You have /5 articles left.

Sign up for a free account or log in.

Black college students have lower completion rates than any other demographic; a new survey tries to gauge the reasons why.

Getty Images

College completion rates of Black students are lower than those of any other ethnic or racial group: 34 percent of Black Americans have an associate degree or higher, compared with 46 percent of the general population, according to a recent report from the Lumina Foundation.

The reasons for this attainment gap are varied, but Black students say the biggest obstacles they face are cost, a lack of extracurricular support and “implicit and overt forms of racial discrimination,” according to a new joint study by Lumina and Gallup.

“We’ve seen Black student enrollment and completion declining over the last 10 years, and it continues to decline post-pandemic,” said Courtney Brown, Lumina’s vice president of strategic impact and planning. “This study is important because it begins to tell us why—not from experts on the outside but from students themselves.”

The study is based on a survey that asked more than 6,000 currently enrolled students—including 1,106 Black students—about the challenges they face in higher ed that make degree completion difficult. The survey found that Black students are far more likely to experience racial discrimination than their non-Black peers, and those enrolled at less diverse institutions reported experiencing discrimination more often.

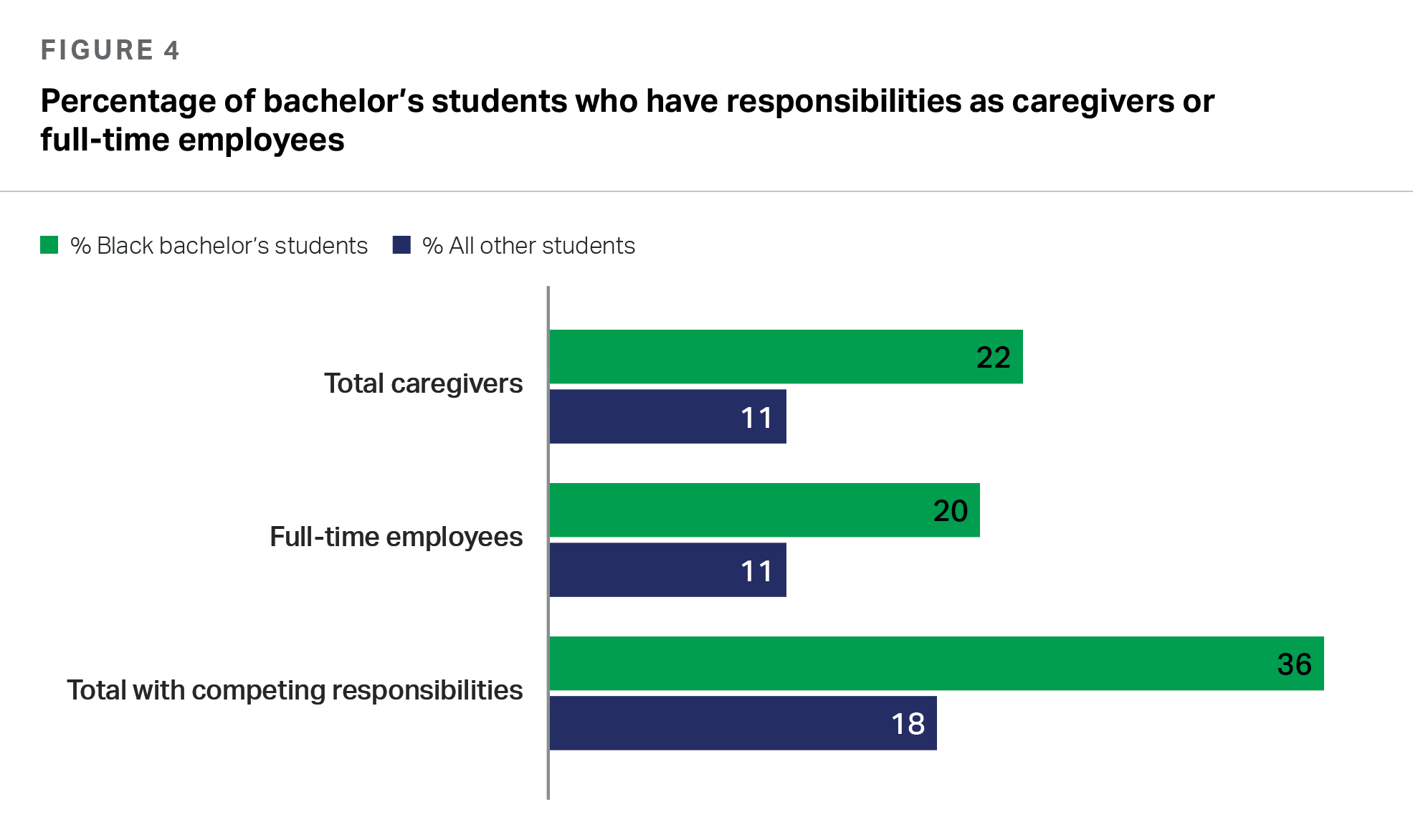

It also found that Black students are more likely than any other group to have a full-time job or significant family caregiving and wage-earning responsibilities—factors that they indicated make it difficult to succeed in college.

