You have /5 articles left.

Sign up for a free account or log in.

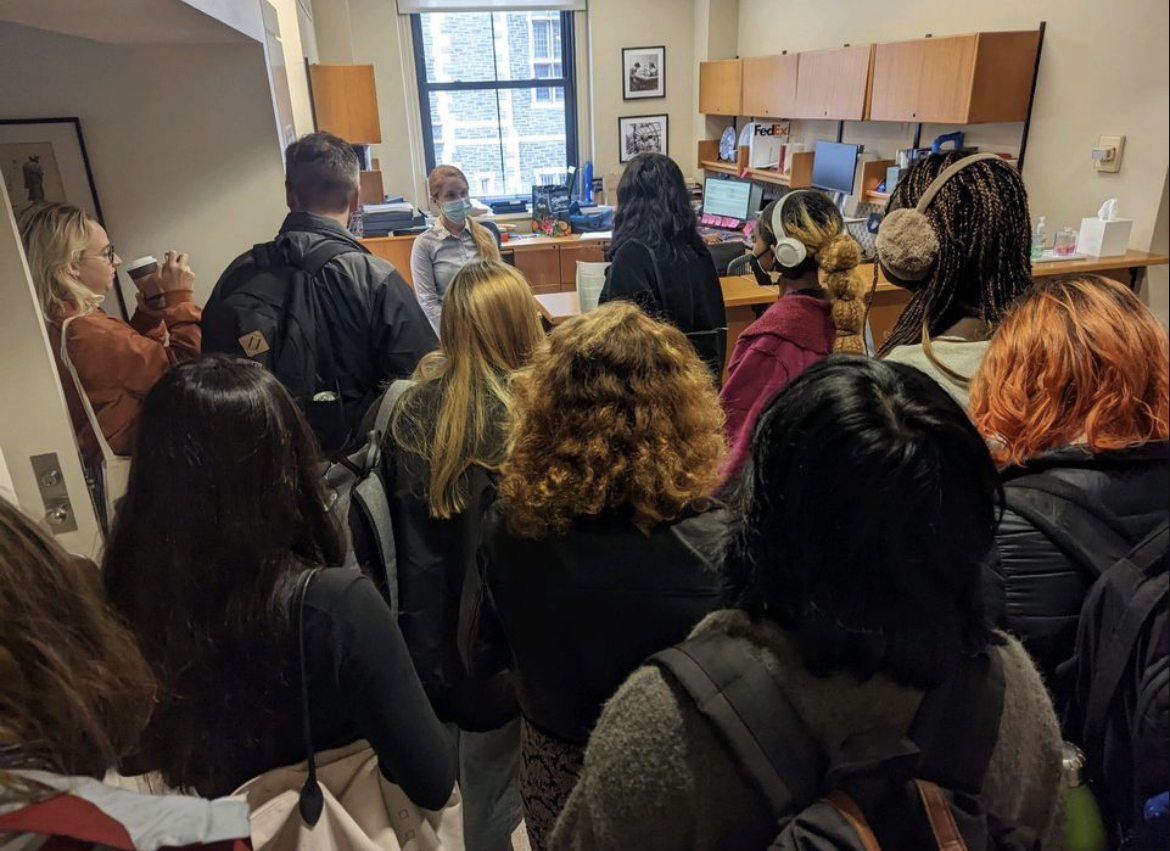

Unionized undergraduate student workers at Grinnell College, including community advisers, attend a bargaining session for their first contract Thursday.

Courtesy of Libby Eggert

A group of resident assistants at Barnard College in New York City walked into the office of college president Sian Beilock on Monday to deliver a letter and a message: 95 percent of them had voted to unionize. They asked for the college’s “support”—or voluntary recognition—within five business days.

“Our responsibilities and lack of pay impact our ability to both effectively serve our residents as well as take care of ourselves as students,” the letter read. “We have collectively decided that forming a union will empower us to better pursue our shared mission not only for current RAs, but all generations that follow.”

The college responded with a statement: “Barnard deeply values our Resident Assistants and the College is committed to ensuring they have the best possible experience in their roles as student leaders on campus,” it read. “We are reviewing this petition.”

