You have /5 articles left.

Sign up for a free account or log in.

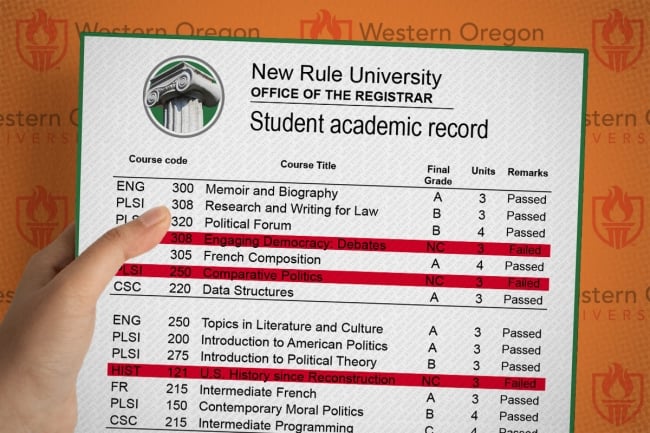

Western Oregon students will begin to see no-credit marks on their transcripts if they fail to earn a C or higher starting fall 2024.

Photo illustration by Justin Morrison/Inside Higher Ed | Western Oregon University

Faculty and administrators at Western Oregon University are aiming to increase student retention rates and foster academic equity by changing the university’s grading system.

The small regional institution, located an hour south of Portland, recently announced that starting this fall, its grading scale will no longer include D’s and F’s. It will instead use “no credit,” or NC, for students who fail courses. The new mark will not affect students’ grade point averages, but they will not receive credit and will have to retake the course to meet their degree requirements.

D’s and F’s on a transcript historically represented a student’s inability to meet a course’s learning objectives and often dramatically lowered their grade point averages, a performance metric heavily weighed by graduate school admissions officers and sometimes even considered by employers.

Some higher ed observers wonder if the change is providing an academic cushion, or an easy out, for students who either have fallen behind, lack the necessary skills or academic grounding, or are not putting in the effort needed to pass a course. They also note that banishing D’s and F’s could contribute to the existing grade inflation problem in higher ed.

Jose Coll, Western Oregon’s provost, argues that the university’s new grading model actually does the opposite.

“In no way, shape or form as a provost have I asked our faculty to lower the standards of the courses,” he said. “If anything, now what it will do is increase rigor, because students are required to earn a D or better in any of their courses. No longer can a student move forward with a D-minus.”

Western Oregon is among a growing wave of colleges and universities that are exploring or have already implemented alternative grading systems. Some institutions, including Brown University, have used alternative grading structures for years—in Brown’s case, since 1969. Other institutions, including the University of California, Irvine, have not implemented a universal policy but are actively informing and encouraging instructors to implement alternative grading models voluntarily.

But not all higher education experts support the trend. Some academics and consultants argue that while the new system has good intentions, it may inadvertently erode the rigor of a college degree and cheapen its value.

The Psychological Effect of Grades

Discussions of a new grading system started this past summer as Coll looked at the student retention rates at Western Oregon, at peer regional colleges and across the country. The numbers were dismal. The university’s data showed that over 65 percent of freshmen who had stopped out in the past five years had earned an F in their first quarter.

According to the National Student Clearinghouse Research Center, the population of individuals with some credit and no degree is particularly high in Oregon. For every 1,000 undergraduates enrolled in the 2021–22 academic year, there were 3,967 Oregon residents who stopped out before completing their college programs. The only state with a higher rate was Alaska, which had 5,357 residents who’d left college without earning credentials per every 1,000 undergrads.

Higher education leaders across the country are wrestling with the fact that about 40.4 million people, or 12 percent of Americans, have some college credit but didn’t earn a degree or certificate.

“I do not want to contribute to the 40 million,” Coll said.

He initiated research shortly after he was appointed provost in July to pinpoint particular factors that were causing Western students to stop out—and the psychological influence of grade performance proved to be a key culprit.

Compared to the 65 percent of freshmen who earned an F in the first quarter of the academic year and stopped out, only 17 percent of students who failed a class during the COVID pandemic but were allowed to opt for a “satisfactory” or “no credit” mark stopped out.

