You have /5 articles left.

Sign up for a free account or log in.

This year’s ‘JBHE’ survey found that many high-ranking liberal arts colleges made substantial year-on-year gains in enrolling first-year Black students.

iStock/Getty Images Plus

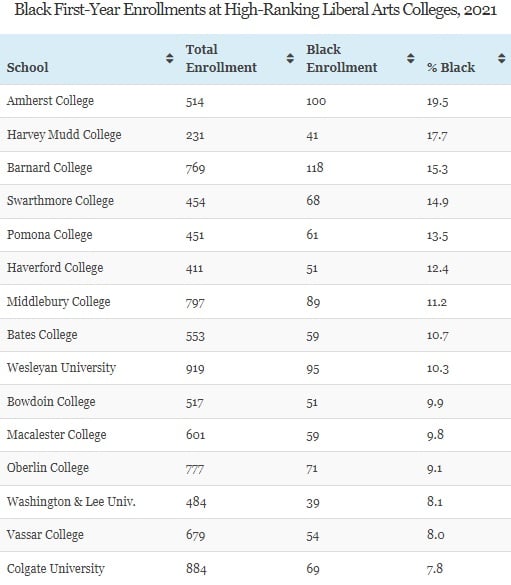

The Journal of Blacks in Higher Education has tracked first-year Black students’ admissions to the same 30 high-ranking liberal arts colleges for the past 28 years, with Amherst College reporting the highest percentage for 13 of those years—including this one. For the 2021–22 academic year, Amherst broke its own previous record by enrolling 100 Black students in an entering class of 514, which amounts to 19.5 percent.

It’s no accident—Amherst has made a concerted effort to attract nonwhite students, including by spending $61 million on financial aid last year, with the average student grant equaling $50,000.

This year’s JBHE survey found that many other high-ranking liberal arts colleges also made substantial year-on-year gains in enrolling Black first-year students, though some of those increases may reflect a change in counting methodology as much as an actual spike in numbers. Due to a recent change, some colleges followed the Department of Education’s classification guidelines, which separate Black students from multiracial and biracial students and don’t include Black international students. By contrast, JBHE guidelines, which some institutions adopted this year, count as Black any student that identifies as being of African descent.

Robert Bruce Slater, managing editor of JBHE, urged caution in interpreting the survey data for another reason.

“Some of our numbers on the increase in Black students from 2020 to last year are really huge, but I think that’s basically just due to the pandemic,” he said.

Slater said this year’s data were “weird” because enrollment dropped during the COVID-19 pandemic, so what looks like a big increase for 2021 may actually be just a rebound from the dip. He added that first-year Black enrollment could also be inflated this year because so many high school graduates opted to delay college by a year.

Still, Slater said this year’s report shows the vast majority of leading liberal arts colleges have made “huge progress” in admitting Black students over the last 10 to 15 years.

“Most, if not all, of the leading liberal arts colleges are sincerely trying to boost their diversity numbers of their student bodies,” Slater said. “And that’s a good thing. Twenty years ago, that probably wasn’t the case.”

Harvey Mudd College in California ranked right behind Amherst in the percentage of first-year Black students entering in the fall, with 17.7 percent, or 41 out of 231 students. In 2020, the entering class was 8.6 percent Black. And back in 2009, the college ranked dead last in the JBHE survey, with just three Black first-year students, or 1.4 percent of the entering class.

Harvey Mudd’s increase is especially notable, the JBHE report says, because it’s a liberal arts college with a heavy emphasis on math, science and engineering.

“The fact that Harvey Mudd tends to concentrate on STEM majors, where traditionally a lot of Black students have not gotten into, and the fact that they’re able to attract such a large incoming class of Black students, is a credit to their efforts to increase their diversity,” Slater said.

Thyra Briggs, vice president of admission and financial aid at Harvey Mudd, said the pandemic actually helped the college boost minority student enrollment through its Future Achievers in Science and Technology (FAST) program, which seeks out students whose identities are underrepresented in STEM.

Before the pandemic, the program would pay for about 80 high school seniors to fly out to Harvey Mudd to decide whether they wanted to apply, Briggs said. But by making the program virtual during the pandemic, the college allowed 200 prospective applicants to participate.

As a result, applications from Black students increased by 79 percent, and those from Hispanic and Latinx students increased by 49 percent, Briggs said.

Briggs said another reason for the increase in first-year Black student enrollment could be the college’s decision not to require SAT or ACT scores for the entering Classes of 2021, 2022 and 2023. However, as a STEM-focused institution, the college still mandates that incoming students complete a year each of physics, chemistry and calculus in high school, which can pose a challenge to recruiting diverse students.

