You have /5 articles left.

Sign up for a free account or log in.

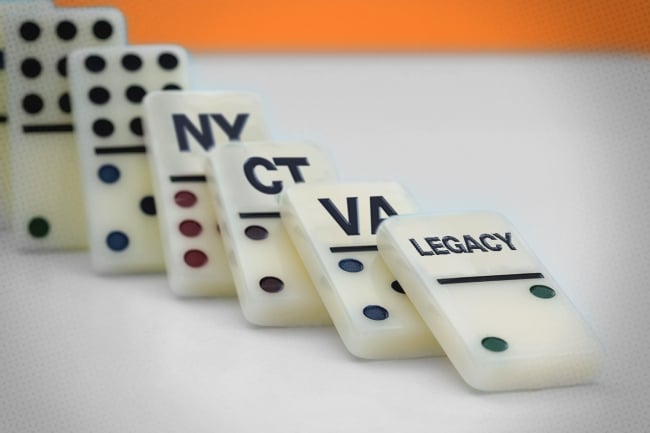

The Virginia state Senate unanimously passed a bill banning legacy preferences. Other states, like Connecticut and New York, are working on their own legislation.

Photo illustration by Justin Morrison/Inside Higher Ed | Baona/Getty Images

The Virginia state Senate unanimously passed a bill last Wednesday to ban legacy preferences in admissions at public universities. A House subcommittee approved it as well; the bill now awaits a full House vote next week before arriving on Governor Glenn Youngkin’s desk.

If the bill passes, Virginia will be the first state to ban legacy admissions in the post–affirmative action era. (Colorado banned the practice at public universities in 2021.) Critics and supporters alike say it could create a domino effect, emboldening lawmakers in other states and putting pressure on institutions to re-evaluate their own policies.

Schuyler VanValkenburg, the Democratic state senator who introduced the bill, predicted it would have bipartisan support; the state’s Republican attorney general has publicly decried the use of legacy preferences as antimeritocratic, and Youngkin has hinted that he plans to sign the bill if it passes the House.

But the unanimous vote was “a pleasant surprise,” VanValkenburg said, and the speed of the bill’s progress—the Senate Committee on Education and Health sent it to the floor less than a week before it passed—seems like a sign that the tide has turned decisively against legacy admits.

“Students for Fair Admissions changed everything … it really made this a fairness issue, which both sides of the aisle have rallied around,” he said. “We’ve seen much less opposition than I expected. Legacy is low-hanging fruit politically right now, as far as education reform goes.”

Admissions preferences for legacy applicants came under fire last summer after the Supreme Court struck down race-conscious admissions policies. Critics cited data showing that the colleges with the least socioeconomic diversity also tended to be those that gave heavier weight to whether applicants have a relative who attended the same college. The ruling breathed new life into the decades-old legislative battle over legacy preferences, reviving failed proposals in the U.S. Congress and legislatures in states such as California, Massachusetts and New York, among others.

In Virginia, focusing solely on public universities makes sense, VanValkenburg said; two of the most selective institutions in the state, the University of Virginia and William & Mary, are public.

They’re also among the select group of public universities that still consider legacy status in admissions decisions. Data suggest it can play a fairly important role: 15 percent of UVA’s student body last year were legacy admits, according to a university spokesperson; the share at William & Mary was 8 percent. Virginia Tech, another high-profile public state university, dropped its legacy policy last July.

UVA amended its policy last fall, expanding the definition of legacy to include applicants with “ancestors who labored at UVA”—strongly implying it could apply to descendants of the many enslaved people who were compelled to work on the campus before the Civil War. It was a solution that intrigued some and rankled others, but it ultimately helped preserve the university’s consideration of alumni relatives.

Cracks in the Ramparts

A bill to ban legacy preferences is under discussion in the Connecticut state Legislature as well—only this one would apply to both public and private institutions. The proposal, the details of which are currently being hashed out in the Senate Higher Education Committee, has already evoked bipartisan rumblings of support, said Derek Slap, a Democratic state senator and the chair of the higher ed committee.

Slap said that confining the ban to public institutions would be “basically meaningless” in Connecticut, where even the flagship University of Connecticut has long since dropped legacy preferences. But including private colleges means lawmakers are going up against institutions like Yale, which Slap described as “the 600-pound gorilla in the room.”

A similar Connecticut legacy ban bill failed to pass in 2022 after aggressive opposition from private colleges. This time around, Slap said, opposition has been much less concerted.

