You have /5 articles left.

Sign up for a free account or log in.

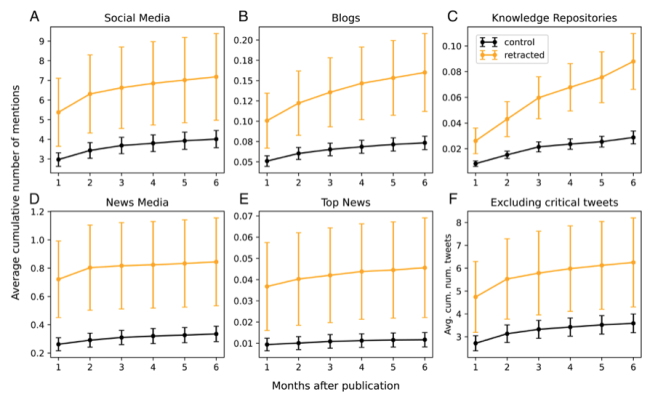

After publication and before retraction mentions and average cumulative number of mentions received within six months after publication on four types of platforms and in top news outlets for both retracted and control papers.

PNAS

Retraction is not effective in reducing online attention to problematic research papers, according to a new study in Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (PNAS).

The study doesn’t support the idea that retraction risks the Streisand effect, or that it inadvertently amplifies bad research. Instead, the study demonstrates the limits of what retraction can do in terms of curbing the spread of poor science.

Most significantly, the study found that by the time a problematic paper is retracted, public attention has been reduced to a relative trickle, and focuses on the retraction incident itself, not the research in question. (Retraction timelines vary widely, but they generally take months or years, even when the early evidence for retraction is compelling.)

“Retractions come too late to intervene in uncritical mentions of problematic papers,” said co-author Emőke-Ágnes Horvát, an assistant professor of communication at Northwestern University. “By the time the retraction notice is issued, there are either hardly any mentions of the paper or the mentions are overwhelmingly criticizing the paper.”

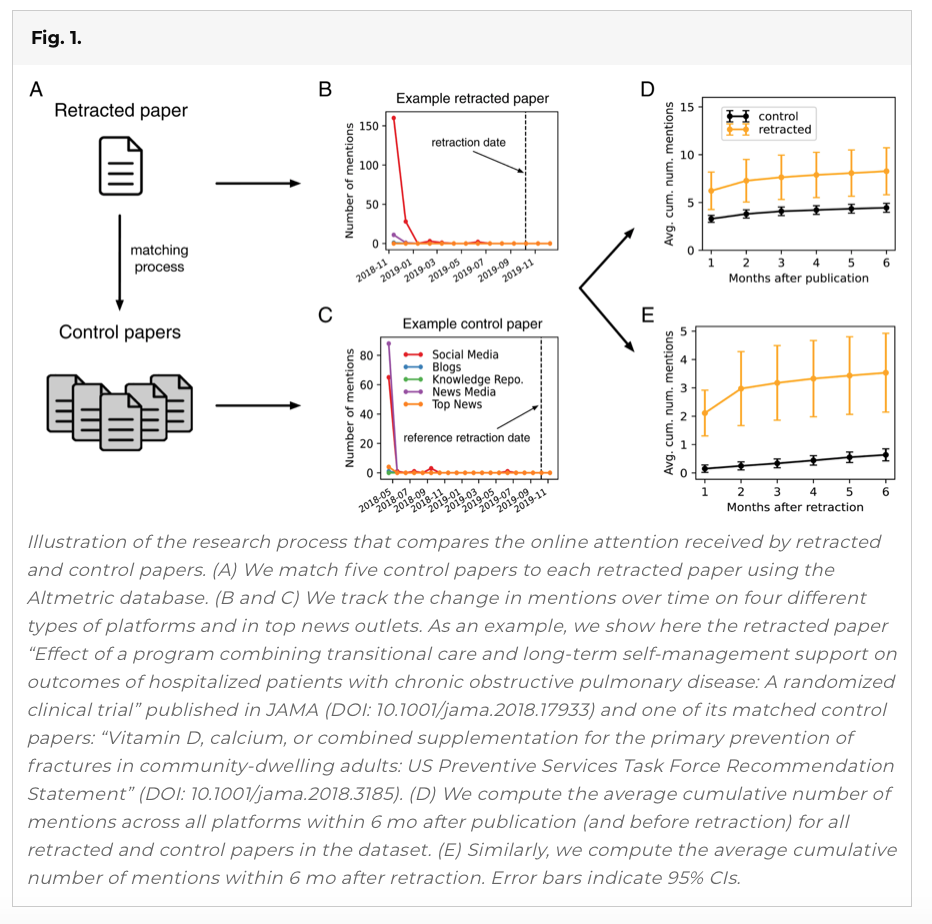

Co-author Daniel Romero, associate professor of information at the University of Michigan, underscored that the study did not analyze attention to retractions, just attention to articles after publication and soon before and after retraction. And a key point is that retracted papers receive more uncritical attention before they’re retracted than comparable unretracted papers, across platforms, he said.