“We know just based on this systemic inequality, and inequity in education, that it’s much more likely that the Black and brown students are the last group to have access to some of these classes,” Briggs said. “And so I think that’s one of the things that has been a barrier for us, and of course, the SATs have certainly been a barrier.”

Barnard College in New York ranked third in the percentage of Black first-year students in this year’s survey. The women’s college has 118 first-year Black students, which is 15.3 percent of its entering class of 769 students. Compared with last year, Barnard saw an increase of 57.3 percent.

Jennifer Fondiller, vice president for enrollment and communications, credited Barnard Bound, the college’s three-day virtual program that invites current high school seniors of color to meet campus community members and participate in admission workshops, with the goal of facilitating their applications.

The college also works to diversify recruitment by partnering with community-based national and local organizations like Minds Matter, an academic and mentoring program for New York City high school students, and the Schuler Scholar program, a nonprofit that helps first-generation students, students of color and low-income students in Chicago and Milwaukee attend highly selective colleges.

“Having a diverse student body is an important part of our mission, and we showcase our commitment to this by integrating it as a key priority across all of our various initiatives and programs,” Fondiller said.

Swarthmore College in Pennsylvania ranked fourth in the survey, with 68 Black first-year students, which is 14.9 percent of the college’s entering class of 454. The JBHE report states that this is the sixth year that Swarthmore ranked in the survey’s top five. Swarthmore saw a 25.9 percent increase in Black first-year student enrollment over last year.

“We all benefit from an intentionally small living and learning environment with an ever-growing diverse population of students, and that diversity leads to a richer educational experience for all students and members of our community,” said Alisa Giardinelli, assistant vice president of communications of Swarthmore.

Giardinelli pointed to the college’s need-blind admissions policy, which allows it to disregard a student’s ability to pay when evaluating each application. She also said the college saw a higher application and yield rate of low-income and underrepresented students as a result of Swarthmore’s fly-in program, which invites a few hundred students on an all-expenses-paid trip to explore life at Swarthmore.

Middlebury College in Vermont enrolled 89 Black first-year students, who make up 11.2 percent of its entering class. That’s a 58.9 percent increase from last year’s entering class, which had 56 Black students.

Nicole Curvin, Middlebury’s dean of admissions, pointed to the college’s change in testing requirements, which made the SAT and ACT optional as part of a three-year pilot through the 2022–23 application cycle. She said the college’s Student Ambassadors Program also helps the admissions office recruit students from rural, low-income or multiethnic areas who might not know about the college. The program deploys Middlebury students home on break to connect with prospective students in their areas.

“While we value our recent enrollment successes, it is clear that there is more work to do to share the value of a liberal arts and sciences education with an even broader group of students from diverse backgrounds,” Curvin said. “To achieve a more equitable admissions process, we are working to clear away obstacles, including standardized tests, and to identify barriers that might prevent talented students from considering and applying to Middlebury.”

Other efforts at Middlebury include partnerships with the Posse Foundation, a national nonprofit organization that provides scholarships for groups of diverse students from over 20 cities to attend 64 partner institutions, and QuestBridge, a national nonprofit that connects low-income and first-generation students with different institutions. Curvin also pointed to the college’s Discover Middlebury program, which is a free fly-in program held every October for underserved students to interact with campus community members.

While the enrollment increases among Black first-year liberal arts students represent a positive trend, challenges remain, said Will Patch, senior enrollment insights leader at Niche, a company that surveys students on enrollment and admissions. Over the past few years, more Black students headed to college have indicated they’re applying for scholarships, Patch said, but Niche also found that Black students were more likely to rule out colleges based on the “sticker price” of the institution, or the cost before financial aid. Many of the liberal arts colleges in the JBHE report have high tuition and room and board rates; Amherst College, for instance, costs $79,600 without aid.

“For the Class of 2022, 72 percent of Black students said that they ruled out colleges based on the sticker price,” Patch said. “Well, for these colleges on that list, you’re ruling out a lot of potential students.”

He added that while some liberal art colleges have hefty endowments and can cover a lot of a student’s costs with financial aid, high school students don’t necessarily know that’s an option for them.

“Colleges can keep talking about how generous their financial aid is, but that sticker price is turning off a lot of students,” Patch said. “So colleges need to be thinking about how do we address that earlier and how do we talk about these scholarship opportunities? And how do we get the middle schoolers, the freshmen, the sophomores, the parents, to let them know early that, yes, we may have a high sticker price, but here’s how we’re going to make it work.”