You have /5 articles left.

Sign up for a free account or log in.

Caltech is expanding its admissions options beyond requiring calculus, chemistry and physics classes for entering students.

Among the thousands of applications to the California Institute of Technology each year, Ashley Pallie receives hundreds of panicked pleas from students with a particular problem.

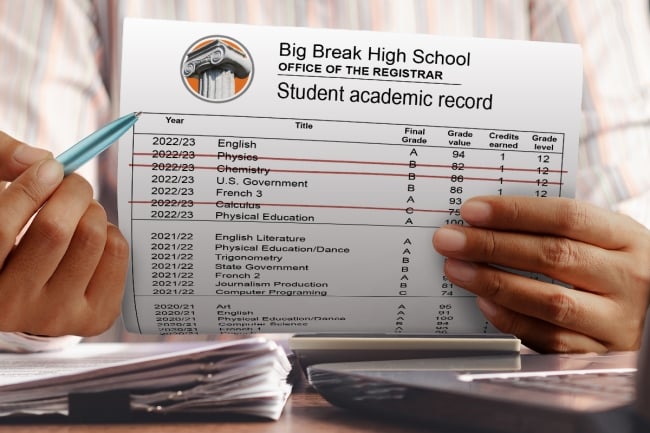

The worry isn’t low GPAs or a lack of extracurriculars. Instead, the applicants don’t have access to one of the three required high school STEM courses—physics, chemistry and calculus—needed to get into Caltech.

One student said their physics teacher quit, so they couldn’t take the course. Another said calculus wasn’t available in their high school or a nearby community college.

“You might have a brilliant biologist who’s done a ton of stuff but physics isn’t available to them,” said Pallie, Caltech’s executive director of undergraduate admissions. “They can take every bio class but say, ‘I don’t have access to physics and you’re telling me you can’t come to Caltech?’ and the answer used to be, ‘Unfortunately, yeah.’”

That changed this fall. Caltech announced it will allow substitutions for calculus, chemistry and physics classes.

It’s the latest in a growing effort by STEM-focused institutions to push for equity across racial and socioeconomic lines.

“Fundamentally, the problem is the same; the solution will vary,” said Rick Clark, executive director of undergraduate admissions at the Georgia Institute of Technology. “What [Caltech] has put their finger on is there’s huge holes where kids don’t have access. And what are we going to do about it and be a part of the solution going forward?”

While STEM classes and careers have risen in the general social consciousness, access challenges remain, according to Faith Savaiano, associate director of social innovation at the Federation of American Scientists. There’s growing demand to fill the STEM talent pipeline to fill jobs in science and tech industries. Simultaneously, there’s been a decline in the number of STEM teachers, especially in rural and low-income high schools.

“I think for a lot of schools across the country, there’s a big disparity in courses and [Advanced Placement] offerings,” Savaiano said. “It’s a place where the schools are have and have-nots.”

Caltech’s Substitution Switch-Up

The idea for Caltech’s expanded admissions offerings arose in February, when Pallie and her colleagues attended a conference and learned about the lack of access to calculus. They began to research and soon found the same inequities with chemistry and physics.

“If we’re talking about building something more equitable, you have to look at access,” Pallie said. “To tell people, ‘You’re a brilliant scientist but can’t come because your local high school doesn’t have this class’ didn’t seem fair with our equity mission.”

Caltech implemented the admissions expansion proposal in August. The expanded admissions requirements did not cost the school any money.

Instead of having calculus, physics and chemistry courses on a transcript, potential incoming students have three alternatives:

- A score of 5 on AP exams in AP Calculus AB, AP Calculus BC, AP Chemistry, AP Physics 1, AP Physics 2 or AP Physics C

- A score of 6 or 7 on the International Baccalaureate mathematics higher level; chemistry standard level or higher level; or physics standard or higher-level examinations.

- A certification from Schoolhouse.world in one of the following courses: AP/College Calculus BC; AP/College Chemistry; High School Physics–Next Generation Science Standards (NGSS)

The Schoolhouse certification option is intended to overcome the limited availability of the AP and IB tests, which are offered only at certain times of the year.

