You have /5 articles left.

Sign up for a free account or log in.

Inflation is one of many financial pressures that experts expect to result in higher college tuition.

Anadolu Agency via iStock/Getty Images Plus

Stanford University will raise undergraduate tuition by 7 percent for the upcoming academic year, citing inflation, which has squeezed institutions and consumers alike across the U.S.

The move marks a significant jump from the 4 percent tuition increase Stanford’s Board of Trustees approved last year. Experts say Stanford is an outlier in the size of its tuition increase, though they expect numerous other institutions to raise sticker prices in the coming months.

Attending Stanford now costs upward of $82,000 a year, including room, board and the listed tuition price.

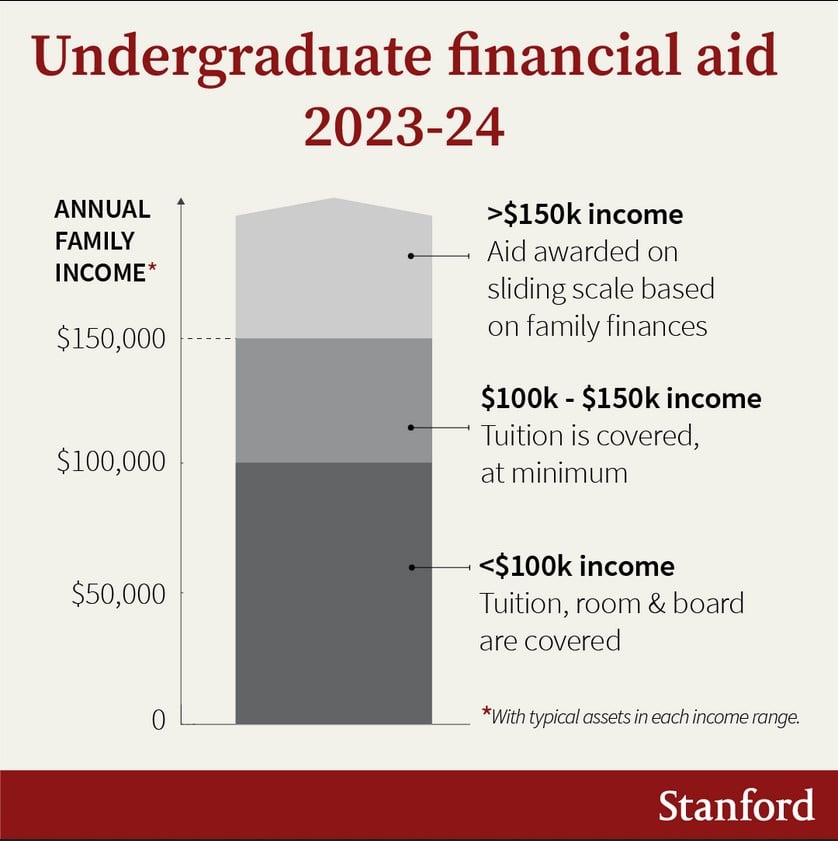

The silver lining for many students is that the university is also expanding financial aid, raising the income threshold for free tuition, room and board from $75,000 to $100,000. According to Stanford’s website, students with annual family incomes between $100,000 and $150,000 will at a minimum have tuition covered by the university.

Experts note that students at other universities without such deep pockets will likely feel the pain of inflation pricing as tuitions start to rise.

The Stanford Breakdown

A university spokesperson noted by email that “Stanford has for many years committed to providing sufficient scholarship support so that parents with annual incomes below a certain threshold, and assets typical of that income level, are not expected to contribute toward tuition, room, or board. This income threshold will increase to $100,000 beginning in 2023–24. Further, Stanford’s aid program will take into account the increase in tuition for current students receiving need-based financial aid; those whose family financial circumstances do not change can expect to pay the same amount they do this year, and possibly less for those with family incomes under $100,000.”

According to Stanford’s website, about two-thirds of students receive some form of financial aid. Even students whose families earn more than $150,000 may be awarded aid “on a sliding scale based on family finances.”

The Department of Education’s Integrated Postsecondary Education Data System shows that full-time freshmen from families with incomes over $110,000 paid an average of $42,108 a year, whereas those in the $75,001-to-$110,000 band paid $9,562 in the 2020–21 academic year, according to the most recent data available.