“Before the [Students for Fair Admissions] decision, this would have been a total slog to pass,” he said. “But colleges are backing off … they can see which way the wind is blowing.”

UVA deputy spokesperson Bethanie Glover said that while the university does not comment on pending legislation, officials stand by their decision to alter and expand the definition of legacy and are committed to doing “everything within our legal authority to recruit a student body that is both extraordinarily talented and richly diverse.”

A spokesperson for the UVA Alumni Association declined to comment on the record about the legislation. But VanValkenburg suggested that there’d been little, if any, lobbying against the bill on behalf of UVA or any other institution that would be affected by it.

Legislative proposals on legacy in other states have received similarly muted opposition since the affirmative action ban. Last July, New York’s Commission on Independent Colleges and Universities—the de facto lobbying group representing private New York institutions such as Columbia, Cornell and NYU—dropped its opposition to a bill in the state Legislature that would ban legacy preferences for public and private institutions.

Richard Kahlenberg, a lecturer at George Washington University’s school of public policy and longtime critic of legacy preferences, said the weakening pro-legacy stance seems to be a response to popular headwinds, and a recognition that affirmative action was, in many ways, a crucial bulwark in justifying the continuation of legacy preferences.

“As long as race-conscious admissions existed, there was a gentlemen’s agreement between institutions and civil rights orgs not to go after legacy. One essentially justified the other,” he said. “After the affirmative action ban, lobbying against what’s increasingly perceived as a civil rights issue is not a good look at all … If I were a university, I’d be nervous to be pressing against this even behind closed doors.”

A Frustrated Push Down a Slippery Slope

The old guard of legacy defenders is not entirely enfeebled, however.

Unlike New York’s higher ed lobbying group, the Connecticut Conference of Independent Colleges, or CCIC—which represents 15 of the state’s most selective private institutions, including those with large legacy populations like Yale University and Trinity College—is sticking to its guns.

“Our membership agrees that the determination to consider legacy or not should remain at the institutional level,” CCIC president Jennifer Widness wrote in an email to Inside Higher Ed. “State legislation banning legacy admissions will not move the needle on promoting equity and access in Connecticut. Policymakers should focus on investing in programs that promote opportunities for all students, like need-based financial aid.”

Angel Pérez, CEO of the National Association for College Admission Counseling, agreed that the issue of legacy preferences is one that institutions should sort out for themselves.

“I think this is a slippery slope, and I’m very concerned whenever state legislatures creep up on institutional autonomy,” Pérez said. “The Supreme Court decision definitely put us on that slope, and this feels like the next layer.”

But institutions have mostly avoided taking action on their own. The Supreme Court decision spurred widespread speculation that public pressure to end legacy preferences would lead many selective institutions to shed their policies. With a few notable exceptions—Wesleyan University, for example—and a smattering of half measures, like UVA’s amended definition of legacy, that wave has yet to crest.

“They have no track record of doing these kinds of things on their own,” Slap said, making a pointed exception for Wesleyan, which is in Connecticut. “Especially post-SFFA, that’s a really weak argument. And I think deep down, they know that.”

Slap said he’s pushing for a “sprint” to the governor’s desk, and he anticipates that the bill will move to the floor within a week or two. But even if the CCIC manages to stymie it again, he’s confident its ultimate success is inevitable.

“[The universities] are on the wrong side of history here,” he said. “Whether we pass a bill this session or next, this year or in five years, it’s going to happen. They have to decide whether to get on board willingly or not.”

Jill Orcutt, global lead for consulting at the American Association of Collegiate Registrars and Admissions Officers, said that while her organization doesn’t have a position one way or another on the bills, she would encourage policymakers to consider the institutional pressures that make legacy data useful at many colleges.

“Institutions’ ultimate goal is to admit qualified students who are likely to enroll, and for many colleges, legacy admits are more likely to commit,” she said.

Suzanne Clavet, director of news and media at William & Mary, said the data bear this out. Forty-four percent of admitted students who have legacy status at W&M end up enrolling, while 54 percent participate in an interview and 40 percent visit campus. That’s more than double the average rates for admitted students, which hover at around 18 percent in each category.

“Utilizing this data helps us achieve the targeted class size for enrolling cohorts,” she wrote in an email.

The antilegacy momentum appears to be building regardless. In November, U.S. senators Tim Kaine, a Democrat from Virginia, and Todd Young, a Republican from Indiana, introduced a bipartisan federal bill to ban legacy preferences nationwide.

“If Virginia passes this bill, that really ups the ante for federal legislation,” Kahlenberg said.