You have /5 articles left.

Sign up for a free account or log in.

Three-quarters of UT Austin students are admitted automatically. For the rest, it’s an uphill battle.

Photo illustration by Justin Morrison/Inside Higher Ed | Getty Images | Liam Knox

Brandie Cleaver, the college counselor at Stephen F. Austin High School, has a metaphor she likes to use when talking to students about applying to the University of Texas at Austin. As with most of her teaching analogies, this one is about dessert—specifically, pie.

“Mrs. Cleaver loves pie,” she says. “Coconut and chocolate are my favorites, but UT Austin pie is OK, too.”

She’s drawing a pie chart on the whiteboard in her office, which seems to have an open-door policy: About a dozen students sit around the large room in desks and on colorful chairs, working on homework or applications under walls plastered with college pennants. One pipes up from a bean bag: “The pie thing again?”

It’s a familiar analogy for Cleaver’s students because most of them have the state flagship, whose campus is just uptown, on their short list of prospective colleges, and she often has to explain just how slim their chances of admission really are. The pie conceit helps a complicated state policy issue go down a bit easier for 17- and 18-year-olds, though they may not love the taste.

“This big chunk of the pie is already eaten by the time you apply; if you’re not in the top of your class, you’re wrestling with everyone else for this other little slice,” Cleaver explains, wielding a dry-erase marker like a cake knife. “If you’re a junior or senior not in [the top 6 percent of your class] and you’ve only got Austin on your list of schools, it’s time to think of some backups, because there’s just not enough pie to go around.”

Brandie Cleaver in her office at Austin High School. Half a dozen camera-shy students are just out of frame.

Liam Knox/Inside Higher Ed

Getting into UT Austin is no sweat for Texas residents who graduate in the top 6 percent of their high school class. In accordance with a nearly 30-year-old state policy—which, until last year, was the only one of its kind in the country—all those students have to do is apply and they’ll be automatically admitted. The law mandates that at least 75 percent of UT Austin’s admits come from this pool.

But for students who don’t make the cut, getting into UT Austin has become about as difficult as getting into Dartmouth.

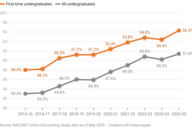

It doesn’t help that the university has, since the automatic admission policy was implemented in 1997, morphed from a solid public flagship and football powerhouse to an internationally renowned “public Ivy.” And it only keeps getting more selective: Last year 72,885 students applied to UT Austin, almost double the number in 2013. This fall it smashed that record by 25 percent, receiving more than 90,000 applications between August and December. Out-of-state applicants alone rose by 48 percent this year.

UT Austin admitted 9,210 first-years this fall, its second-largest incoming class ever. Of those, about 7,000 were admitted automatically. State law limits out-of-state students to 10 percent of the university’s undergraduate population, which totals about 42,000; in 2022, the latest available national data, 8 percent of the incoming class were from out of state. If the proportions are roughly the same this fall, that would leave just 1,200 spots for Texans who are ineligible for automatic admission.

The flagship has long grappled with how best to balance surging interest with state-mandated admissions quotas. While other public universities in Texas must admit the top 10 percent of each high school class, Austin was given a special exemption in 2009 to determine its own threshold, which officials recognized would have to be flexible as the applicant pool ballooned. In 2017, they lowered it to the top 6 percent; this September they announced it would drop again, to the top 5 percent, starting with the high school Class of 2026.

We’re both a very selective institution and, in some ways, an open-access school.”

—Miguel Wasielewski, director of admissions

Miguel Wasielewski, UT Austin’s longtime director of admissions, said the automatic admission policy has a profound effect on how his team shapes incoming classes.

“When [state lawmakers] wrote the legislation, they couldn’t foresee this explosion in our popularity,” he said, “It means we’re both a very competitive institution and, in some ways, an open-access school. The number of automatic-admit applications really drives the rest of the class.”

Kevin Martin, a private college counselor and a former UT Austin admissions officer, said the state’s auto-admit policy has affected more than just the internal admissions process. It’s also transformed how Texas students from wealthy, high-achieving high schools view the school, he said, fostering a cutthroat admissions environment that looks like a locally contained version of Ivy League competition.