Bill Hall, co-founder and president of Applied Policy Research, which advises colleges on admissions, enrollment and economic forecasting, said that a 7 percent tuition increase is “extremely aggressive” compared to the advice he is giving clients. At the same time, Hall noted that the sharp spike likely won’t affect a large number of students or drive many applicants away.

Though it sounds steep, a 7 percent tuition increase isn’t much for high-income earners, who experts note are less price sensitive than many families struggling to pay for college. (At Stanford, fewer than 20 percent of undergraduates received Pell grants in the 2021–22 academic year, according to recent university data.)

In a sense, said Hall, Stanford is playing Robin Hood by using “extra income that the university will be making from the more affluent to provide even stronger support for poor students.”

David Feldman, an education economist at the College of William & Mary, offered a similar take, noting that Stanford is essentially “taxing the rich to subsidize the poor” with its tuition increase. Feldman also noted the concentration of wealthy families at Stanford, who can afford the hike.

Given Stanford’s acceptance rate, which in recent years has fallen below 5 percent, Feldman said it’s hard to believe that a few thousand dollars’ difference will drive the highest-income earners toward another institution. One possible negative, Feldman noted, is that low-income families who don’t understand tuition discounting as well as their high-income counterparts may be deterred from applying to Stanford, given the sticker shock associated with listed tuition prices. But over all, Feldman said, the tuition increase is a fairly low-risk move for Stanford.

More Price Hikes Coming

Experts expect that Stanford’s 7 percent jump will be an outlier, even as more institutions announce likely price hikes this fall.

They note that colleges and universities are juggling financial pressures on multiple fronts beyond inflation. The challenges they face include hiring and retention issues, demands for higher pay, slumping endowment returns for the most recent fiscal year, deferred maintenance costs, and the loss of generous federal relief money that flowed to colleges during the coronavirus pandemic.

“The real cost of college at most institutions has been declining over the past three years,” Feldman said. “Most schools have kept tuition relatively flat through COVID, so the real cost to students is declining, but the real costs to the schools are not. So there are a lot of pent-up needs.”

Those financial pressures inevitably will lead colleges to raise tuition for the 2023 academic year, though Hall suggests those forthcoming increases are likely to be in the 3 to 5 percent range.

“I do not think the spectacular figures that you find for outliers are going to become dominant. I watched our strongest institutions start out above my range of 3 to 5 percent, and work their way back under 5 percent. If I were to make a forecast right now, for the nonelite institutions, I would say you’re going to be approaching a 4 percent tuition increase” on average, Hall said.

While some colleges have frozen tuition, both Hall and Feldman are skeptical about that approach, suggesting that operating funds have to come from somewhere. One common example is Purdue University, which has famously frozen tuition for 12 consecutive years. At the same time, experts note that Purdue has recruited more out-of-state students, who pay higher tuition.

While Stanford is the latest to use recent inflation rates as a rationale for raising tuition, it isn’t the first. Other colleges cited inflation last summer when they raised tuition. For example, when Boston University raised tuition by 4.25 percent last year, President Robert Brown explained the move in a letter to campus noting that his “greatest immediate concern is the impact of inflation.”

At the time, the inflation rate was 8.3 percent over the prior 12 months, according to data from the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics. Inflation now stands at 6.4 percent, per recent BLS data, still much higher than the 2 percent inflation target set by the Federal Reserve.

While tuition is almost inevitably going up at many institutions, Feldman suggests that there is an understanding among consumers that may be advantageous to higher education leaders to help communicate those decisions. Consumers understand how rising costs affect their own budgets, Feldman said, meaning colleges have a natural explanation for increasing tuition prices.

And for Hall, who regularly works with colleges, that’s exactly the message many want to send.

“In the conversations I’ve had with chief financial officers, they’re saying, ‘I want to take advantage of the inflationary circumstances where people understand inflation and rising costs, but I don’t want to jump on a bandwagon that puts me in a position where they’re lumping me in with large oil companies making record profits,’” Hall said. “‘We’re not making record profits—we’re trying to make up for losses in the last few years. Most importantly, we’re trying to make up for the loss of a substantial amount of free federal money that came our way as COVID relief.’”