Shaun Harper, executive director of the Race and Equity Center at the University of Southern California, said the results were disheartening but not surprising.

“The data are painstakingly clear: Black students are underserved in higher ed,” he said. “Very few institutions have a Black student success strategy … Until and unless there’s actual institutional strategies with key performance indicators and accountability metrics, we’re going to continue to see, in report after report, these gaps in Black student success and attainment.”

Discrimination Tied to Dropouts

Brown said one major takeaway from the survey is the importance of cultural inclusion and antidiscrimination efforts in closing the achievement gap for Black students across all types of institutions and programs.

“There are a number of material things that can be done to make college success more achievable for Black students—financial aid, tuition reductions, support for childcare—but that’s not the only answer,” she said. “It’s cultural, too. The survey really shows that discrimination is a big issue.”

According to the report, 21 percent of Black students said they felt discriminated against “frequently” or “occasionally” in their program, compared to 15 percent of all other students. Those enrolled at institutions with the least racially diverse student bodies were nearly twice as likely to say they felt discriminated against as those at diverse institutions; they were also more likely to say they felt physically or emotionally unsafe on campus.

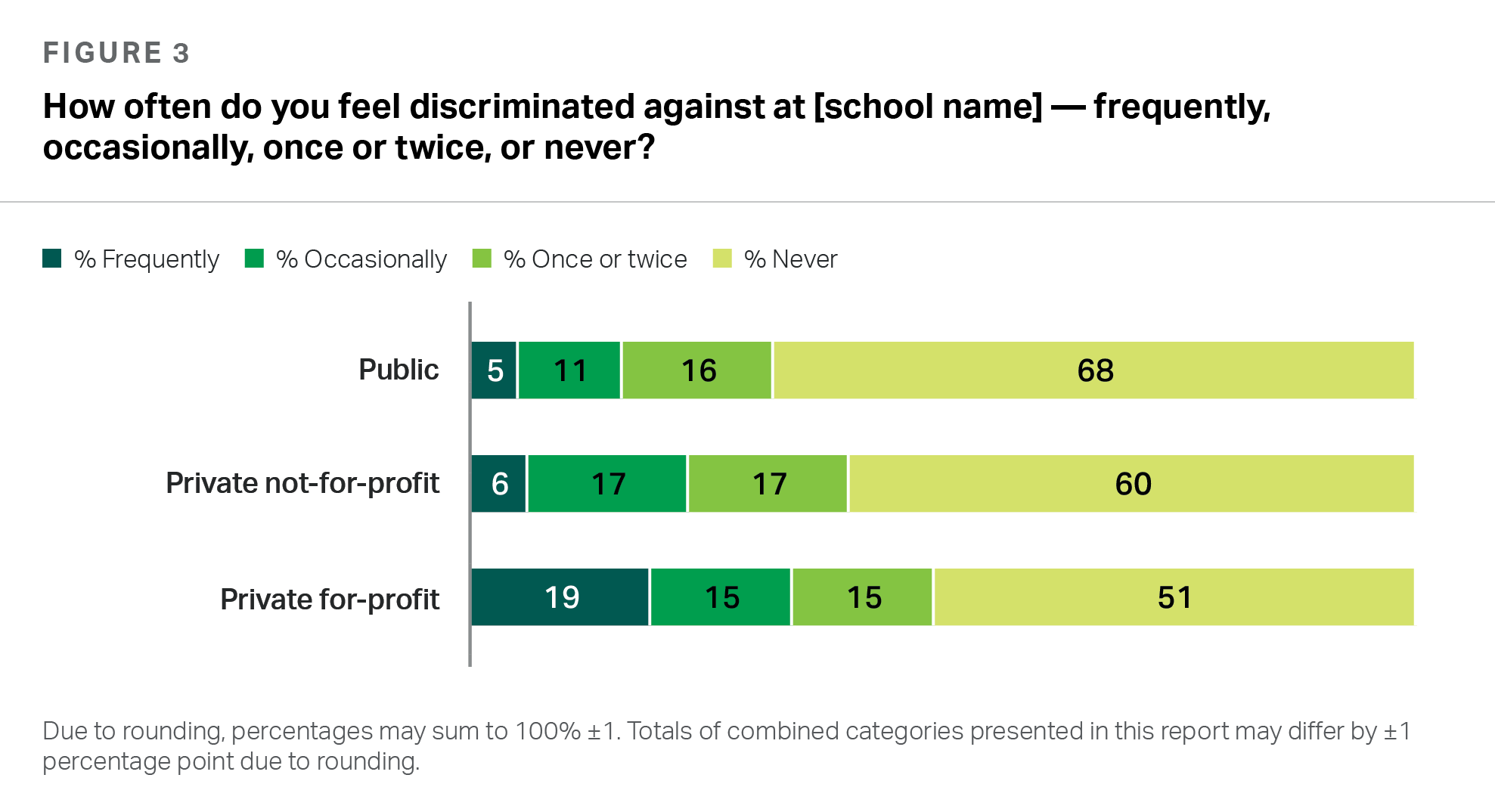

The study found significant disparities by program and institution in the level of discrimination Black students faced. Those at private nonprofit colleges and universities said they were more likely to experience discrimination (23 percent) than those at public institutions (17 percent). In addition, students enrolled in short-term credential programs and for-profit institutions reported more discrimination than those enrolled in bachelor’s or associate degree programs at private nonprofit or public institutions.

