You have /5 articles left.

Sign up for a free account or log in.

Senate Bill 1477 has already passed the Arizona Senate and the House Education Committee.

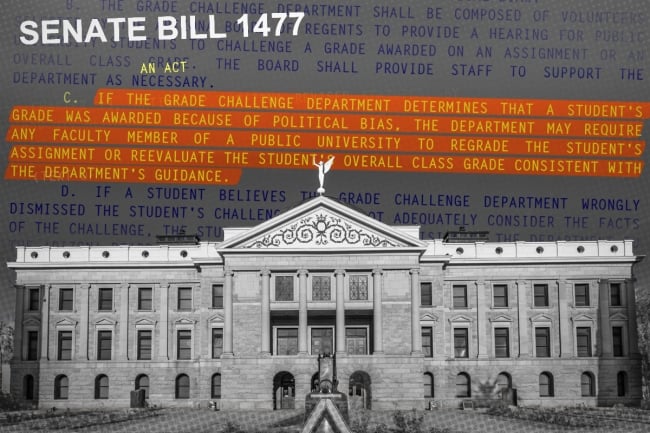

Republican lawmakers in Arizona have proposed creating a “grade challenge department,” to which public university students could complain that their professors gave them low grades because of political bias.

Senate Bill 1477, which is only five paragraphs long, says that if this new department concluded there was political bias, it could “require any faculty member of a public university to regrade the student’s assignment or reevaluate the student’s overall class grade.” Students could only allege political bias, not racial, religious or other possible sources of bias. The bill doesn’t define what political bias means.

Students who lose their cases before the department would be allowed to appeal to the Arizona Board of Regents. But the bill contains no appeal right for the faculty member whose grade could be overridden.

The legislation passed the state Senate Feb. 22 in a 16 to 12 party-line vote with two Democratic members not voting. Last week, House education committee members passed it 4 to 3 in another party-line vote, with a couple of Republicans and a Democrat not voting.

The margins matter. If the full House of Representatives passes the bill, it will head to Democratic governor Katie Hobbs. If she vetoes it, the state constitution says at least two-thirds of lawmakers in each chamber would have to vote to overturn that veto to make the bill law. The governor’s office didn’t return Inside Higher Ed’s requests for comment.

The bill “seems to be deeply problematic; it assigns to the Board of Regents powers that it really should have delegated to faculty,” said Mark Criley, a senior program officer for the American Association of University Professors’ Department of Academic Freedom, Tenure, and Governance. A faculty member’s right to assign the grades he or she believes a student deserves is considered a pillar of academic freedom. The bill doesn’t say whether the faculty member who gave the initial grade would be the one charged with giving the new grade.

Anthony Kern, the Republican senator who introduced the bill, didn’t return Inside Higher Ed’s requests for comment. He briefly spoke on the Senate floor Feb. 22, in the midst of senators’ vote on his bill.

“It’s a due process issue,” Kern said. “A lot of students that I met with at ASU [Arizona State University], they do not feel they can debate issues according to their politics or according to what they believe because they’re afraid their grades are going to be lowered.”

Kern’s bill may be a continuation of fallout from a February 2023 event on ASU’s campus that featured Charlie Kirk, Dennis Prager and Robert Kiyosaki. Kirk founded the Phoenix-headquartered conservative group Turning Point USA; Prager is a conservative talk show host who founded the PragerU video website; and Kiyosaki wrote Rich Dad Poor Dad and co-authored two books with former president Donald Trump. The event was billed as being about “Health, Wealth and Happiness.”

Some students and faculty members objected to it—the Arizona Republic reported that over 30 faculty members signed a letter saying that Kirk and Prager in particular attacked women, minorities and LGBTQ+ people—but the event still took place. However, Ann Atkinson, then-executive director of ASU’s T. W. Lewis Center for Personal Development, wrote in The Wall Street Journal in June that she was being fired and her center was being closed for organizing the panel.

A university spokesperson replied that Atkinson’s job would no longer exist because the namesake donor, Tom Lewis, ended his donation. But Atkinson said she had come forward with new donor funding conditioned on maintaining Lewis’s intent—the center taught, among other things, “traditional” American “values of hard work, personal responsibility, civic duty, faith, family and community service,” Atkinson said—and ASU rejected her effort.

