You have /5 articles left.

Sign up for a free account or log in.

The financial aid formula provides some upper-middle-class families with an implicit subsidy worth thousands of dollars.

zimmytws/Getty Images

Federal student aid awards are technically awarded without regard to race, but researchers detail in a new National Bureau of Economic Research working paper how the financial aid system actually reflects and adds to disparities in wealth among demographic groups.

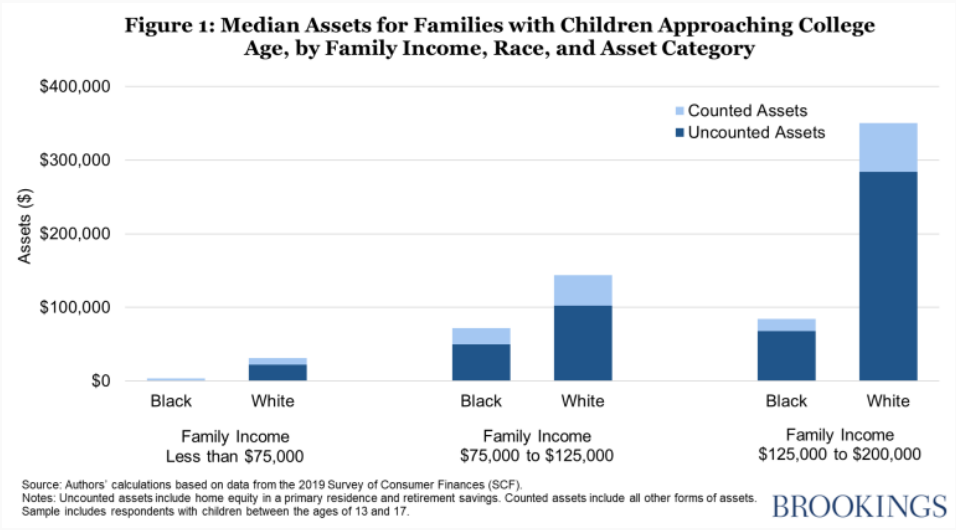

They note that the formula for federal student aid doesn’t consider a family’s retirement savings and home equity in determining how much parents can afford to contribute to their child’s college education—a figure known as the Expected Family Contribution—advantaging upper-income white families, who tend to have larger retirement savings and home equity, over upper- and middle-income families of color.

“Racial disparities creep into the system because the federal formula for estimating how much a family can afford to pay for college ignores a family’s home equity in their primary residence and the value of their retirement savings. Families that own more of these ‘uncounted’ assets have greater financial resources than families that do not,” the authors of the paper, wrote in article about their research. “Yet at similar income levels and other asset holdings, families that own their home or have retirement savings are given the same level of financial support for college as those without.”

They said their research shows that “white families are far more likely to own these uncounted assets and at higher levels, which generates racial disparities in college affordability.”

The researchers, Phil Levine, a professor of economics at Wellesley College in Massachusetts, and Dubravka Ritter, a research fellow at the Consumer Finance Institute at the Federal Reserve Bank of Philadelphia, calculated that not counting certain assets in the formula essentially amounts to an “implicit subsidy” worth thousands of dollars, with white students receiving a higher subsidy.

Their paper has not yet been peer-reviewed.

Families with assets that aren’t counted in the formula generally are able to use their own funds to cover a portion of college costs, while other families with the same expected family contribution are turning to loans to pay those costs, Levine and Ritter found.

Families with assets that aren’t counted in the formula generally are able to use their own funds to cover a portion of college costs, while other families with the same expected family contribution are turning to loans to pay those costs, Levine and Ritter found.

Among these families, Black and Hispanic parents rely on loans to pay a larger share of their financial contributions to their children’s college education.

“At private institutions, one-third to one-half of parent contributions among higher EFC Black families comes from debt. For white parents, that figure is more like 10 percent to 20 percent,” the researchers say in their report.

White students receive about $2,200 more in this implicit subsidy than Black students and $800 more than Hispanic students, according to their findings.

“This gap in subsidies is associated with disadvantages in educational advancement and student loan levels,” the report says. “It may explain 10 percent to 15 percent of white students’ advantage in these outcomes relative to Black students and Hispanic students.”

Levine started looking into the issue after talking with the admissions director at Wellesley. Before that conversation, he said it didn’t occur to him that “there were racial dimensions to the awards students got.”

“It’s generating an unnecessary inequity, which has the potential to affect decisions that people make,” he said in an interview.

Nearly a million students are affected by this disparity in financial aid, which is about 10 percent of dependent students enrolled in college and 27 percent of those who are enrolled full-time at a four-year institution and living away from home. Levine noted that low-income students are unaffected by this part of the formula, as are wealthy students who don’t qualify for financial aid. The research compared white, Black and Hispanic families with incomes of less than $75,000, between $75,000 and $125,000, and between $125,000 and $200,000.

“This is a problem that’s pretty specifically targeted at upper-middle-class students,” Levine said.

Levine, author of A Problem of Fit: How the Complexity of College Pricing Hurts Students—and Universities (University of Chicago Press, 2022), hopes his report leads to potential reforms to the financial aid system that could increase racial equity.

Levine and Ritter argue for the inclusion of all the assets in the funding formula and the lowering of the share of income and assets that families are expected to pay for a student’s college education.

“The objective, however, is not to make college more expensive overall, but to redistribute some of those costs to make the system more equitable,” they wrote in the article.

They also don’t want to further complicate the Free Application for Federal Student Aid, which is used to determine financial aid packages. They suggest eliminating instructions on the form that tell students which assets to include in their financial aid applications, or instead asking for a family’s total net worth.

“Either option would make the system more equitable with negligible effects on the complexity of the financial aid process,” they wrote.

Justin Draeger, president of the National Association of Student Financial Aid Administrators, said equity conversations about federal financial aid often come down to conflicts about distribution, which is determined by the formula. The report highlights one of the trade-offs involved in those discussions, and it’s good to understand what those are, he said.

“The report clearly highlights the potential inadequacy in federal methodology, but then we have to balance that against multiple other competing public policies,” Draeger said. “One of those debates is dealing with the fact that the complexity of the formula and application may deter applicants from applying for federal student aid—the very students we most want to get federal student aid, and that’s a debate we’ve been having for decades. I can appreciate where they’re coming from because they are highlighting an inadequacy, but there are competing public policies that we’re also trying to balance this against.”