You have /5 articles left.

Sign up for a free account or log in.

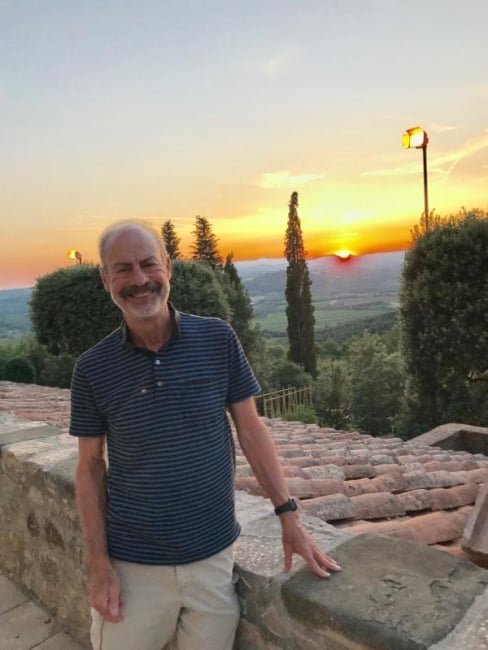

Retired NYU administrator and novelist Robert Berne in Montalcino, Italy, about 10 miles from where Berne says he envisioned his fictional village of Follamento.

Courtesy of Robert Berne

“I did everything right as a university administrator, so how did I end up in this Panamanian jail cell?”

That sentence had been swirling around Robert Berne's head for 10 years while he served as New York University’s executive vice president for health. It sparked his desire to try his hand at fiction—and, after he retired in 2017, it became the first sentence of his debut novel, Tuscan Son (Moonshine Cove Publishing, 2022).

Berne, who worked at NYU for 41 years, including 15 as a vice president, told Inside Higher Ed that the novel was inspired by his time as an administrator. Though he’s never been to prison, he and his protagonist have plenty of other things in common: both served as vice presidents at private Manhattan universities, both spent time in Italy negotiating with dead donors’ unhappy children over a large gift of property and both have a lot to say about the politics and bureaucracy of higher education administration.

“My goal was to tell some interesting things about university life, but I decided I didn’t want to write a nonfiction memoir and I didn’t want to write ‘The Seven Things I Learned as a University Administrator,’ because I never read those things,” Berne said. “So I thought turning it into a novel was the best way to do it.”

“My goal was to tell some interesting things about university life, but I decided I didn’t want to write a nonfiction memoir and I didn’t want to write ‘The Seven Things I Learned as a University Administrator,’ because I never read those things,” Berne said. “So I thought turning it into a novel was the best way to do it.”

The novel follows Bill, the senior vice president for academic initiatives at the fictional Olmsted University—Berne’s proxy for NYU—as he helps iron out the terms of a generous donation bequeathed by a wealthy Italian alumnus. As the story progresses, Bill’s path to the jail cell in Panama is slowly revealed as he travels through the Tuscan countryside and comes into possession of a dangerous secret.

Structured as a series of journal entries written by the narrator in jail, Tuscan Son intercuts descriptions of life in the Panamanian prison with wryly recounted vignettes and observations about his job at Olmsted. On one page the narrator is discussing the frustrating ubiquity of faculty committees; on the next he’s being shaken down for cigarettes in the prison yard. Berne evokes a student protest in the university president’s office with the same kind of intrigue he uses to describe the drug-family turf war Bill gets caught up in.

“There were intentional parallels drawn between doing business in the prison and doing business in a university,” he said. “You’re trying to gain support and constituencies who will favor what you want to do.”

Many of the characters and circumstances in Tuscan Son would be familiar to anyone in higher education: an overwhelmed and embattled president trying to please everyone; a bevy of righteous student activists issuing demands for fossil fuel divestment; and a squabbling university working group trying, and largely failing, to reach a compromise.

“As an administrator, sometimes it is anarchy, while to many faculty, it is a corporate behemoth,” Bill writes of Olmsted in the novel. “As quirky as Olmsted seems now, it is normal compared with being in a Panamanian prison.”