Brown attributes the disparity to a variety of factors. For one thing, Black students are more likely to attend for-profit colleges than any other group; as of 2018, they made up 21 percent of for-profit students but just 13 percent of the students at nonprofit and public four-year institutions, according to the National Center for Education Statistics. Black students are more likely to be exploited by and indebted to for-profit colleges than other groups—a potential symptom of discrimination or lack of support for students with unique material and cultural needs.

Meanwhile, short-term credential programs are populated largely with—and taught mainly by—white men, Brown said.

Black students “are walking into an environment that is predominantly white, older, male, that is likely not welcoming, that likely has outdated curriculum with instructors that don’t look like them or can’t mentor them,” she said. “They don’t feel like they belong.”

Harper said that while the conversation around discrimination on campus and the rise of antiracist policies has exploded since the murders of George Floyd and Breonna Taylor in 2020, not enough institutions have taken action.

“Recently, more people in higher ed are talking about antiracism … but to continue to do nothing to better serve Black students is also a kind of racism,” he said.

To Earn or to Learn?

For many demographic groups, enrollment and attainment declines have been tied in part to growing doubts about the value of higher education and a sense that alternative pathways to economic stability are less expensive and just as effective. But Brown said that while the opportunity cost of going to college is a major factor in the attrition rates of Black student, skepticism about higher ed’s value is not.

“Those that value [higher ed] the highest are people of color: Black students, Latino students, way higher than white students. So that’s not the issue here,” she said. “It’s the in-the-moment needs, thinking, ‘I have to take care of my family and so I have to make money.’ It’s a question of priorities.”

The survey found that 35 percent of Black students in the U.S. have major life responsibilities beyond coursework, and 22 percent are caregivers for children or adult family members, double the average for other student groups. In addition, 20 percent of Black students in four-year programs were balancing coursework with a full-time job—twice as many as all other bachelor’s candidates.

Addressing the completion gap, then, Brown said, doesn’t call for making a stronger pitch to Black students about the benefits of higher ed; rather, it requires committing to material support that can help make two or four years in college feasible for those who are low-income.

“The pandemic created all kinds of issues, and one is that people could get a job making more money than they would pre-pandemic,” Brown said. “These are low-wage jobs that aren’t going to last or create generational wealth … but if you can make $15 or $20 an hour, it’s hard to stop doing that to enroll in a degree program when you’re responsible for taking care of your family.”

Some helpful first steps would be to increase childcare options and need-based scholarships, open food pantries, and offer flexible class delivery methods, Black students said in the survey. Flexible classes were deemed especially important; 47 percent of Black respondents said having the option to go remote or hybrid was “very important,” compared to 29 percent of other students.

“Institutions need to meet their students where they’re at, and that has to include Black students,” Brown said.

Harper has been working for years on an unpublished research project to calculate revenue losses from Black student attrition rates at public colleges and universities. He said that even before the pandemic and the impending “demographic cliff,” the failure to retain Black students has cost institutions dearly.

“In addition to failing these students, institutions fail themselves financially when they don’t create the conditions that lead to more Black students persisting and completing, because when [students] leave, they take their tuition payments, Pell Grants and student loans with them,” said Harper, who is also a professor of business and education at USC. “The consequence, for many institutions, is millions of dollars every year.”

That cost may multiply in the years to come, Brown said, as the long-anticipated demographic cliff approaches and college-age Black students—whose population is increasing, along with other groups of students of color—become a crucial demographic for institutions facing enrollment declines.

Brown said she hopes the survey offers some clarity and context to the retention gap for Black college students and drives a response beyond words.

“This data really gives us a glimpse into some things that can be done, rather than guessing,” Brown said. “Institutional leaders and policy makers need to look at these results and say, ‘We have to do better, and here are areas we can address immediately.’”

Jhenai Chandler, director of college completion at the Institute for College Access and Success, a nonprofit research and advocacy organization focused on affordability, accountability and equity in higher ed, said the report shows the reality of the Black student experience and its challenges—a reality that she said is often ignored by institutions and policy makers.

“We feel as a country that segregation was so long ago, but it wasn’t; the effects of that are still really being felt by these current generations,” she said. “Institutions need to make sure they’re addressing those issues that can really stop high-performing, capable students from completing their education.”