You have /5 articles left.

Sign up for a free account or log in.

FAFSA completion rates are trailing far behind previous years, on pace to decline by more than half a million students come June.

photo illustration by Justin Morrison/Inside Higher Ed | Getty Images

In a typical year at LEAD Academy High School in Nashville, a college prep–focused charter school where Kelly Pietkiewicz used to work as a counselor, about 80 percent of students fill out a Free Application for Federal Student Aid (FASFA).

This year, with only a few weeks until graduation, that number has dropped to 20 percent.

“It’s an actual nightmare,” said Pietkiewicz, who now serves as scholarship coordinator for the charity nonprofit Community Foundation of Middle Tennessee. “We’re still trying to get scholarships out to students, but most of the work I’m doing now is going to local high schools and helping their counselors answer questions about financial aid because they’re stretched so thin.”

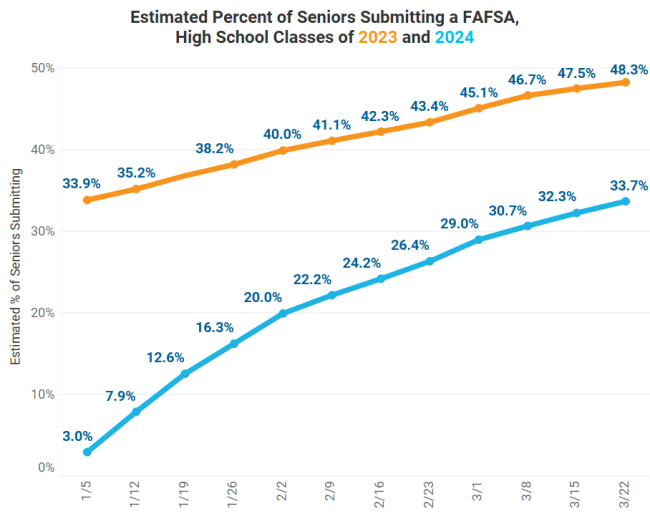

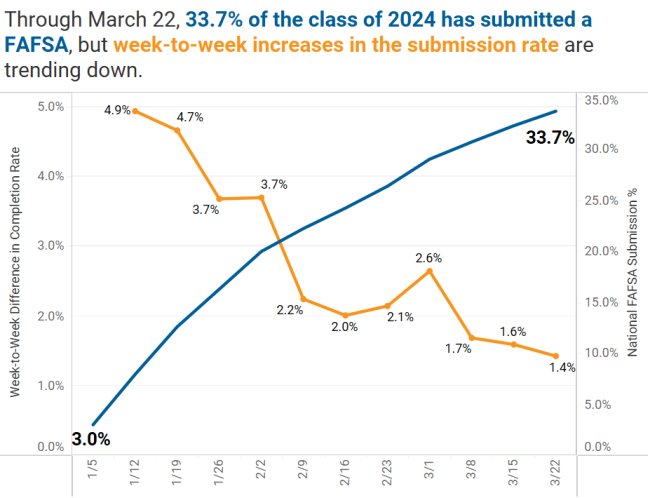

Nashville is no outlier. As of March 22, only 33.7 percent of high school seniors had completed a FAFSA, down 28.8 percent from last year, according to data from the National College Attainment Network (NCAN), which has been tracking completion rates throughout this tumultuous financial aid cycle. The network estimates that at the going rate, about half a million fewer students in the class of 2024 will submit a FAFSA compared to last year.

And that’s probably an optimistic estimate, said Bill DeBaun, NCAN’s senior director of data and strategic initiatives; if the pace of completion doesn’t pick up, the decline could be closer to 700,000 students. That could translate to up to a 4 percent drop in college-goers come fall, DeBaun said, which would be the largest enrollment drop since the COVID-19 pandemic—and one that’s likely to be made up primarily of low-income and first-generation students.

National College Attainment Network

State leaders, advocacy organizations and higher ed institutions are rallying students to submit their FAFSAs as fast as possible, and high schools are doing all they can to answer the call. But with counselors stretched thin and less than two months until high school graduation season, time is running out.

“I’ve been sounding the alarm about this for months,” said Angel Pérez, president of the National Association of College Admissions Counselors. “We’ve already lost so many students during COVID; losing another half million to the FAFSA has grave implications.”

Jaclyn Piñero, national CEO of uAspire, a nonprofit that works to boost college-going among underserved populations, said she’s trying to stay optimistic. But as issues with the form remain unsolved and Education Department errors pile up, she’s seen a lot of burnout, too.

“We need to keep beating the drum to get FAFSA completion up. But it’s tiring and taxing for counselors who are already overworked, and students aren’t feeling like the system is there for them,” she said. “If I’m being honest, I don’t think we’re going to recover to anywhere near last year’s numbers. And we’ll probably continue to see maybe even a double-digit drop in enrollment, mainly from low-income and first-gen students of color.”

Crisis Begets Crisis

Some states have struggled more than others to boost FAFSA completion—especially those with high average student-to-counselor ratios.

