You have /5 articles left.

Sign up for a free account or log in.

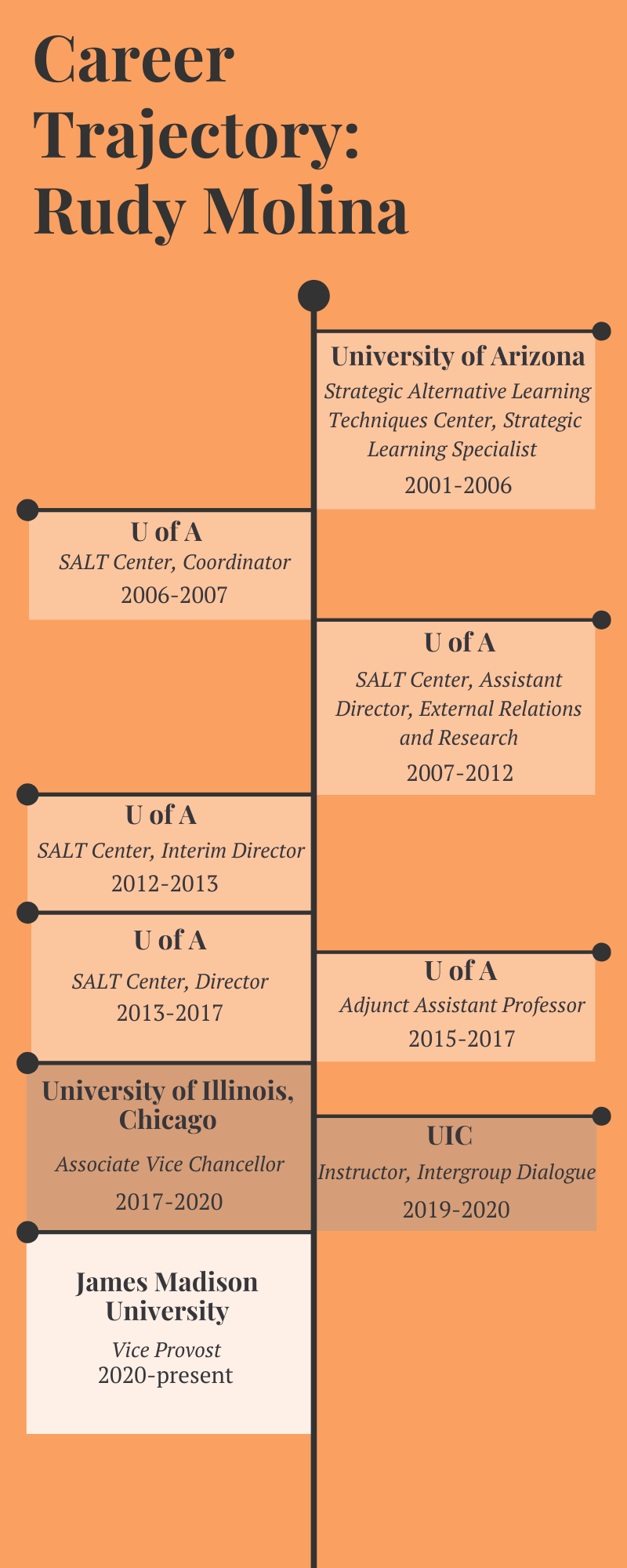

Growing up, Rudy Molina thought he was going to be a doctor. In fact, he found the idea of being a teacher a little insulting. But now, with decades of experience in teaching and higher education under his belt, he’s looking at new ways to shape the student academic experience, leading with equity and access in mind.

As vice provost of student academic success and enrollment management at James Madison University in Virginia, Molina approaches student success from a curricular perspective, focusing on student learning experiences and how educators can best support their students.

Molina spoke with Inside Higher Ed about his heart for students with disabilities, his goal-oriented mind-set in establishing solutions and his philosophy for student success.

Q: What led you to a career in higher education and, specifically, focused on student success?

A: In high school … I was identified as a good student, but not really a great student. You know, I had C’s and B’s, maybe an A sprinkled in there every once in a while, but really nothing phenomenal in middle school. But some teachers saw the potential in me, I guess, and by the time I got to high school, there was my AVID teacher, who turned to me after a few years working with her, and she said, “Rudy, you’re going to be a teacher.”

That was the first moment that education was planted in my mind.

The research I did as an undergraduate in bilingual education was kind of the next important thing. In my senior year, I wrote a paper that describes this—I thought—innovative thing: bilingual education and special education mixed into one. And even though I thought it was brilliant and a new idea, apparently there were many people who have been doing the research already. But I found it pretty interesting because it really showcased and spotlighted how children in the United States are being diagnosed with disabilities, even though they didn’t actually have a disability, and were put in special education.