Tempe-based KJZZ reported that state lawmakers, in response to Atkinson’s allegations, formed a committee “on Freedom of Expression at Arizona’s Public Universities.” Kern was co-chair. In November, Republicans said they wanted to cut ASU’s funding for allegedly discouraging conservative speech at that February 2023 event and another one, KJZZ reported.

“These Marxist professors that teach queer theory and anti-American garbage—they get away with this stuff, because nothing is done to them and it’s under the guise and smoke and mirror of free speech,” Kern said.

During last week’s House education committee meeting, Rachel Jones, a Republican member, referenced students who spoke to the committee on free expression, the Arizona Mirror reported. Jones didn’t respond to Inside Higher Ed’s requests for comment.

“Conservative students are feeling very silenced on their campuses,” Jones said, according to a video of the committee meeting. She said that “some of these students, to my understanding, are feeling the need to lie about their political beliefs so that they get good grades.”

A Process Already in Place

The Arizona Board of Regents—which oversees the massive Arizona State University, University of Arizona and Northern Arizona University—would appoint the “volunteers” who would compose the grade challenge department. These volunteers would conduct student hearings, and the bill says the board would have to provide “staff to support the department as necessary.”

But the board opposes the legislation. “We believe that the bill circumvents and undermines a current existing process, an appeals process that works well,” Thomas Adkins, the board’s vice president for government affairs and community relations, said in testimony to the House education committee.

“We do think the existing system works as is,” Adkins said. But he said he was open to changes to the current process, and to hearing student input on it.

In an email, a board spokeswoman wrote that “all three universities have robust grade appeal policies and allow students to begin the grade appeals process with an informal conversation between student and instructor. It then can escalate through a few steps before culminating in a larger academic committee review.”

In a statement, the University of Arizona said it “opposes this bill and is lobbying against [it] along with the other two state universities and Arizona Board of Regents. All three universities have an internal process which we believe is the best and most efficient way to deal with grade challenges.” Spokeswomen for Arizona State and Northern Arizona universities wrote in emails to Inside Higher Ed that they don’t comment on pending legislation.

Kern, in his brief remarks on the Senate floor, said he was aware of the board’s opposition but discounted it. He said “I still have yet to be convinced” that the board is necessary. He added that he’s trying to make the agency “accountable for the six-digit figures that they all get.”

Despite this, his bill would give that board the power to staff the grade-challenge department, to appoint the volunteers who hear the challenges and to directly hear appeals itself from students who lose before the grade-challenge department.

Criley questioned the idea of the board appointing volunteers to gauge whether grades are politically biased. “It’s the faculty who are engaged in the daily work of grading assignments and courses who are best equipped to review their peers’ work to determine whether grades were fairly assigned,” he said. “There’s an irony here, too, in that political appointees, the Board of Regents, [would be] selecting a review board to assess questions concerning political bias.”

“The AAUP has long held that the assessment of student work and the assignment of grades is a fundamental academic freedom right by faculty members,” Criley said. “But we also recognize that students have to have the opportunity to challenge or contest a grade.”

The AAUP has posted a recommended policy in which the “department head” or “the instructor’s immediate administrative superior” can change a student’s grade. But that’s only after the professor is given a say before a committee composed of faculty members in the instructor’s department or closely allied fields, and the committee still recommends changing the grade.

Leila Hudson, the elected chair of the faculty for the University of Arizona, called the bill “extremely heavy handed.” But Hudson—who’s in a public spat with the Board of Regents, including being threatened with a lawsuit by the then-chair after accusing him of a conflict of interest—had some criticism for the Board of Regents and the universities themselves. The University of Arizona discovered it had a financial crisis in November and faces a projected $177 million shortfall.

The bill is “a highly politicize-able solution to a nonproblem and most professors obviously wouldn’t dignify this with a response,” she said. “But, but, let me say, more importantly, it’s a sign that people understand that there are management issues in our public universities—another sign of the critical crisis of management and maladministration in our universities.”

Hudson said her preferred solution is recognizing “the importance of the faculty and the other stakeholders in the regulation of the university.” She mentioned students, staff and community members as being among those other stakeholders, but said faculty members “are by far the most important check and balance on academic programs and performance. We value the input of those other stakeholders, but the robust traditions of faculty and academic freedom are the best guarantors to prevent political abuse.”

“Anything that concentrates power in the unaccountable hands of the Board of Regents and their delegates is a step in the wrong direction,” she said.