“When I worked for [UT Austin] 12 years ago, it wasn’t really a desirable university for the top 1 and 2 percent of students … but in the past decade, applicant numbers have skyrocketed significantly from those top suburban or private high schools,” he said. “One of my roles back in the day was to try and encourage those top kids at the top schools to even apply, let alone enroll. Now, their best students are competing to get in.”

Cleaver said that can be a difficult wake-up call for parents and students at Austin High.

“I had a father recently tell me, ‘Mrs. Cleaver, I like pie, but after this conversation, I don’t think I’ll be able to eat it for a while,’” she said.

A Diversity Policy Model?

In 1996 the state’s Supreme Court banned affirmative action at public colleges in Hopwood v. Texas, and the implications for institutional diversity were massive. UT Austin was particularly affected: The following year its enrollment of Hispanic first-years dropped 15 percent and Black students by 25 percent. In response to that decline, Texas lawmakers implemented its automatic admissions policy, mandating that the top 10 percent of each high school’s graduating class across the state would be guaranteed admission to any public university.

If the top students from the most underresourced high schools in the state had a sure spot at a four-year college, the thinking went, it would be good for college access and institutional diversity—racial, but also geographic and socioeconomic. The plan was a boon for college access statewide; even though the Hopwood decision was overturned in 2003 by the U.S. Supreme Court in Grutter v. Bollinger, the policy was popular enough that Texas kept it around.

Its impact on racial diversity was more muted at UT Austin, which never recovered its pre-Hopwood diversity levels. But there’s evidence the plan has helped the university maintain its diversity since: A National Bureau of Economic Research study found that socioeconomically disadvantaged students were 14 percent more likely to attend UT Austin or Texas A&M—the other state flagship—after the plan’s implementation than before. And this fall, UT Austin was one of the few highly selective institutions whose share of Black and Hispanic incoming students remained stable despite the Supreme Court’s affirmative action ban.

For decades Texas’s policy was unique, but now the 10 percent plan, as it’s colloquially known, has new converts. Tennessee adopted its own guaranteed admission rule last September, and the State University of New York system announced it would do the same starting next fall.

Wasielewski, who was named senior vice provost of enrollment in September, said Tennessee state officials reached out to him for consultation on their decision even before the Supreme Court decision was handed down. Interest from other university and state leaders has been steady if less official. He gives each of them the same endorsement of the plan, along with some advice: Figuring out how to make it an effective college access tool, and how to manage families’ reactions to the change in admissions, takes time. And supporting those new students takes money.

“The challenge for other states and institutions is that it takes years to communicate all of this with the local communities,” he said. “And if you have a program that is designed to get more low-income students to the university, that’s naturally going to increase the amount of financial aid you have to have. If you don’t change those resources, then you’re going to water down the financial aid to everyone.”

UT Austin admissions director Miguel Wasielewski, left, in his office.

University of Texas at Austin

Homegrown Resentment

Mickey Saloma, the head of college counseling at the private John Paul II High School outside Dallas, has been working in Texas admissions for about as long as the 10 percent plan has been in place. A former president of the Texas Association of College Admission Counselors, he’s been an admissions officer at Texas A&M and Southern Methodist University, as well as a college counselor at private schools like John Paul II and inner-city public schools like Thomas Jefferson in Dallas.

He said the main benefit of the state’s auto-admit policy is that it gives poor, often minority students who otherwise wouldn’t have thought to apply to schools like Texas A&M and UT Austin a ticket to a world-class education.

“I had a student once who got into UT automatically who would never have had a chance otherwise because her SAT score was so low,” Saloma said. “She graduated in four years and was very successful. That was life-changing for her.”

When someone else gets something we want, people have a tendency to see it as zero-sum.”

—Kevin Martin, former admissions officer

But one student’s opportunity can be perceived as coming at another student’s detriment, as years of debate over affirmative action showed. Martin, who wrote a guidebook on UT Austin admissions, said the auto-admit policy has led to growing frustration from wealthy suburban families whose children don’t get in.

“I’ve had to tell a lot of angry parents that they’re just going to have to get real with going to A&M, UT Dallas or University of Houston,” he said. “I would say I’m having those conversations a lot more in the last couple of years than ever before.”

Despite the policy’s technical race neutrality, Martin said those grievances often take on a distinct racial valence. “When someone else gets something we want, people have a tendency to see it as zero-sum; that’s especially true if that other person is from a different background,” he said. “As soon as that happens, there’s a lot of ‘Oh, these Black and Brown students are taking a spot away from my precious’—usually white or Asian—‘child.’”