Early on in my career, I worked for a program at the University of Arizona that supported college students with disabilities, and I found a great calling there because the mentorship that I had done in my undergraduate [years] with middle school students and similar experiences really helped me work one-on-one with college students. And I think from there on, I was in student affairs, and that position opened up the door to being a practitioner in higher education and really being able to make an impact on student’s’ lives.

Q: What is your role at James Madison University?

A: My official title is the vice provost of student academic success and enrollment management. I oversee the registrar, the learning center and the university advising and professional health advising at the university. We also work with the summer and winter sessions.

My role is really to build out partnerships and relationships with the deans, the academic colleges, the associate deans and then also the department chairs of each of those units.

Q: How does student success work in an academic division vary from that of a student affairs position?

A: There’s been a shift in higher education over the past 10 to 15 years, and that is student success work is increasingly being done not out of the vice president of student affairs’ [office] but shifting to the vice president of academic affairs or the provost office.

I had grown up professionally out of student affairs, and I was curious more and more what it would be like to do my work, but out of a provost office instead of student affairs. And I think one of the main challenges I face is, when I was looking at certain types of analyses, like DFW rates across the curriculum, as a student affairs professional, I was being told to stay in my lane and not do those analyses … and I think it was because there was a division, a line being drawn: “This work is being done in academic affairs, and this other work is being done in student affairs.”

I didn’t really understand why there needed to be a line if we’re looking at the whole student. And still, to this day, I observe those lines being drawn all the time, and perhaps I’m guilty of doing the same thing. But I think we need to find ways to blur those lines a lot more in a way that makes sense for the institution and the context of the institution.

Q: What inspires you in your work in student success, particularly in supporting students with disabilities?

A: I was diagnosed with an auditory processing disorder in the third grade, and my mom really found that I was having a hard time speaking and reading and doing math. In fact, I was struggling in most academic areas … I think she was really concerned, like, “How in the world is this kid gonna survive school if he can’t do some of these most basic things?”

I think she was really fearful … I wasn’t going to be able to achieve what she wanted for me and reach my full potential. So I was in special education, actually, from that point on. I was diagnosed with a disability and working with teachers and tutors and speech pathologists all the way through middle school and just received a lot of support that, as you can imagine, shaped the way I look at and see students. I knew that I struggled, and I really didn’t want other students to struggle in that way.

And, on top of that, if people were able to help me—like, really good teachers, really good tutors—and if I was able to benefit from those kinds of things, I really found inspiration and hope that, maybe I might be able to help a couple of students along the way. So that’s what actually drove me to study special education and also to become a learning specialist.

Q: How do you define student success, and how is that measured in the short and long term?

A: The obvious answer would be something along the lines of, here’s the academic outcomes, here’s the lifelong outcomes. And I don’t want to discount—those are really important, especially when you get into building out goals and stuff.

I really believe that we have to visualize where we want to go, like dream it, almost be able to see it already taking place. And I don’t think we do that enough in higher education. I think, if we were to actually start with a desired state, to be able to see it in action, and to visualize what it is that we’re pursuing as the first step, then I think we would probably set different types of goals.

In my career, I have found—and even the leaders that I have studied and worked under—this has not been the practice. It’s actually been, “What are we struggling with? Where are the gaps?” and “Let’s build out goals and action steps to close those gaps.” Which is great, but if we start there, then we’re … likely to close the gaps, but what if that wasn’t the ultimate goal? What if the ultimate goal was to help students achieve their full potential?

So maybe it’s the same objective, but a different approach and different way to start the equation.

Q: What’s example of a way you’ve worked from a place of goal visualization, rather than problem solving?

A: I’m part of the provost office, it was really important to establish the quality enhancement plan for the reaffirmation and accreditation process for the university. I was put on point to bring together four different research papers that we wrote internally and to come up with the project for the university over the next seven years.

There were four topics that came about—mental health; overall retention; diversity, equity and inclusion; and advising. And when they came in to be discussed and synthesized, the provost turned to me and said, “OK, we just need, within a short period of time, something that incorporates all of these.”

I proposed an early-alert concept that would incorporate the retention but also the equity gaps within the student population … We knew advising was going to be an important part of this, because the advising team, faculty and professional advisers were going to be part of this system … and finally, mental health and other types of engagement opportunities were going to be incorporated.

Here’s the problem: all of those are reactive type of things. We were going to close gaps, we were going to improve retention and we were going to address mental health and build out advising support, but we never took the time to visualize, “What is it that we want students to experience and feel first?”

In special education … we tend to look at a medical model, where the individual is broken and we need to fix that individual—whereas a different perspective might be, society might need to adjust a bit to the individual. And perhaps that’s what higher education needs to continue to do and develop out: [not] “How we are going to change our students, because they’re broken?” but “How are we going to change our systems to welcome and adjust so we can help them reach their full potential?” And I think that maybe is a guiding light and something that can be powerful as we move forward in the next generation of students.

Are you a higher ed leader with student success in your job title? Tell us what part of your story stands out.