You have /5 articles left.

Sign up for a free account or log in.

PEN America tracks and opposes new state bills and laws targeting so-called divisive concepts.

PEN America

The recent wave of educational “gag orders” restricting the teaching of race, gender or other so-called divisive concepts is a dire threat to what makes American higher education unique and sought after. Such legislation is a far greater threat to free speech than any problem it might be trying to solve, and it also risks colleges’ and universities’ accreditation. Institutions must speak out against this kind of government censorship, which is not politics as usual.

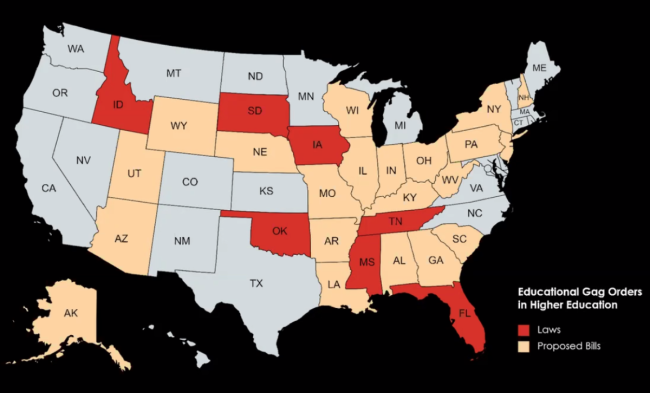

These were the major themes that emerged during a Wednesday panel organized by the free expression group PEN America and the American Association of Colleges and Universities. The occasion was the release of a new joint statement from the two groups opposing legislative restrictions on teaching and learning, which notes that 70 such bills affecting higher education have been introduced in 28 states, and passed in seven states, since January of last year. (More states have passed bills affecting K-12 education.)

“These legislative restrictions infringe upon freedom of speech and academic freedom, constraining vital societal discourse on pressing questions relating to American history, society and culture,” the joint statement says. “Legislative restrictions on freedom of inquiry and expression violate the institutional autonomy on which the quality and integrity of our system of higher education depends. In the U.S., the content of what is taught and discussed in higher education classrooms is shielded from direct governmental control.”

This isn’t the first time these groups, or others, have publicly opposed educational gag orders (PEN, in particular, has an ongoing legislation tracking project and regularly speaks out). But the joint statement expresses new “alarm” at the advancing trend toward censorship—as did panelists in their comments.

Suzanne Nossel, CEO of PEN, said that her organization has for years worked to “articulate how we believe that the drive for a more equal and inclusive campus and society cannot, must not, need not come at the expense of robust protections for free speech and academic freedom. And what we’ve seen over the last year and change is just this startling and fierce backlash against what is seen as a kind of orthodoxy emanating from the left.”

Nossel and others on the panel agreed that higher education must grapple with the speech climate with respect to what’s been called campus “illiberalism” or, more pejoratively, the “snowflake” problem. But all panelists were in full agreement that legislating what can and cannot be discussed on college campuses is not the answer.

Said Nossel, “As a free speech defense organization, we recognize not all threats to free speech are created equal. If you’re going to make a hierarchy of which ones ought to be most concerning, it’s the ones that go directly to what our First Amendment protects against, which is intrusions on and impairments on freedom of speech emanating from the government.”

Regarding critical race theory, gender and other concepts that this legislation targets, Nossel said, “It’s a very specific perspective that’s being called out and made illegal. This is an affront to open discourse, to the values that we stand for as an organization. For me personally, I find this, as an American, something I never expected to see or witness in my own country. And I think it’s extremely important to point this out this is not just part of the culture war. This is not just a tussle of sorts between the right and the left. This is a real turning of the backs of our governors and legislatures away from fundamental constitutional principles.”

‘A Clear, Unambiguous Voice’

Panelist Eduardo Ochoa, president of California State University, Monterey Bay, said, “It’s critical for us to speak with a loud voice, a clear, unambiguous voice on this issue. As my colleagues have pointed out, this is a fundamental aspect of strength of American higher education—indeed, of American democracy. The ability to express your views regardless of whether they’re popular or whether they meet the orthodoxy of the established power is critical to the strength and the flexibility of this nation.”

Of college and university leaders, Ochoa said “this is something that’s a real easy issue for presidents to be on the side of the angels about.”

Not all presidents have openly opposed such legislation, however. Kent Fuchs, president of the University of Florida, for instance, recently told faculty members not to violate a new state law that he said governs “instructional topics and practices.” The law, known as HB 7, is better known among its supporters as the Stop the Wrongs to Our Kids and Employees (WOKE) Act, which Republican governor Ron DeSantis introduced in December as a bulwark against the “state-sanctioned racism that is critical race theory.” Faculty members were also warned that running afoul of this new law could result in "large financial penalties" for the university, based a separate new law enforcing HB 7.

