You have /5 articles left.

Sign up for a free account or log in.

Everest College in Santa Ana, Calif., owned by Corinthian Colleges, shut down along with Corinthian’s other campuses in 2015. The high-profile closures led to increased interest in the causes and effects of college closures.

MediaNews Group/Orange County Register via Getty Images

A new report finds that the closure of a college or university has a devastating effect on the educational attainment of the students enrolled at the time.

The study, produced by the National Student Clearinghouse and the State Higher Education Executive Officers Association, followed 143,215 students who were enrolled in 467 institutions that closed between July 1, 2004, and June 30, 2020. Those that closed generally enrolled larger populations of students of color than institutions that remained open—55 percent versus 46.4 percent—and more Pell Grant recipients as well.

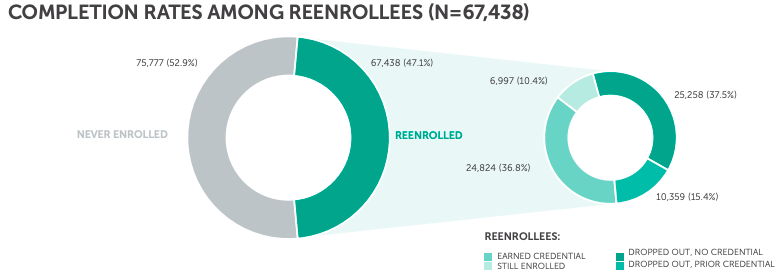

Just under half the students whose institutions closed—47.1 percent—re-enrolled at another college or university. Of those who re-enrolled, only 36.8 percent went on to earn a credential; 52.9 percent dropped out, and 10.4 percent were still enrolled as of February 2022. Students of color, male students and non-traditional-aged students were the least likely to re-enroll and complete a credential.

It’s not surprising that institutional closures can have negative effects on students; such closures often leave students scrambling to find another program that will suit their needs and accept their existing credits. But thanks to longitudinal data collected by the NSC, this is the first study to so thoroughly track the outcomes of students whose institutions are shuttered, according to the researchers involved.

The first of three reports on college closures from NSC and SHEEO, the study recommends that regulators take steps to lessen the blow for affected students. Among other things, they should better monitor institutions’ financial health so that abrupt closures are less likely and require institutions to provide support for students if closure is imminent.

Those supports include teach-out agreements, which are contracts that state another institution is willing to take on the students of the closing institution. They are more concrete than teach-out plans, which merely provide guidance on where a student can study after a closure.

“Once it becomes likely an institution will close, states need to ensure teach-out agreements are in place to provide all students with a pathway for completing their credentials,” the study reads. “Additionally, states need to thoroughly vet the teach-out institutions to ensure they are capable of completing the terms of the teach-out agreement and are financially viable.”

Many students took time off before entering a new institution, with 26 percent re-enrolling more than a year after their previous college or university closed, the study found. These students were far less likely to receive a credential than those who re-enrolled earlier, it noted, reinforcing the importance of giving students an immediate option to transfer to another institution.

Interest in college and university closures has grown in the past 10 or so years, said Clare McCann, a higher education fellow at Arnold Ventures, a philanthropic organization, who reviewed the study ahead of publication. McCann, who has researched college closures in the past, said that high-profile closures, including that of Corinthian Colleges, a large for-profit network of campuses that shuttered in 2015, led policy makers to take a closer look at the causes and effects of such shutdowns.

“People have been trying to make sure that doesn’t happen again,” she said. “What’s important is that the policies are put in place for all schools that are at a serious risk of closure so that we’re making sure institutions … are getting all their ducks in a row before anything happens.”

Indeed, students were more likely to suffer negative outcomes if they experienced an “abrupt” closure rather than an “orderly” one. Among the 70 percent of students whose institution closed abruptly, only 40 percent re-enrolled, compared to 63.7 percent of students who experienced an orderly closure.

To differentiate an abrupt closure from an orderly one, researchers looked at a number of factors, including the amount of time between the announcement and the closure itself (less than a month is considered abrupt), whether the institution had prepared a teach-out plan, whether any news articles described the closure as abrupt, and other factors.

David Chard, the former president of Wheelock College, a private Massachusetts institution that closed in 2018, doesn’t find it surprising that abrupt closures are so detrimental to student progress; he noted that some students struggled with the closure of Wheelock, which became part of Boston University, despite having ample warning and support from both the college and BU.

“We had a largely successful student body, even first-generation, students of color, students from low-income backgrounds,” said Chard, now the dean of Boston University’s Wheelock College of Education and Human Development. “[But] for many of them it was still really challenging, because they’re working with a whole new group of administrators they have to build relationships with, whole new sets of systems they have to understand.”

Colleges that know in advance they’re likely going to close are being “negligent” if they wait to tell students, he said.

The report also delves into what types of colleges and universities closed. For-profit institutions made up the majority of closures: just about half of the institutions in the study were private, for-profit two-year institutions, and 28.1 percent were private, for-profit four-year institutions. For-profit universities were also more likely than their nonprofit counterparts to close abruptly.

Just under 18 percent of the institutions that closed were private four-year nonprofits, 3.4 percent were private two-year nonprofits and the remaining 0.9 percent were public four-year institutions. The researchers noted in a press briefing that nonprofit closures are becoming more common.