Caltech’s expansion option isn’t for all institutions, Pallie was quick to say. Caltech is a small university, with just over 1,000 undergraduates and roughly 235 students admitted each year.

It is also not targeted to help particular demographics or backgrounds, she said. Over the years, Pallie has heard from students hailing from rural communities to large urban school districts, all with the same complaint: lack of access. However, she did say there is potential to see an uptick in international students’ applications.

“Being a STEM school, we love data; there’s a real interest in seeing where interest comes from, the types of students—rural, suburbs—and what was in their application,” Pallie said. “I’m looking forward to January when we see what happens.”

Differing Approaches

Caltech’s change attracted national attention, but it is not the only STEM-focused institution attempting to overcome equity issues.

Virginia Polytechnic Institute and State University is focused on evaluating students on more of a case-by-case basis, which has been a particular focus this admissions cycle, according to Juan Espinoza, Virginia Tech’s director of undergraduate admissions.

To review admissions packets, the university has “readers” familiar with virtually all the Virginia high schools and aware of what courses are, and are not, offered, Espinoza said. For high schools the university is less familiar with—either across the country or state—more digging is involved. Transcripts are comprehensive at explaining the courses offered, or, Espinoza said, readers will simply call or email the school directly.

“We’re moving away from traditional sequences and check boxes and making sure we’re remaining accessible to everyone regardless of what courses might be offered,” he said. “But also making the best decision in a fair and equitable manner.”

The Massachusetts Institute of Technology turned toward digital offerings in 2012, just before the boom—and bust—of massive open online courses, or MOOCs, hit the mainstream. MIT’s version, now called MITx Online, allows students to take courses online for free.

It initially started as less of a pathway to MIT and more for the “public good,” according to Stu Schmill, MIT’s dean of admissions and student financial services. But the university found an influx of international applicants utilizing the courses as replacement offerings for what their high schools lacked. U.S. applicants, on the other hand, used the courses to supplement available high school options.

“I would be surprised if other schools don’t have something formally or informally just like this,” Schmill said. “I think every school needs to figure what’s appropriate for themselves, finding other pathways for students.”

Georgia Tech also offers expanded programming. It works with about 100 high schools across the state to offer distance education in advanced math. The program began in 2005 with 32 students and has now helped more than 1,000. Georgia Tech is considering expanding that to calculus and physics, plus more entry-level courses, like precalculus.

“It’s like rural medicine—getting teachers in those subject areas to want to choose to be in those communities is a challenge,” Clark said. “But it’s also an issue five miles from here, in metro Atlanta. It’s two problems—it’s getting the teacher or a critical mass of kids. Because public schools literally can’t offer a class to just nine kids.”

Going Beyond Class Alternatives

There’s a precarious balance between allowing students into an institution on a less traditional basis and also ensuring they are prepared for the rigorous course load. Nearly one-third of Georgia Tech’s new students, for example, are transfer students.

“We get a lot of students who have come out of the type of backgrounds where maybe they weren’t going to be able to compete in the first year, but [they] go somewhere else, get that base and then they come,” Clark said.

Clark and MIT’s Schmill both said they believe it’s not just enough to offer the alternatives. While students do take advantage of MIT’s offerings, for example, there needs to be a greater push from high schools and counselors to educate students on the options out there.

“I don’t think having the resources available is sufficient; it may be necessary, but it’s not sufficient,” Schmill said. “You need humans to mentor, identify students, help them through. These pathways are for some students who do have exceptional ability, who don’t have the resources where they are. But this won’t solve the equity issues around different resources in school. We need a bigger public policy.”

Both Savaiano and Julie Posselt, director of the Equity in Graduate Education Consortium, said federal support and funding within schools is necessary.

But at the university level, Posselt said, officials can begin by acknowledging—and dismantling—the admissions standards that have long reigned.

“It marks a change on the part of colleges and universities when they recognize the ‘requirements’ they’ve held are socially constructed rather than strictly necessary,” said Posselt, who also serves as an associate professor of education at the University of Southern California. “People sit up and take notice when Caltech makes a move. Whether others will follow suit remains to be seen, but it’s very important for leaders like Caltech to make courageous moves like this.”