You have /5 articles left.

Sign up for a free account or log in.

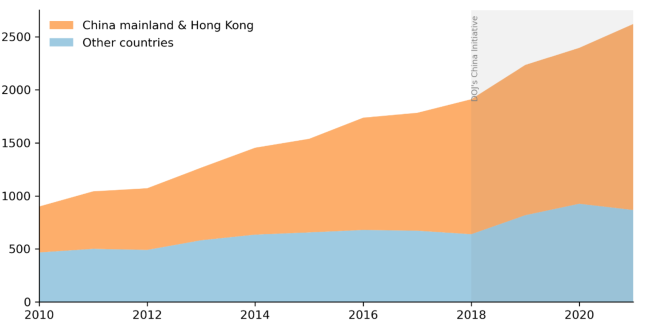

The annual number of Chinese-descended scientists who have left the U.S. for either China/Hong Kong or other countries.

Supplementary materials for “Caught in the crossfire: Fears of Chinese-American scientists”

When the Department of Justice announced its China Initiative in 2018, it said protecting national security was a goal.

But a new study in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences suggests the initiative’s investigations may have caused valuable researchers of Chinese descent to leave the U.S. for China.

The paper, “Caught in the crossfire: Fears of Chinese-American scientists,” doesn’t confirm causation between the initiative and the departures. Its data, from 2010 to 2021, shows that the annual number of Chinese-descent scientists leaving the U.S. was steadily increasing before 2018.

But the trend greatly accelerated that year, the study found.

“The migration has increased during those 12 years, from 900 scientists in 2010 to 2,621 in 2021, with an accelerated departure rate (75 percent higher) in the last three years … coinciding with the launch of the China Initiative in 2018,” the authors wrote.

The Justice Department, which didn’t comment for this story, ended the initiative in early 2022. The authors wrote that there are questions over how much “the formal dropping of the ‘China Initiative’ name has been accompanied by substantive changes in the government’s practices that address the chilling effects.”

News on the investigations is still emerging—in April, a judge ordered a former Harvard University department chair to pay over $80,000.

There were other convictions, but many of those charged were never tried or convicted.

“So far, the China Initiative has openly investigated about 150 academic scientists and prosecuted two dozen of them with criminal charges … with many more investigated in secret,” says the paper, from researchers at Princeton University’s Paul and Marcia Wythes Center on Contemporary China, Harvard, and the Massachusetts Institute of Technology.

The study also reports results from a December 2021 to March 2022 survey of about 1,300 Chinese-descended tenured and tenure-track American scientists.

The survey’s sample wasn’t probability based, and it may not represent the full population, but the results showed “general feelings of fear and anxiety that lead them to consider leaving the United States and/or stop applying for federal grants,” the authors wrote.

“If the situation is not corrected, American science will likely suffer the loss of scientific talent to China and other countries,” the authors wrote.

“Relative to the size of the total Chinese-American scientist/engineer population, the number who have returned to China is very small,” they wrote. “The vast majority prefer to stay and continue their work in the United States. However, they now fear that their work and lives in the United States may be jeopardized by the China Initiative.”

“I don’t feel safe anymore. I don’t apply for federal grants,” said Kai Li, a Princeton University professor and Asian American Scholar Forum founding vice president who wasn’t a report author.

“Why do we lose talents?” Li asked. “That’s a combination of issues, but mostly due to a chilling effect—and the chilling effect in the name of national security. But if we’re losing talents, that’s a national security problem by itself. If we don’t have the top talents, we’re losing leadership in science and technology.”

Li noted that the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development released a report this year noting a similar trend of researchers returning to China.

“Data on net flows of scientific authors show recent declines in the United States, becoming a net outflow in 2021,” says the OECD’s “2023 Science, Technology and Innovation Outlook.” “Net inflows of scientific authors into China mirror these declines to some extent, which points to Chinese scientists returning from the United States. The European Union’s growing attractiveness for scientific authors is partly a result of Brexit, with EU scientists returning from the United Kingdom.”

The OECD noted how much the U.S. relies on Chinese immigrants for its research and development.

“Foreign-born workers comprised 19 percent of the science, technology, engineering and mathematics (STEM) workforce in 2019, up from 17 percent in 2010,” the OECD report said. Forty-five percent of “workers in science and engineering occupations at the doctorate level were foreign-born, with the highest shares among computer and mathematical scientists. Around half of foreign-born workers in the United States whose highest degree was in a science and engineering field are from Asia, with India (22 percent) and China (11 percent) as the leading birthplaces.”

The OECD report also showed that, in 2020, China finally surpassed the U.S. in its output of top-cited scientific publications. China had been gaining in this area since at least 2007, while the U.S. has declined in recent years.

Citing this OECD report, David J. Bier, associate director of immigration studies for the libertarian Cato Institute, also pointed to the China Initiative.

“This is a disturbing trend that started before the pandemic,” Bier wrote in April. “In fact, it appears to coincide with the Trump administration’s ‘China Initiative’—more accurately titled the anti‐Chinese initiative. Launched in November 2018, the Department of Justice’s campaign was supposed to combat the overblown threat of intellectual property theft and espionage. In reality, it involved repeatedly intimidating institutions that employed scientists of Chinese heritage and attempting malicious failed prosecutions of scientists who worked with institutions in China.”

Bier wrote, “Although the Justice Department claims to have shut down its ‘China Initiative,’ my colleagues doubt that Chinese scientists will be free from unjust scrutiny going forward.”

The new Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences study said it estimated migration trends using surnames: researchers “collected 832 common Chinese surnames from Wikipedia” and searched for scientists with those names in “the large-scale academic bibliometrics database Microsoft Academic Graph.”

“This methodology results in the non-counting of Chinese scientists who have changed their surnames (usually females after marriage), leading to an undercount,” they wrote.

Over all, they found about 1.6 million “Chinese scientists” who “had their first publications in U.S. affiliations.” They then identified, out of those, over 12,000 who began their careers in the U.S. but left for China (including Hong Kong, but not Taiwan) from 2010 to 2021.

Gisela Perez Kusakawa, the Asian American Scholar Forum’s executive director, noted the fears shown in the study’s survey results.

“We are going to have a younger generation who don’t feel that they’re welcomed in the United States,” Kusakawa said. “Despite the fact that many of them want to contribute to U.S. leadership.”