You have /5 articles left.

Sign up for a free account or log in.

Nearly 100 pages of consumer complaints were included in a trove of documents analyzed by the Student Borrower Protection Center for a new report.

Courtesy of the Student Borrower Protection Center

The Education Department failed to control its debt collection system during the COVID-19 pandemic, which led to thousands of people having their wages illegally garnished, a new report finds.

The department’s failure to stop wage garnishment once student loan payments paused, as directed by Congress, has been the subject of lawsuits and an inspector general report. But the Student Borrower Protection Center found in the report released Thursday that the problem persisted longer than previously known, through at least August 2021—18 months after Congress passed a set of student loan relief policies as part of the CARES Act.

“The situation that defaulted borrowers faced during COVID-19 is emblematic of the central, existential flaw in the administration of wage garnishment: once started, ED cannot guarantee that wage garnishment will stop, even when required by law,” the report stated.

Experts with the Student Borrower Protection Center and lawmakers called on the department to end the practice of going after wages of borrowers in default until it can ensure that the system can be deployed lawfully. The department is allowed to garnish wages but not required to.

“This report shines light on a troubling issue that’s been going on for far too long,” New Jersey Democratic senator Cory Booker said in a statement. “Urgent steps are needed to reform the harmful wage garnishment process in order to protect the most financially vulnerable student loan borrowers.”

The Education Department did not respond to a request for comment on the report by this article’s deadline.

The June 2021 inspector general report found that the Office of Federal Student Aid took quick action and “generally achieved positive results” in suspending most wage garnishments and refunding payments back to borrowers.

“The Department of Education will continue to evaluate its authorities with respect to administrative wage garnishment to understand what improvements may be made, including improvements that would avoid employer noncompliance with pauses in garnishment,” the agency wrote in response to the inspector general’s report.

The Student Borrower Protection Center findings highlight some of the challenges the Biden administration will have to contend with when student loan payments eventually resume. Currently, 8.2 million borrowers have defaulted on a federal student loan, according to the report. Payments have been turned off since March 2020 and could resume next year after lawsuits challenging the Biden administration’s debt relief plan are resolved.

“This investigation is a troubling reminder of what we already knew: the predatory debt collection system is out of control,” Massachusetts Democratic representative Ayanna Pressley said in a statement. “It’s clear that under two administrations—one with contempt for the people and one with compassion—the agency was unable to rein in these unconscionable and explicitly banned wage garnishments.”

The Student Borrower Protection Center analyzed a trove of documents obtained by the National Student Legal Defense Network via a Freedom of Information Act request, which showed systemic problems with the department’s administrative wage garnishment system. For example, the department’s databases for borrowers and employers who garnish wages “were riddled with glaring gaps,” and Maximus, the department’s loan servicer for accounts in default, resorted to googling employers to find their contact information, the center found. In some cases, Maximus employees seemed ready to give up in trying to reach all the employers who continued garnishing employees’ wages.

“Our findings demolish any illusion that the Department of Education might have its arms around its ravenous debt-collection machinery,” said Persis Yu, deputy executive director and managing counsel at the Student Borrower Protection Center. “If ED can’t guarantee that its debt collection tool can comply with consumer protections, it should never turn this machinery on again.”

The documents covered the period from March 2020 to summer 2021.

“By the end of the period covered in the FOIA Release, dozens of borrowers were still facing garnishments each week, and ED was still scrambling to end these collections,” the report states.

The center said in the report that it’s not clear whether the situation has changed.

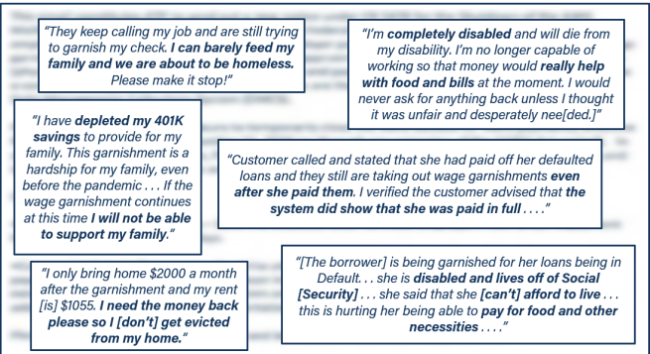

The documents included nearly 100 pages of complaints from borrowers who sought help from the Education Department after their wages were garnished despite the payment pause. Some borrowers faced garnishment for loans already paid off, while others feared eviction and used their retirement funds to cover other living costs.

“My work hours have been drastically cut, although I am grateful that at least [I] still have my job, however I need more relief and was told that would be provided,” wrote one borrower who had 15 percent of their wages taken. “I haven’t been able to pay my rent and insurance and other bills trying to stock my home on essential things to survive this pandemic and I’m still having $400 taken from me every two weeks. How can my family and I survive?”

Borrowers reported challenges in getting ahold of their loan servicer, and those who did were sometimes given wrong information, according to the report.

“Reports like this one and the others included here should be a wake-up call for those who would frame the student loan system’s failures during the pandemic as a set of unfortunate but excusable operational hiccups—let alone as ones that can be rectified with a check in the mail,” the report states.