.” She noted that it has long been discussed in “circles of women college presidents” that they were most typically hired at struggling institutions where they were “being given an institution to turn around,” which doesn’t “set people up for success.” The hiring of Black and Latinx leaders at places like Rice, California’s university systems and flagship universities such as Maryland and LSU suggest at least the beginning of a change.

Leske and others attribute the apparent increase in hiring to a range of factors.

“First and foremost, it’s a pipeline issue,” Leske said. “The number of people who are prepared to take on senior leadership roles is steadily growing because of years and years and years of dedication by the academy, individual institutions and programs like ACE’s to hiring and promoting diverse talent. That takes decades, and we’re finally starting to see the results of all that work.”

Other analysts agree with Leske that there are more qualified minority candidates than ever before, and that programs designed to identify and prepare underrepresented minority candidates and women for presidencies had contributed greatly. Joseph Castro, who in 2020 was the first Mexican American appointed to lead the California State University system, cited the Executive Leadership Academy at the University of California, Berkeley’s Center for Studies in Higher Education as having influenced him and helping to guide the many young administrators he has sent its way for training.

But Castro also said the pipeline has expanded because more minority academics have begun seeing themselves as legitimate candidates for presidencies and putting themselves forward. Ajay Nair, the Indian American who became Arcadia University’s first president of color, seconded that notion. He said he first considered himself as potential presidential material during a conference panel at which several new presidents, many of them minority-group members, talked about their own paths to the presidency. “As more presidents of color enter these positions,” Nair said, “there’s a greater awareness that these positions are actually accessible.”

“There’s no doubt whatsoever that the social justice movement of the last couple years has forced the hands of many boards.”

--Lucy Leske, WittKieffer

Some of the traditional pathways to the presidency remain dominated by white men—particularly research vice presidencies, which have historically been filled by scholars in physical science fields where people of color and women remain underrepresented.

Loren J. Blanchard, who was appointed this year as president of the University of Houston–Downtown, said the Houston system is looking for a provost now. The search consultant told university officials that of the roughly 1,100 people in the pool they’re drawing from—deans, associate and assistant provosts at major research universities—“80 are Latinx, about 40 are African-American and a smaller number are Asian,” Blanchard said. “Not representative at all.”

So expanding the pipeline may also require governing boards, search committees and hiring firms to expand where they look for candidates, especially as the requirements of the presidency change, several experts said.

Leske, for instance, said she wasn’t surprised that more institutions appeared to be turning to candidates with student services backgrounds for presidencies. “The field of student affairs has changed dramatically,” she said. “This is not the person who’s throwing parties for students anymore. These student affairs professionals are deeply skilled at collecting and analyzing data and more closely tied to enrollment.”

Blanchard of Houston-Downtown was previously responsible for academic and student affairs at the California State University system. He saw several leaders with backgrounds in student affairs or student success chosen for campus presidencies at Cal State and believes that more colleges that see their primary missions as educating students—all students—may turn to people with backgrounds like his.

“More and more colleges elsewhere in the country are facing what we saw early on in majority-minority states like California and Texas, that access for all students is important, yes, but you also have to make sure that students, whatever their background, graduate with valuable degrees,” he said. “People who come out of the student affairs and student success side come with that orientation of understanding what is really needed not only to develop a strategic focus on student success, but on delivering on it.”

Beyond Pipeline

L. Song Richardson, who in early 2021 was named the first woman of color to lead Colorado College, doesn’t doubt that the pipeline of minority candidates has expanded, but she said that doesn’t come close to explaining the apparent upturn in hiring.

“We were always here,” said Richardson, who is Black and Korean American. “What I think has changed most is something about this current moment we’re in that allowed people, maybe forced people, to be far more intentional to consider and find leaders of color.”

“It’s not race that is driving boards to select presidents of color, but their understanding that they find presidents who know how to best serve those students who are coming in, more of whom are of color.”

--Loren J. Blanchard.

“There’s no doubt whatsoever that the social justice movement of the last couple years has forced the hands of many boards,” said Leske of WittKieffer. “It caught them as deer in the headlights, with the knowledge that we’ve been paying lip service to this for too long.”

Cole of UCLA said the pressure intensified after the University of Missouri’s disastrous engagement with Black students amid protests over police killings and other matters in 2015, and grew further after Black Lives Matter gained national recognition.

