You have /5 articles left.

Sign up for a free account or log in.

Charlie Baker, governor of Massachusetts, is the new president of the NCAA.

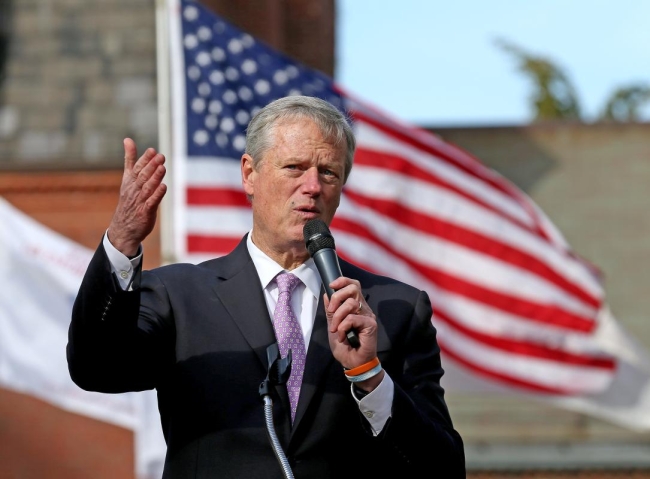

MediaNews Group/Boston Herald via Getty Images

Charlie Baker, the departing Republican governor of Massachusetts, will be the next president of the National Collegiate Athletic Association, the organization announced Thursday.

He will be the first NCAA president with no professional collegiate experience—either in athletics or institutional leadership—in the organization’s 113-year history, a sign that its future is more enmeshed in politics than ever. His appointment also ends 20 years in which college presidents led the primary association of intercollegiate sports.

Baker, whose two terms as governor will end in January, acknowledged his anomalous background in a news conference Thursday afternoon.

“When I was first approached about this, my initial reaction was that I was not exactly a traditional candidate,” he said. “But there is an enormous amount of transition associated with policy, government, rules and regulations that will be a big part of the next act when it comes to the NCAA.”

“The challenges that we face are big, complex and urgent, as we think about the future of college athletics and the legal, political and cultural environments that have changed drastically,” Linda Livingstone, president of Baylor University and the chair of the NCAA’s Board of Governors, said during the news conference. “When you consider the priorities that we have right now in the NCAA, it’s hard to imagine a better fit.”

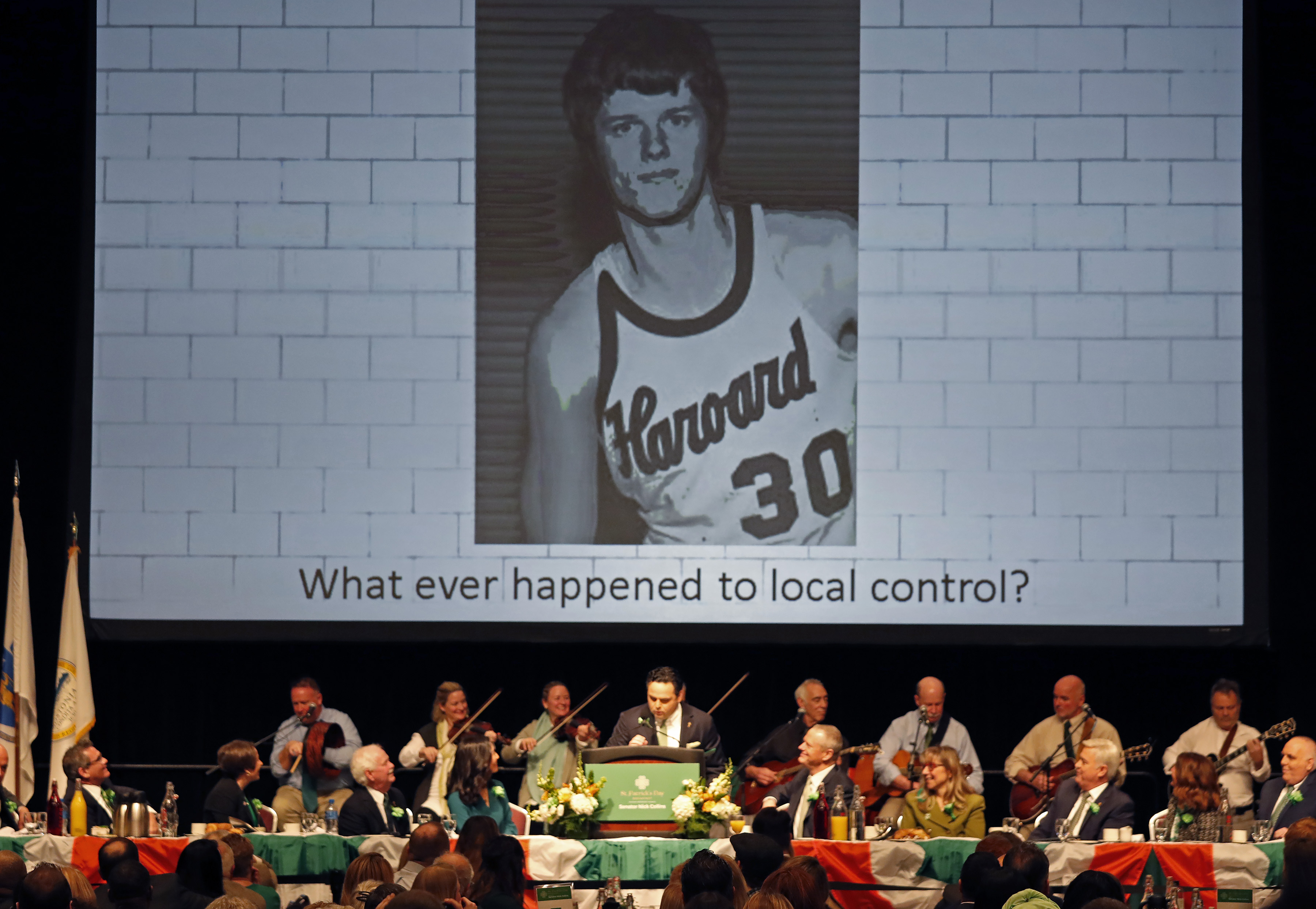

While Baker has no professional experience in college athletics, he did play for Harvard University’s basketball team as an undergraduate and even served as an assistant coach for the JV team during his senior year. He wife was a college gymnast, and two of his sons played college football.