Katie Cherven, a junior and an RA, said she’s optimistic that the college will voluntarily recognize the union.

“Barnard very much positions itself as a social justice–oriented institution, and I’m very hopeful they will center that in their decision,” she said.

But she added that RAs aren’t asking for permission; if the college doesn’t give the union its blessing, they are prepared to strike.

Undergraduate unions are exceedingly rare, and unions representing residential assistants at private colleges are even rarer. But the events at Barnard are part of a slowly growing trend.

Days before Barnard students delivered their petition, student Resident Life employees at Mount Holyoke College filed for union recognition with the National Labor Relations Board after the college failed to respond to their request for voluntary recognition.

Keely Sexton, Mount Holyoke's media relations manager, told Inside Higher Ed by email that the college “appreciates the hard work and dedication that our student employees bring to the jobs they perform while pursuing their academic careers” and “supports the right of workers to choose what they believe is best for them.”

In March, Wesleyan University voluntarily recognized a union of undergraduate residential life employees, making it the second such bargaining unit in the country. A few months later at Grinnell College in Iowa, community advisers (Grinnell’s term for RAs) were brought into the fold of the expanded undergraduate worker union, which initially only included student dining workers.

RAs at peer institutions are trying to seize the momentum from these victories, hoping to capitalize on the pressure for their progressive liberal arts schools to live the values they claim to espouse. Cherven credits the growing popularity of unions among young people with propelling the recent undergraduate bargaining campaigns.

“It’s a very exciting time for the unionization movement,” Cherven said. “I think there’s been a really exciting resurgence among young employees, and that’s really motivating.”

She added that it took some time for the Barnard union campaign to win widespread support among RAs, but eventually they bought in.

“There was and is some hesitation, because we work where we live and the threat of losing our jobs would therefore mean losing our housing,” she said. “But the more of us there are, the more powerful we are. We have to remember that and recognize that it’s worth taking that risk if we’re all taking it together.”

‘Essentially a Full-Time Job’

Resident assistants—also known as resident advisers, community advisers, hall leaders and myriad other titles—play a crucial role in the administration of residential life at colleges and universities. They organize social events for underclassmen, report dangerous or illicit behavior, and even act as first responders during medical and mental health emergencies. Compensation for these roles varies, from free or reduced room and board to stipends and hourly wages.

Every RA or CA that spoke to Inside Higher Ed said that, as student workers, they shoulder too heavy a burden and work far more hours than the job should entail. Moreover, they said they aren’t given the respect or compensation they deserve.

“We’re expected to be able to handle anything thrown at us,” said Cherven, who works another 20 hours a week outside of her RA position. “It is essentially a full-time job.”

“A big part of our job is being available to our residents 24-7,” said Libby Eggert, a sophomore community adviser at Grinnell, where students receive a housing grant but no stipend or meal plan. “We deserve compensation for that.”

Hannah Yi, a Barnard junior and resident assistant, said the road to union organizing on her campus began this past May, when RAs who signed up to work the summer semester found they would be on campus without a meal plan for over a month. Yi, who was scheduled to work 18 weekend shifts, was assigned to a hall without a refrigerator; to save money, she ate granola with water almost every day.

Hannah Yi, a Barnard junior and resident assistant, said the road to union organizing on her campus began this past May, when RAs who signed up to work the summer semester found they would be on campus without a meal plan for over a month. Yi, who was scheduled to work 18 weekend shifts, was assigned to a hall without a refrigerator; to save money, she ate granola with water almost every day.

Yi said that when she and the other summer RAs went to the office of residential life to ask for a meal plan and reduced hours, they were met with condescension and resistance—so they threatened to strike. Soon after, they were issued $550 food delivery app gift cards for the remaining weeks before their meal plans kicked in.

After that, Yi said the RA organizing committee grew, and the goal changed from winning short-term battles to unionization. By the time the RAs delivered their petition to President Beilock, the aspiring union had won the support of 95 percent of the group.

“That really galvanized the movement as it is now, because the amount we were able to achieve through collective action and by threatening to strike was so great,” Yi said. “It showed us that the only thing that’s going to make this kind of change sustainable is a union.”