Panelist Ronald Crutcher, president emeritus of both the University of Richmond and Wheaton College of Massachusetts, said that while some politically motivated actors, including those in the news media, “try to position universities as these places where professors are trying to poison the minds of young people,” higher education leaders must use “real stories of students and student voices representing a broad swath of perspectives to help people understand what’s really going on on our campuses.”

Jeremy Young, senior manager of free expression and education at PEN, said that these divisive concept bans don’t even appear to reflect broad public opinion, citing a 2020 poll by the American Historical Association finding that 77 percent of Americans (and 74 percent of Republicans) say it’s acceptable to teach about the harm some people have done to others, even if that subject matter causes learners discomfort. And while some bills and laws don’t explicitly implicate college teaching, he said, their effect in certain states has chilled administrators into changing the curriculum anyway.

The specificity of these laws varies, but threatened speech ranges from historical content about racism and slavery to student organizations that represent gender or racial identities, Young also said.

Undermining U.S. Higher Ed

Addressing how the recent divisive concepts bans are part of an even larger trend toward legislators and other figures interfering in long-held higher education norms, Lynn Pasquerella, president of the AAC&U, said, “There’s certainly a growing sense of urgency around responding to and indeed redressing the overreach on the part of legislators, governors and state governing boards into curricula, hiring, tenure and promotion decisions and accreditation, alongside the monitoring of faculty and student perspectives and viewpoints that threaten to undermine academic freedom and shared governance on college and university campuses.” (Some recent examples: Florida introduced a mandatory survey on the climate for college viewpoint diversity and passed a post-tenure review law, the University System of Georiga made it possible to fire tenured faculty members without clear faculty input, and Mississippi’s Board of Trustees of State Institutions of Higher Learning changed how faculty members get and maintain tenure in near secrecy.)

What’s special about the joint statement, Pasquerella continued, is that it “highlights the distinctiveness of the American higher education system, whose strength is derived from its independence from direct governmental control, and it showcases the ways in which America’s global leadership in higher education is grounded in colleges and universities being self-governed and self-regulated through accreditation processes that are designed to ensure academic quality and integrity, as well as freedom from undue political influence.”

Per Pasquerella’s point, the statement says that colleges and universities “are self-governed and self-regulated according to widely accepted principles that are safeguarded by a well-established network of seven regional accreditation agencies.”

Not mentioning by name but certainly evoking yet another new Florida law requiring colleges and universities to change accreditors and to sue those accreditors whose oversight they don’t like, the statement says that accreditors “monitor institutions’ adherence to a series of self-governance principles, including freedom from undue political influence” and that colleges and universities “forced to comply with political edicts governing curricula and classroom discussions may forfeit their eligibility for accreditation, a drastic result that could compromise students’ eligibility for federal financial aid and place the institutions themselves in jeopardy.”

Educational gag orders imperil shared governance, the statement also says, as the “imposition of political restrictions on college and university curricula usurps and unduly constrains this faculty prerogative, substituting ideologically motivated government dictates for subject matter expertise and undermining the integrity of the academic enterprise.”

On academic freedom, the statement says that in “teaching and learning, as in scholarship and research, the freedom to engage in intellectual debate, and to share ideas and raise questions without fear of retribution or censorship, expands the boundaries of knowledge and drives innovation.”

An effort to curb this process therefore “undermines our society’s democratic future.”

The Way Forward

Asked during the event how colleges and universities might address outstanding concerns about illiberalism in the classroom speech environment on their own, Ochoa said they can promote effective teaching, versus “preaching,” along with critical thinking. Crutcher suggested the Bipartisan Policy Center’s campus free speech “roadmap” report, which he helped write. PEN has a separate report on classroom free expression in a “divided America.”

The University of California National Center for Free Speech and Civic Engagement offers resources, as well, including a newly released paper by one of its fellows, Lynn Comella, on best practices for navigating campus controversies. Michelle Deutchman, center director, was not involved in the new joint statement or panel, but she said Wednesday that there are a "number of things that universities can do, and some of them require going back to basics—education for students, staff and faculty about the First Amendment; discussion about why there is value in protecting offensive and ugly speech; formal guidance for graduate teaching assistants on how to facilitate challenging conversations in the classroom; and training about the distinction between academic freedom and free speech and why that matters. These things are essential in building a foundation that sustains open discourse and free inquiry.”

Deutchman “absolutely” agreed with the new joint statement itself.

“Legislative encroachment on university autonomy is one of the greatest threats to expression and academic freedom," she said. "When the government attempts to determine what can or should be taught in our nation’s classrooms, it undermines the principles upon which higher education depends—the unbounded pursuit of knowledge and the unfettered exchange of ideas. This, in turn, shakes the foundations of our democracy.”