“It didn’t send the same psychological signal of a failure,” Coll said. “It doesn’t have the same impact on their overall GPA. It’s salvageable and they can continue to move forward.”

After a series of meetings with the Faculty Senate to discuss changing the grading structure, Western Oregon’s administrators decided to make the no-credit model a campuswide practice. Coll said they saw it as an “opportunity to do what was best for students” and eliminate some barriers, particularly for first-generation and returning adult learners. The end goal is to raise overall retention to 80 percent.

“This policy aligns to our commitment for student success and to evaluate students based on their strengths and their ability to achieve a specific goal … versus this kind of historical fixation with either you do or don’t belong—have you failed a course or not?” he said.

Inadvertent Consequences

Not all academics are as confident in the model as Coll. Mark Horowitz, an associate professor of sociology at Seton Hall University in New Jersey, believes there is merit in the growing focus on student success, but he also worries that as the desire to maximize retention and degree attainment grows, the definition of success will be watered down.

“I’m worried that the degree will no longer signal competence or grit … and then what will it really be?” he said.

Horowitz emphasized he had no doubt in the “good faith” and “compassion” of individual policy changes like such as Western Oregon’s, but he said he fears the downsides in the larger context of higher ed.

“I’m not advocating for faculty to be hard-nosed … I’m not even suggesting that the old model of those [weed-out] classes is necessarily appropriate. But I am worried about where we’re going,” he said. “In an extreme case, you could put a degree in a vending machine. And if success is defined as getting the degree and it’s not focused on the process of getting there—that would be seen as high student success.”

Horowitz, his Seton Hall colleague Anthony L. Haynor and Kenneth Kickham of the University of Central Oklahoma quantified these doubts in a 2023 study titled “‘Undeserved’ Grades or ‘Underserved’ Students?” Their survey found that 47 percent of faculty respondents believed academic standards have declined in recent years, 37 percent admitted to routinely inflating grades and 33 percent admitted to having reduced the rigor of their courses.

Michael Poliakoff, president and CEO of the American Council of Trustees and Alumni, believes Western Oregon’s is “one of a number of bad policies” that reflect a “state of standards dysphoria” in higher education. He noted that ACTA has heard a growing lack of confidence in college transcripts from Fortune 500 employers.

“Colleges need to go back to grading standards that are clear and that really indicate the level of achievement of their graduates,” he said. Increasing degree attainment “is not equity if it’s a ticket to nowhere.

“The equity would be to set real standards and to ensure that when students come they get the kind of support system they need to meet those standards,” Poliakoff added. “That’s harder work than simply shaving off the bottom rungs of the grades that students get.”

Coll responds to such critiques by explaining that although a no-credit mark will not alter the student’s GPA, their transcript will clearly show that they did not pass the course. Employers will also be able to see whether the student opted to retake the course and achieve a higher grade or substitute it with a different option—both of which indicate academic resilience in different ways.

“It’s gonna be extremely transparent,” Coll said.

But Horowitz said it is unrealistic to expect evaluators to go through each applicant’s transcript with a fine-tooth comb and look at the “microprocess” of obtaining a degree instead of having a traditional metric like GPA.

Others Take Similar Approach

Megan W. Linos, director of digital and online teaching at the University of California, Irvine, said although her institution hasn’t adopted a universal policy, as it prioritizes academic freedom, administrators regularly promote new grading models and course structures that allow students to customize the learning experience to their own needs. “Equitable grading practices are urgently needed,” Linos said. “Not only because we really want to promote a culture of diversity, equity and inclusion and accessibility in the classroom, but we also found that oftentimes the standard grading system doesn’t support students throughout the learning process.”

At UC Irvine, in addition to allowing professors to offer a pass-fail or no-credit option, some faculty members are implementing what is known as specifications grading. Under this course structure, professors outline a list of learning objectives that students must achieve by the end of the course. A-through-F grades remain, but students have the flexibility to decide how much time to dedicate to each objective and to repeat assessments in areas where they’ve struggled.

Like Colls, Linos doesn’t see these alternate models as less rigorous; rather, she argues that they are more supportive and promote success.

“The traditional grading style is really focused on evaluation instead of teaching and scaffolding,” she said. “When you talk about a model like specifications grading or a no-credit option, it empowers students to have a choice in how they would like to learn.”