Solidarity Takes Forever

Until the victory at Wesleyan, only one institution’s undergraduate resident assistants were unionized: those at the University of Massachusetts at Amherst, where student workers organized the first such bargaining unit in 2002. Twenty years later, more are finally, slowly starting to win support and recognition.

Public university employees are governed by state laws, and private colleges are subject to the policy decisions of the National Labor Relations Board. Students at Barnard and Mount Holyoke are acting on a precedent set by that board in 2017. After ruling that graduate student workers at Columbia University qualified as union-eligible employees, the NLRB also ruled that resident assistants at George Washington University could unionize, paving the way for other undergraduate workers at private institutions to do so.

But the union election at GW was ultimately canceled, and despite the groundbreaking precedent, no undergraduate RA union campaign succeeded for the next five years.

William Herbert, executive director of the National Center for the Study of Collective Bargaining in Higher Education and the Professions at Hunter College, said frequent turnover—read, graduation—and the NLRB’s waffling on its student worker policy have hampered RAs’ ability to run successful unionization campaigns.

At Georgetown University, a four-year unionization campaign ended unsuccessfully when its leaders graduated in 2020. In 2018, a union petition submitted by student housing advisers at Reed College in Portland, Ore., was withdrawn after the NLRB under President Trump proposed reversing its Obama-era ruling that made student workers eligible for union representation.

And, in a case that could have broad implications for undergraduate labor, community assistants and other student workers at Kenyon College in Ohio have been locked in a heated battle with their institution since Kenyon refused to voluntarily recognize their union in 2020. In 2021, the administration successfully filed for a motion to postpone NLRB-mediated union elections.

In its motion, Kenyon argued that following the election rules of the National Labor Relations Act would force the college to violate its students’ rights under the Family Educational Rights and Privacy Act by requiring the college to submit to the NLRB a list of unit members’ “full names, work locations, shifts, and job classifications.”

Kenyon spokesperson David Hoyt wrote in an email to Inside Higher Ed that before any election can be held, the NLRB “has to work through, among other considerations, the challenges that FERPA presents in the context of its proceedings.”

But Kat Ellis, a community adviser at Kenyon, said she suspects that this argument and other actions taken by the university are disingenuous, designed primarily to give the college a leg up in its fight to stop a union vote. She said CAs at Kenyon were paid an hourly wage until this semester, when they switched to a stipend—a move that Ellis says could help Kenyon make the case that its CAs are more like students than employees.

“It’s very odd,” she said. “I think their recent change to pay us with stipends gives them a stronger argument to the NLRB.”

Herbert said that while the compatibility of the NLRA and student-college legal relations is under review, RAs' ability to bargain collectively is, for now, largely in the hands of colleges and universities.

“Each institution will examine each case and decide what’s in their interest, based on what their values are towards labor issues and the idea of representational democracy, which is what collective bargaining is,” he said.

Student Worker: Oxymoron or Reality?

The NLRB’s 2017 decision to allow undergraduates at private colleges to unionize had detractors in higher education: a group of organizations, including the American Council on Education and the Association of College and University Housing Officers–International, filed an amicus brief in support of GW and later condemned the NLRB’s ruling against it.

Steven Bloom, the assistant vice president for government relations at ACE, said his organization’s position on undergraduate worker unions hasn’t changed: he still believes that classifying students as employees with collective bargaining rights was a mistake—one he hopes is overturned.

“It’s not because we don’t support the notion of collective bargaining. We just think that, at their heart, these are students, not employees,” Bloom said. “Being an RA is part of the academic experience … [unionizing] is a troubling intrusion into the relationship of the student to that institution, and brings into that relationship a third party that complicates it in ways that aren’t helpful to achieving the academic mission.”

Every student worker interviewed for this article said that while they enjoyed organizing community events and helping their peers, being an RA was, for them, a job—one that they felt was rewarding, but whose main purpose was to help them and their families make ends meet.

“This is our livelihood,” said Eggert, the Grinnell CA. “We deserve to have a say in it.”