Yvonne Espinoza, a former high school counselor who now runs a private college consulting business in Austin, has a different issue with the 10 percent plan. She said a policy expanding access is only meaningful when paired with a robust support system for low-income and first-generation students, many of whom have to work to support their families or suffer from housing and food insecurity. The university hasn’t done enough for them, she believes.

“The plan doesn’t include components that these students need to actually matriculate and then successfully and graduate and thrive while there,” she said. “How would students even start to navigate that process or understand what support is available to them once they get there?”

Flags flying on UT Austin’s campus, and the statehouse just across town.

Liam Knox/Inside Higher Ed

Around 75 percent of UT Austin students graduate within four years; the percentage drops to 66 percent for first-generation students and 67.5 percent for those eligible for Pell Grants.

Wasielewski said the university has made concerted efforts to support its underrepresented students financially and academically. Since 2019 UT Austin has waived tuition for students from families making less than $65,000 a year; just last month, the UT system announced it would raise that threshold to $100,000 for all of its institutions.

The calculation other states should make when considering an auto-admit plan, Wasielewski said, is how much they are willing to invest in their new students.

“A plan that says we want to make sure everybody has at least some opportunity to attend a great institution, I think that’s applicable across the nation,” Wasielewski said. “But every institution is different, and their challenges will differ based upon the popularity of the institution and where they’re able to commit resources.”

A Cutthroat Competition

Austin High is one of the oldest public schools in Texas, and its student-body diversity is fairly typical: A little more than half of its students are white and 36 percent are Hispanic; Black students make up about 5 percent of the population.

Austin High doesn’t have the same college-prep resources as its private and suburban counterparts. Cleaver is the only college counselor for 2,700 students. When she arrived three years ago, the number of students in a given year who were admitted to UT Austin—outside of the top 6 percent—hovered in the mid- to high teens.

Stephen F. Austin High School in south Austin.

Liam Knox/Inside Higher Ed

Cleaver said that was because students didn’t understand that getting into Austin was now, in many cases, harder than getting into Rice University, technically the most selective institution in Texas. She brought in a new approach that’s usually reserved for those with elite private college ambitions: maximizing students’ honors and AP courses, applying early action and generally committing to a hypercompetitive process. Since she began encouraging those changes, the number of Austin High students admitted to UT Austin has doubled.

But even the most hardworking students who fall out of the auto-admit threshold face an uphill battle once their application reaches the UT Austin admissions office. While Wasielewski lauded the auto-admit policy’s effects on diversity and access, he said it can be a challenge to find room for promising applicants ineligible for automatic admission while also controlling the university’s growth.

“We want to make sure that we have room for the artist, for the nurse and the architect. We want to have room to admit students outside of just that percentage, because there’s other things we have to look for in this holistic review process,” he said. “But we also have to be really thoughtful about responsible growth … other institutions keep raising their enrollment, and it just gets out of control to the point where students don’t have a quality experience.”

UT Austin’s enrollment has increased by 5 percent since 2019, according to state data, which comes out to around 2,000 additional students in all—despite yearly applications rising by nearly 40,000 over the past five years.

If you want to be a Longhorn, you’re going to have to sweat.”

—Mickey Saloma, head of college counseling, John Paul II High School

Saloma said that while he feels the auto-admit plan has been a net positive for Texas college access, he worries about the narrowing pathways to admission at places like UT Austin for promising students whose GPAs fall short of the cutoff.

“Every year I have students who say, ‘UT or bust.’ But that bubble of certainty bursts, even for some really promising kids,” he said. “Some parents are livid, but you have to manage expectations from the beginning. I tell them, ‘if you want to be a Longhorn, you’re going to have to sweat.’”

That can come as a shock to many families. When he emailed parents in his weekly newsletter about UT Austin’s huge leap in applications this fall, one wrote back, “When my grandkids apply, will the acceptance rate be one percent?”

Between the surge in out-of-state interest and growing migration to Texas from states like California, Saloma said that’s not too far-fetched a prediction.

“A lot of parents remember a time when if you didn’t get into UT Austin, you could take classes for a summer and be pretty much assured a spot,” he said. “Now nothing could be further from the truth. And this is just the beginning of how competitive Austin is going to get.”