You have /5 articles left.

Sign up for a free account or log in.

Piedmont president James Mellichamp will retire after a semester of layoffs and public resignations capped a 10-year tenure marked by institutional growth as well as controversy and financial woes.

Courtesy of NowHabersham.com

On Monday, after a special meeting of the Board of Trustees, Piedmont University president James Mellichamp announced that he would retire once a successor is named. A few days later, his husband, Daniel Smith, resigned from his position as senior projects manager at the university.

It was the culmination of a tough semester for Piedmont. Two rounds of unexpected budget cuts, faculty layoffs, a vote of no confidence, professors’ contracts hanging in limbo and high-profile resignations from Provost Daniel Silber and endowed professor Carson Webb left the private college in Demorest, Ga., reeling with uncertainty and frustration.

Some faculty members left to avoid the possibility of being unceremoniously let go.

“The vibrations for the past several months have been very negative,” said Dale Van Cantfort, a communications professor and chair of Piedmont’s Faculty Senate. “I came to work every day trying to figure out who was the next person that was going to call me to tell me they weren’t coming back next year.”

Much of the blame for the chaos fell on Mellichamp. Faculty called for his resignation and even asked the Board of Trustees to suspend him and Smith from campus, citing concerns about their conduct and alleging retaliatory and even abusive behavior. After Monday’s announcement, the faculty issued a statement asking for Mellichamp’s immediate retirement or removal and requesting an interim president to serve during the search for a permanent replacement.

Much of the blame for the chaos fell on Mellichamp. Faculty called for his resignation and even asked the Board of Trustees to suspend him and Smith from campus, citing concerns about their conduct and alleging retaliatory and even abusive behavior. After Monday’s announcement, the faculty issued a statement asking for Mellichamp’s immediate retirement or removal and requesting an interim president to serve during the search for a permanent replacement.

“Immediately after the announcement, a number of faculty reached out to me to say they were scared that this would lead to further retaliation [for criticism of Mellichamp], because there was nothing to hold him not to do it anymore,” Cantfort said.

But Cantfort said he’s since had productive discussions with both Mellichamp and the Board of Trustees, who have assured him that no retaliatory actions will take place and that the search process will “move swiftly.”

That process has already begun. On Tuesday the university launched its presidential search, appointing Barbara Strain, a lifelong local resident and a relatively new member of the Board of Trustees, as chair of the committee.

“I am committed to a prompt, collaborative, transparent search,” Strain wrote in a statement. “It is vital that we hire a president who can continue Piedmont’s growth and success.”

Neither Mellichamp’s office nor a representative for the university responded to multiple requests for comment.

Cantfort said Mellichamp’s departure is only “a first step” in resolving Piedmont’s financial and administrative problems.

“There is more that needs to be done,” he said. “First and foremost, we need an effective leader to help us work together to find those solutions.”

‘No Moral Choice but to Leave’

The spring semester at Piedmont started out on a relatively good note: President Mellichamp had assured faculty at an all-hands meeting last November that the university’s finances were under control, and faculty had even received a 5 percent raise.

In February, it became clear that there was financial trouble lurking behind the university’s optimistic veneer. Mellichamp announced a first round of budget cuts, which included 22 staff and eight faculty layoffs. Faculty were assured that would be the end of it.

In early June, though, a second round of budget cuts was announced, which originally included 15 additional faculty layoffs. The number of faculty cuts was eventually reduced to four after negotiations with the Board of Trustees, but the move incensed faculty and administrators alike—including the provost, Silber.

Shortly afterward, Silber resigned in protest over the “unethical” budget cuts, writing in an email to colleagues that he had “no moral choice but to leave.”

Webb, who had been the Harry R. Butman Professor of Religion and Philosophy at Piedmont since 2017, resigned June 14. Like Silber, he outlined his reasoning in a blistering email to colleagues, calling out Mellichamp and other administrators for “underhanded,” “embarrassing” and “unethical” behavior, including intimidation and “workplace bullying” in the wake of Silber’s resignation.

“The endowed Harry R. Butman Chair of Religion and Philosophy was established in order to honor the legacy of the Rev. Dr. Butman and the commitment to ethics that plays such a key role in Piedmont’s Congregationalist heritage,” Webb wrote. “Unfortunately, Piedmont’s current leadership (and I use that term loosely) has dishonored this legacy to such an extent that I can no longer in good conscience be a part of it.”

Webb took a break from packing up his home to tell Inside Higher Ed that while the decision to leave Piedmont was difficult for him and his family, he believes it was the only moral choice considering the university’s actions.

“I am very sad to leave Piedmont. I think it’s a very special institution … and I’m also deeply saddened to be leaving this area. My family and I really settled down here,” said Webb, who has three young children. “At the same time, I think I made a good decision.”

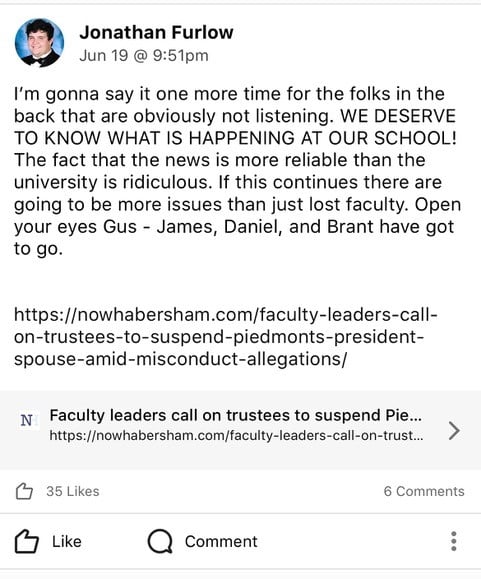

Students were not naïve about the tension simmering on campus over the past few months. Jonathan Furlow, a rising senior studying theater and accounting, had been very happy with his time at Piedmont. In early May, he was interviewed for the university’s alumni news outlet, where he extolled his education and praised his professors.