A ‘Consensus Builder’ for Indianapolis and Washington

Baker will take the helm at the NCAA in March, at a time of uncertainty and potential transformation for the embattled organization and the amateur model of college athletics, which its leaders have defended for years in courts of law and public opinion.

Last year, the U.S. Supreme Court ruled that the organization could not bar athletes from receiving education-related compensation in Alston v. NCAA. A similar case, Johnson v. NCAA, could soon upend college athletics even further by asking the court to determine whether athletes should be considered employees of their institutions. And pending legislation, including the College Athlete Bill of Rights that was reintroduced in the U.S. Senate in August, also threatens to reshape college athletics and the NCAA.

Last year, the U.S. Supreme Court ruled that the organization could not bar athletes from receiving education-related compensation in Alston v. NCAA. A similar case, Johnson v. NCAA, could soon upend college athletics even further by asking the court to determine whether athletes should be considered employees of their institutions. And pending legislation, including the College Athlete Bill of Rights that was reintroduced in the U.S. Senate in August, also threatens to reshape college athletics and the NCAA.

As if to drive home the challenges that face Baker, just hours after his appointment was announced, the director of a regional office of the National Labor Relations Board found that the NCAA, the Pacific-12 Conference and the University of Southern California legally “employ” college football and basketball players, and that the NCAA had engaged in unfair labor practices against them.

Walter Harrison, a former president of the University of Hartford and a longtime member of the NCAA’s inner circle of college presidents, told Inside Higher Ed he was surprised by the choice but that Baker “may turn out to be exactly who the organization needs right now.”

That need, Harrison said, relates to the NCAA’s desire to broker an agreement with Congress to grant the organization an exemption from federal antitrust rules, which the Supreme Court ruled it had violated in the Alston case. This exemption, Harrison said, would allow the organization to cap coaches’ salaries and regulate how institutions can use promises of profits from athletes’ name, image and likeness deals to woo students—effectively an off-the-books form of compensation.

“He’ll be able to navigate Washington in a way the NCAA has proven to be ineffective in the past five years,” Harrison said.

However, Harrison added, the politics of higher education—and especially of college athletics—are different from, and in some ways more complicated than, the world of state and national politics that Baker is more familiar with.

“He’s done well in the politically charged climate of Boston, but it’s going to be a whole new level of political intensity at the NCAA … There’s absolutely no central point of agreement among any of the member conferences and schools,” Harrison said. “I’m reminded of a quote attributed to Woodrow Wilson: ‘I learned the fine art of politics on the faculty at Princeton and then went to Washington to practice among the amateurs.’”

‘Pulling a Rabbit Out of a Hat’

Baker will start in March and succeed Mark Emmert, a former president of the University of Washington who led the organization for 12 years before his retirement was announced in April—a “mutual decision,” despite his contract having been extended to 2025 last year.

Andrew Zimbalist, an economics professor at Smith University and the author of Unwinding Madness: What Went Wrong With College Sports and How to Fix It (Brookings Institution Press, 2017), said that Baker not only has the challenging—and perhaps thankless—job of stewarding a fractious and precarious organization; he also has to “clean up the mess” left behind by Emmert, who Zimbalist said “never did anything right.”

“The NCAA was already somewhat dysfunctional, but it has become completely dysfunctional,” he said. “The only way they can even begin to think about salvaging the system is by getting Congress to pass antitrust exemption legislation.”

Zimbalist said he thinks Emmert’s shortcomings give Baker an easy out, even if he’s not able to accomplish much.

“I suspect [Baker] looks at the situation and says, ‘Well, it’s so grave at this point that if I can’t rescue it, nobody’s going to blame me,’” Zimbalist said. “‘And if I do succeed, not only have I elevated my brand and popularity, but I’m going to be able to project myself into national politics.’”

During the press conference, Baker was asked “why anyone would want to take this job” in light of the chaotic state of college athletics.

“As someone who really believes in the power of collegiate sports to do all sorts of amazing things—for communities, for schools, for alumni and for student athletes—I think it’s worth doing,” Baker said. “Yeah, it’s big and complicated. So are a lot of things I’ve done in my life.”

Zimbalist said Baker’s history of calm, bipartisan management is promising, but he’s not sure anyone could accomplish what the NCAA needs to in order to preserve its current form.

“Baker is a good manager, at least in my view … but it’s going to be especially difficult to work with Congress right now,” Zimbalist added. “They’re basically looking for him to pull a rabbit out of a hat.”

Harrison said he’s not sure, either, but he’s hopeful—and the stakes, he said, are higher than ever.

“There’s so much money flowing into intercollegiate athletics, especially big-time football, that without [congressional action], I think it’s going to become uncontrollable,” he said. “It could mark the beginning of the end of intercollegiate athletics as an important part of American higher education.”