Based On a True Story

Tuscan Son kicks off with an Italian alumnus donating an entire Tuscan village to Olmsted to serve as the hub for a study abroad program. After much infighting among faculty department chairs and deans, Bill, Olmsted’s resident “academic troubleshooter,” is sent to Italy to negotiate the terms of the bequest with the donor’s lawyer and deal with the attempts of the donor’s angry heir to wrench back control of the property.

The descriptions of the Tuscan hills and ancient villages are informed by the time Berne and his wife have spent in the area, one of their favorite vacation destinations. But Berne said he has also dealt with a very similar donor situation, in the same region of Italy.

In 1994, NYU was bequeathed a Renaissance villa in Tuscany by the Anglo-Italian writer Harold Acton, who is said to have inspired the character Anthony Blance in Evelyn Waugh’s famous novel Brideshead Revisited. The villa now serves as the headquarters of NYU’s study abroad program in Florence.

But just like the bequest in the novel, the real-life gift came with headaches for NYU. Since it received the villa 28 years ago, the university has been locked in a legal battle with the other heirs of

“That really gave me a sense of Italy, a sense of how business is done there and a sense of how universities from the States could interact with Italy,” Berne said.

In Tuscan Son, Bill is sent to the village, Follamento, essentially as a diplomat and negotiator (and, later, as a kind of private detective). Berne said that dealing with donor disputes and stipulations is both a frustrating and rewarding part of a university administrator’s job.

“A donor and a university will spend a lot of time negotiating the terms of a gift,” he said. “You don’t find donors who say, ‘Here’s $100 million; give it your best shot.’ Instead, the donors want to foster art, solve poverty, eliminate injustice … that makes it fun but challenging.”

Olmsted’s president articulates this frustration concisely in Tuscan Son. “Why don’t donors give their money for what we want to do?” she says.

The Campus Novel, From an Administrator’s Viewpoint

There have been hundreds of novels written about campus life and academia, most of them told from the perspective of students—Donna Tartt’s The Secret History, John Williams’s Stoner—or faculty, such as Vladimir Nabokov’s Pnin and Don DeLillo’s White Noise. But novels focused on college administrators are rare. Jean Hanff Korelitz’s The Devil and Webster, about the first female president of a fictional New England college, is one of very few titles that Tuscan Son can count among its peers in this regard.

That may be because administrative jobs are often seen as more mundane and less romantic than faculty ones. But Berne said he experienced plenty of excitement during his years as vice president.

“Most of my time [at NYU] was as a troubleshooter, and I handled a lot of hot-potato issues,” he said. “Either I gravitated to some of the controversial issues or they gravitated toward me.”

Berne recalled being point person on NYU’s animal testing controversy in the 1990s and the chief negotiator for the first graduate student union contract at a private institution in 2002. The chapter of Tuscan Son devoted to a student sit-in in the president’s office is actually based on a number of student sit-in protests that Berne mediated over the years, including one in 2015 over the treatment of workers on the university’s Abu Dhabi campus and a 2009 student takeover of the cafeteria, during which students issued many of the same demands that the fictional ones make in Berne’s novel.

“University governance is extremely messy,” Berne said. “I thought that university administration and the ambiguity and complexity they have to deal with would be fun to write about in fiction.”

Berne says that his protagonist isn’t necessarily his doppelganger, but Bill’s description of his work as an “academic troubleshooter” lines up closely with Berne’s reflections on university administration.

“If I took on a problem and got it righted, then my bosses could claim most of the credit. If I worked on a problem that I could not fix or, what sometimes happened, things got worse, then my bosses could blame me,” Bill writes. “I never complained about the complexity or difficulty of the problems that came my way; and I was involved in every part of the university.”

Berne had never tried his hand at fiction before. But after decades in what he described as a “pretty high-intensity job,” writing Tuscan Son offered him a kind of gradual off-ramp into retirement. It was also “a lot of fun.”

“I needed a little structure in my life,” he said. “It turned out to be extremely enjoyable.”

Berne said he enjoyed writing Tuscan Son so much that he’s already planning a sequel—and after that, maybe an entire Olmsted literary universe.

“Bill might even get promoted to provost,” he said.

(This story has been updated to correct the name of the fictitious university from Olmstead to Olmsted.)