“Piedmont is a place where you can make your college experience your own,” he said. “I’m getting the education that’s right for me.”

But the events of the past few months raised concerns about Piedmont’s stability, and the abrupt faculty layoffs in May made Furlow wonder what other problems were hidden behind the university’s optimistic messaging.

“The feeling on campus was, if they’re not telling us this, what else aren’t they telling us?” he said. “It’s been very odd and heartbreaking to look back at the school I go to and see that it isn’t the same place I walked into three and a half years ago. This is an entirely new mess.”

Furlow said that when Silber resigned, the anxiety on campus reached a fever pitch.

“That’s when a lot of us looked around and said, ‘OK, should I transfer?’” he said.

On Sunday, the day before Mellichamp announced his retirement, Furlow took to Piedmont’s internal social media app to call for the resignation of three administrators: Mellichamp, Smith and Piedmont’s chief financial officer, Brant Wright.

“WE DESERVE TO KNOW WHAT IS HAPPENING AT OUR SCHOOL!” Furlow wrote in the post, which had 35 likes when Inside Higher Ed obtained a screenshot of it. “If this continues, there are going to be more issues than just lost faculty.”

One professor and department chair, who spoke on the condition of anonymity out of concern about retaliation, said that Piedmont’s descent into twin fiscal and confidence crises over the past year was upsetting to them and others who believe in the university’s mission.

“Piedmont really is a great institution, and a great place for students to go,” they said. “But the administration has just really torn it to shreds.”

A President’s Mixed Legacy

Mellichamp will leave Piedmont after 40 years at the university and a decade as president. Under his leadership, Piedmont’s residential student population grew by 60 percent, and he has led multiple successful capital campaigns, including one for the creation of a $10 million conservatory of music—a project of personal significance to Mellichamp, who made his name as a concert organist.

But Mellichamp’s legacy is also marred by conflicts with faculty, including legal battles; allegations of professional and sexual misconduct; and, most recently, fallout from the university’s sudden financial troubles and subsequent budget cuts.

Mellichamp has been at the center of multiple court cases that have drawn unwanted attention to Piedmont and sapped money from the institution for legal fees.

In 2018, former Piedmont biology professor Robert Wainberg, who had been tenured before the university ended its tenure program in 2004, filed a wrongful termination lawsuit against Mellichamp.

In 2021, another former biology professor, Rick Austin, who was also serving as Demorest’s mayor at the time, filed his own lawsuit against Mellichamp. He had submitted an affidavit in support of Wainberg’s wrongful termination suit, and he claimed he was fired in retaliation for supporting his colleague. In his affidavit Austin claimed, among other things, that Mellichamp groped him while he was a professor there and failed to intervene when an inappropriate professor-student relationship was reported.

Piedmont, on the other hand, had filed a lawsuit against the city of Demorest the year before, accusing the city, under Austin’s leadership, of committing fraud, conspiracy and theft by extortion by targeting the college with a water and sewage price hike, among other allegations.

Austin did not respond to Inside Higher Ed’s attempts to reach him for comment.

Austin’s lawsuit against Mellichamp was settled out of court for an undisclosed amount. Wainberg’s suit against Mellichamp is ongoing, as is the case the university launched against the city of Demorest. Representatives from Piedmont did not respond when asked whether the university would continue footing Mellichamp’s defense bills after his retirement or whether the university would drop the case against the city.

“President Mellichamp has done some good things for this institution, but his biggest problem has always been his narcissism,” said the department chair. “That, I think, was ultimately his downfall.”

Another Shoe to Drop?

Both Silber’s and Webb’s resignation letters call attention to the “unethical” behavior and “egregious” financial mismanagement of Brant Wright, Piedmont’s senior vice president for administration and finance.

“No problems at Piedmont will be fixed until Brant Wright is gone,” the department chair said.

According to Piedmont’s federally filed 990 tax forms, the university posted a $2.9 million surplus in fiscal year 2019. But in FY 2020, Wright’s first full year on the job, Piedmont reported a $1.6 million deficit.

Mellichamp pinned Piedmont’s budget shortfalls, which weren’t communicated to faculty until last fall, on the pandemic. But enrollment at the tuition-dependent institution did not decline significantly from 2019 to 2020, according to data from the National Center for Education Statistics. Wright then recommended and oversaw the budget cuts that led to 12 faculty layoffs and Silber’s resignation.

It wasn’t the first time Wright has presided over a budget shortfall and faced backlash for recommending layoffs as a solution. In 2019, Wright recommended departmental cuts and 10 faculty layoffs at Montana Tech, where he was serving his final year as vice chancellor of finance and administration before moving to Piedmont. After public backlash to the proposed cuts, Wright’s financial oversight responsibilities were reassigned, according to reporting by The Montana Standard.

Wright did not respond to multiple requests for comment.

A New Hope

Furlow said the prospect of new leadership at Piedmont makes him much more optimistic about the university’s future.

“If we can get a new president, a new provost and hopefully a new finance vice president, I think everything at Piedmont will be back on track,” he said.

Cantfort said news of Mellichamp’s retirement led to a veritable “vibe shift” at Piedmont.

“Just in the past 24 hours, among those faculty and staff on campus this summer, I’m seeing smiling faces where I didn’t before. I’m seeing people say hello whereas before they’d just walk with their heads down,” he said Tuesday, a day after Mellichamp’s announcement.

Faculty who will be returning in the fall also received their contracts in the mail this week—two months later than they have in past years, but better late than never, said the department chair.

“People are hopeful,” Cantfort said. “The impression is that this is the start of a new day.”