Southern states’ completion rates have fallen the furthest on average. Sean Kennedy, president of the Southern Association for College Admission Counseling, a professional association for college counselors covering the Southeastern United States, said the completion rate is down by at least 25 percent in every state in his territory. West Virginia and Mississippi are down 35 percent year-over-year.

Tennessee high schools have an average of one counselor for every 420 students, far higher than the American School Counselor Association’s recommended ratio of 250-to-1. Despite that disadvantage, the state worked hard for years to get FAFSA completion up, largely by making it an eligibility requirement for the Tennessee Promise state scholarship program. This time last year, Tennessee boasted the highest completion rate in the country, with nearly 80 percent of students filling out the form by mid-April.

This year, completion is down to 40 percent of high school students, a decline of 43.7 points—the largest year-over-year drop of any state. State education leaders are urging students to get their forms in soon—this past week was “Finish the FAFSA Week” in Tennessee—but it may be too late to make up more than a small slice of the decline.

Pietkiewicz blames the nosedive on deep frustration among families over the rollout of the new FAFSA. Her organization removed FAFSA completion as a requirement to qualify for scholarships last summer, when delays in the new form’s launch first raised concerns. But most students who need aid to afford college must fill it out anyway, and Pietkiewicz worries they won’t do so in time.

The consequences of the plummeting completion rate are already becoming clear. A former Community Foundation scholarship recipient who Pietkiewicz has stayed in touch with said her younger sister decided not to go to college this year because of her frustration with the FAFSA.

“She’s not the only one,” Pietkiewicz said. “It’s happening all over the state, where students and families are looking at the chaos and calculating the time and energy they need to invest and concluding that it’s just not worth it.”

Losing Steam

In recent weeks, progress has actually slowed rather than picked up. At the end of February, FAFSA completion was going up by almost 3 percent per week, according to data NCAN provided. A month later, that pace had slowed to 1.4 percent, and it appears unlikely to pick up without some kind of intervention.

“We expect a long tail for FAFSA submission into the summer, but high schools won’t be open to help students by then,” DeBaun said. “We need to make this happen now, while high school seniors are still an invested, captive audience. We’re running out of road.”

Kennedy believes the lack of progress in making up for lost time comes from a kind of FAFSA fatigue: the longer it takes to get over the obstacles to completion, the harder it is for students and families to see it through to the end.

“Complexity creates barriers, barriers erode resilience,” he wrote in an email to Inside Higher Ed. “With no resilience, students may stop trying and that is the tragedy.”

Students with noncitizen parents have had perhaps the greatest difficulties completing the form. When the new FAFSA launched in January, a technical glitch did not allow students to progress without entering a parent’s social security number. Four months later, the Education Department has yet to fully fix the issue, though officials have introduced a workaround. Piñero said students with undocumented parents are fast losing patience. She believes those students represent a large portion of those who’ve given up on the form.

NCAN’s data bears this out. In California, where close to 11 percent of the population is composed of mixed-status families, FAFSA completion has dropped by 115,860 students, or 36.6 percent—second only to Tennessee in the extent of its decline. Texas and Nevada, states with similarly high proportions of mixed-status residents, are also near the bottom of the list, with over 34 percent declines each.

“For some families, often white, middle-class ones, this FAFSA form has been their easiest to fill ever; it’s the department and college side that’s been complicated,” Piñero said. “But many of the most vulnerable students have really had to fight to complete it. And they just don’t have the energy to keep fighting on every front like this.”

‘A Long Tail’

Perez said the completion crisis could have as serious an impact on higher ed enrollments—and colleges’ finances—as the pandemic did.

“It’s just as bad as Covid,” Perez said. “Maybe worse. Because the difference between Covid and now is, there was an influx of funding to offset the impact of the pandemic. I’m not seeing any talk about that now.”

Financial assistance from the federal government could help. Because of the many delays in the FAFSA rollout, high school students will likely be trying to fill out FAFSAs into the summer months. Piñero said that districts like Los Angeles Unified have told her they want to make counselors and other resources available for those students, but don’t have the money to pay them past the end of the school year.

That’s where federal funding could supplement district budgets—and considering the U.S. Education Department is to blame for the FAFSA mess, Piñero thinks it’s a more than reasonable request.

“Really, this is on the Federal Student Aid office. We want to be partners and support high schools however we can, but students and counselors can’t just work around the challenges,” she said. “Unless we all wake up tomorrow and the FAFSA is completely fixed, and ISIRs are being processed at a clip of 20,000 a day, we will have significant enrollment declines.”

Regardless of support from state and federal actors, Pietkiewicz said the completion crisis belies a more serious, potentially longer-standing issue: the loss of trust in the federal financial aid system. At a time when the cost of college is eating away at Americans’ confidence in the value of a postsecondary education, it could sour the public’s outlook on college for years to come.

“The damage done to the foundational trust in FAFSA and in the financial aid system in general won’t just impact this class,” Pietkiewicz said. “It will trickle down. I’m afraid this is going to have a long tail, and we’re only just seeing the effects.”