Co-author Daniel Romero, associate professor of information at the University of Michigan, underscored that the study did not analyze attention to retractions, just attention to articles after publication and soon before and after retraction. And a key point is that retracted papers receive more uncritical attention before they’re retracted than comparable unretracted papers, across platforms, he said.

That said, retracted papers also receive relatively more critical mentions (negative attention) on social media ahead of retraction, suggesting that social media users are able to identify problems with them.

Implications for Public Discourse

Crucially, this new paper does not look at academic citations, only attention to research on social media (Facebook, Reddit, Twitter and more) and on “highly curated” platforms such as news websites, Wikipedia and other repositories and research blogs. (Previous studies have shown that retracted research continues to be cited, in many cases because retractions go unnoticed.)

Of course, many academics use social media, so they are generating some of the attention the study addresses. But in focusing on platforms for the public, the study has implications for important social debates that may be influenced by misinformation.

Most retracted papers don’t get much attention, good or bad, but some do get visibility that extends across social media, news, knowledge repositories and blogs, Horvát said. Retracted research linking childhood vaccines to autism, for example, or more recently retracted COVID-19–related papers suggest that “the harms of highly shared problematic research can be substantial,” she added.

Critical and Uncritical Attention

Using Retraction Watch’s database of retracted papers, Horvát, Romero and a third co-author, Hao Peng, analyzed the amount and type of attention (“critical” or not) that 3,851 retracted papers from the last 10 years received. Then they looked at attention to unretracted papers from the same journals, published around the same time, with the same number of authors and author research impact, to compare.

As for how much attention eventually retracted papers get upon publication, the study found that across 2,830 retracted and 13,599 control papers with a tracking window of at least six months, the retracted papers received more attention after publication on all types of platforms studied. On average, papers obtained mentions most frequently on social media, followed by news media. They received roughly similar amounts of attention on blogs and knowledge repositories. (The researchers tracked attention levels via Altmetric, which follows the spread of scholarly content online.)

Across different types of platforms, retracted papers were not discussed significantly more often than control papers immediately before their retraction, according to the study. Some 94 percent of them received no mentions in the last month before retraction.

Twitter accounted for 80 percent of mentions in Altmetric. Compared with control papers, the eventually retracted papers received a higher fraction of critical tweets, suggesting that Twitter may be an effective tool for highlighting troublesome research.

Ivan Oransky, co-founder of Retraction Watch, said Wednesday that “it makes complete sense that the papers that ended up getting retracted have had more attention, in general.” Prior research has shown that retractions occur most frequently among highly cited articles published in high-impact journals, he said (this is also mentioned in the paper), and his experience over 12 years at Retraction Watch “is that that the best predictor of whether a paper will be retracted is how much attention it gets.”

Oransky said a corollary to the new paper's findings is that “journals and peer reviewers really aren’t doing a great job of ferreting out the problems that they should be ferreting out.” He added, “It’s another reminder that prepublication peer review is wholly inadequate. And I would argue it’s getting worse, because there’s so many papers that need to be peer reviewed, and not enough peer reviewers.” (Oransky also said he’s concerned about how and to what extent journals explain why a paper has been retracted.)

It’s true that publication volumes keep increasing, and many peer reviewers are declining referee requests due to burnout and other issues. Regarding the peer-review crisis, James Stacey Taylor, associate professor of philosophy at the College of New Jersey, proposed an unusual solution in his recently published book, Markets With Limits: How the Commodification of Academia Derails Debate (Routledge): require authors to pay journal referees a “bounty” for each error they detect in the manuscripts they’re reviewing, whether or not the paper gets accepted for publication.

“Maybe as little as $10 for a bibliographic error, to, say, $100 for a source that has been misrepresented,” Taylor explained. “Of course, researchers could reduce their liability to zero simply by being very careful.”

Asking academics to be bounty "hunters" is "unlikely to eliminate error, but it will definitely reduce it,” Taylor said of the idea, which is sure to be controversial, given that the idea of paying reviewers in any way remains controversial.

Of the PNAS paper, Taylor said that he’d be interested to know more about papers pulled for plagiarism versus falsified research results, with the latter arguably having a bigger tendency to “pollute” public debate (the causes of retraction have been studied elsewhere, but not quite in relation to the amount of attention these papers get).

Beyond that, Taylor said he remained unsure that such "online sources with their shelf lives are really what we should be concerned about.” Retractions—when noticed—do effectively serve their purpose in academic discussions, he added.