“It’s really difficult for a university to talk about diversity, equity and inclusion for students and faculty but at the same time have a leadership that looks almost completely white,” said Cole. “You can’t, in 2021, bring forth a set of finalists and say, ‘Hey, look at these all-white candidates.’ You just can’t afford terrible publicity like that.”

While Cole acknowledges that external pressure may not be the best reason for a behavioral change like this, he said Derrick Bell’s theory of interest convergence suggests that “it’s not necessarily a bad thing … if that’s what it takes [for] a hiring board to hire a racially diverse leadership.”

What Are Colleges Doing Differently?

Richardson of Colorado College and others spoke of boards and search committees being more “intentional” as they sought presidents. What are they actually doing differently?

It starts with process, said Leske of WittKieffer. “What makes a difference is whether the search committee is modeling inclusive behavior and using best practices that mitigate bias,” she said. Boards need to be committed to transparency in how searches are conducted, she said, and to widening the circle of who is included in the search process.

Espinosa of the Sloan Foundation likens the process to holistic admissions, in which colleges take a broader look at applicants’ credentials and experiences. “If you have the right people in the room, you’re more likely to see how certain skills are transferable [to strong leadership] in ways you might not have seen before,” she said.

Extending the holistic admissions analogy, Espinosa highlights the importance of reassessing the selection criteria to “recognize the need for this kind of leadership now,” given the growing diversity of today’s students.

“It’s not race that is driving boards to select presidents of color, but their understanding that they find presidents who know how to best serve those students who are coming in, more of whom are of color,” said Blanchard.

Once searches begin, one key is “not moving forward until you have a diverse pool,” said Richardson of Colorado College. She cited research showing that when there is only one female (or minority) candidate in a candidate pool, “the chances of that person being hired are fairly low, whereas if you have two, they’re better.”

Cautious Optimism, and Warnings

Most of the experts interviewed for this article found the increased hiring of minority leaders heartening. But few were giddy.

Eddie Cole’s book, The Campus Color Line: College Presidents and the Struggle for Black Freedom (Princeton University Press, 2020), explored how campus leaders responded to the civil rights movement of the 1950s and 1960s, and he sees plenty of parallels to the current moment. Universities felt intense pressure during that period to enroll Black students and address racial issues, and many of them did. But some of the changes they made weren’t undertaken with the best of intentions, and many of them did not last.

So forgive Cole if he remains skeptical about whether the greater hiring of minority presidents will be sustained—and whether the presidents hired now get the support they need to succeed.

“History tells us, don’t get caught up in the current,” he said. “We have to see what happens before knowing if these hires end up being important or just checking a box.”

That assessment will be influenced both by whether colleges and universities continue to hire increased numbers of underrepresented presidents and whether those being hired now succeed.

Bonnie Thornton Dill, dean of the College of Arts and Humanities at the University of Maryland, College Park, is helping to lead a $3 million Mellon Foundation project designed to increase the representation of arts and humanities scholars in academic leadership. She still worries about the pipeline of minority Ph.D.s, particularly in key scientific and other fields from which research universities often hunt for provosts and presidents.

“Sustainability will depend on producing more of those people and developing programs and initiatives that help them advance and develop a broader range of experiences on the campus,” Dill said.

Other experts wondered how fully boards will support the new crop of presidents.

Leske of WittKieffer said she sees evidence that minority leaders in politics and other realms have shorter honeymoons and have targets on their backs, such that “if they make a single mistake, people are far more likely to jump on them than they are on white men … That raises questions for me about whether candidates from nonwhite, minoritized communities have tenures that are as sturdy as what we’re used to.”

Richardson of Colorado College said board support is critical, especially given the extent to which they are expecting presidents to “do difficult things in a difficult time.” Support can come in the form of ensuring that new presidents have strong mentoring and honest sounding boards, said Cal State’s Castro.

It may also require institutions and boards to reassess how they spend money and to give them autonomy “to create the change that they say they want,” said Cole of UCLA. “Without that, these may be just symbolic.”

For Nair of Arcadia, institutions’ commitment to meaningful (and long-term) diversity in leadership may start with diversifying the board itself. “From my perspective, what I need to be successful is a board that is also diverse, that understands the moves we’re making as an institution related to justice, equity, diversity and inclusion,” he said. “I had to do a significant amount of work in reconstructing my own board and my own cabinet.”

“How successful will we be?” asked Nair. “The next couple of years are going to be interesting in higher education anyway, and hard. All presidents will probably face more pressures, more criticism. We’ll see if the institutions that have the courage to make these hires are also investing in supporting these people when times get hard.”