You have /5 articles left.

Sign up for a free account or log in.

College leaders are grappling with how to respond to war between Israel and Hamas.

Illustration by Justin Morrison/Inside Higher Ed

Reverberations from the war between Israel and Hamas are shaking U.S. higher education as the conflict spills out onto campuses across the nation, pitting protesting students against one another and forcing college presidents to take a stand on a conflict thousands of miles away.

Presidential responses have elicited criticism from supporters on both sides. Students and faculty members have blasted college and university leaders for not releasing statements at all, for speaking up too late or for speaking too forcefully—or not forcefully enough.

That makes it virtually impossible for college presidents to navigate the issue without alienating student groups, angering donors and trustees, or prompting backlash from multiple quarters.

What presidents do or don’t say, or even when they say it, has the potential to cost universities millions of dollars in likely donations. At Harvard University and the University of Pennsylvania, among others, donors have publicly denounced the way leaders are handling their campus’s response to the Hamas terrorist attacks and the war in Gaza. Input from ex-presidents and politicians has also added to the pressure.

At both institutions, a key concern was that presidents didn’t speak up soon or forcefully enough.

Pitfalls of Political Statements

In Harvard’s case, the backlash centered less on the administration’s initial statement than on President Claudine Gay’s failure to denounce numerous student groups who signed on to a controversial open letter stating that Israel was “entirely responsible for all unfolding violence.”

Former Harvard president Lawrence Summers and U.S. senator Ted Cruz of Texas seized upon Gay’s hesitancy to address the letter, with Summers accusing Harvard of appearing “at best neutral towards acts of terror against the Jewish state of Israel.” Cruz initially called Harvard’s silence on the student letter “indefensible”; later he wrote on X that he was “ashamed that student groups from my alma mater, Harvard, blamed Israel for Hamas’ genocidal terrorist attacks.”

Since then, multiple donors have reportedly broken ranks with the institution.

Penn’s initial statement, which critics saw as inadequate, prompted trustee Vahan H. Gureghian to resign and certain donors to pull their support; former politician Jon Huntsman reportedly said in an email to President Liz Magill that “silence is antisemitism” and that the Huntsman Foundation “will close its checkbook on all future giving to Penn.”

Even as wealthy donors and trustees criticized the president for her alleged lack of support for Israel, multiple students and faculty members walked out of classes on Monday, calling for Penn to do more to support its Palestinian students. Participants in the walkout told local media that Magill had not addressed the loss of Palestinian lives in her recent statement.

Even fairly mild statements have sparked outrage.

At Pitzer College, President Strom C. Thacker issued a brief statement expressing his “deepest concerns and condolences for the many hundreds of lives of Israelis, Palestinians, and others lost and thousands injured over the past few days in Israel and Gaza.” He added that while Pitzer is far removed from the conflict, it has affected community members “who have had loved ones perish, threatened, or injured in this horrific violence, and for all of us who mourn such profound losses.”

Thacker’s statement was then pilloried on Fox News, where a parent of a current student described the president’s remarks as “offensive and morally repugnant.”

At Cornell University, President Martha Pollack has issued multiple public statements about the conflict. When an initial message on Oct. 10 apparently did not go far enough for some critics in condemning the attacks, Pollack issued another statement the same day, declaring “that the atrocities committed by Hamas this past weekend were acts of terrorism, which I condemn in the strongest possible terms.”

Pollack has since issued two more statements, one on Monday and another on Tuesday, disavowing comments made by Cornell professor Russell Rickford, who called the attacks on Israel by Hamas “exhilarating” and “energizing” at a pro-Palestine rally in Ithaca Sunday.

At Rutgers University, President Jonathan Holloway released two statements. In the first he said, “Watching the news of the horrific attacks and tragic loss of life in Israel and Gaza has been heart-wrenching” and encouraged the community to “operate from a place of compassion and empathy.”

In the second statement, Holloway wrote, “What Hamas did in brutally murdering, torturing, and holding hostage innocent Israeli victims of all ages was unconscionable and an act of terrorism.” He also addressed the “suffering pain, anguish, and fear” of the Jewish community at Rutgers” and expressed “concern for members of the university community with family and friends in Gaza.”

His remarks prompted an open letter from nearly 200 professors who accused Holloway of a one-sided approach that ignores the pain of Rutgers students with family and friends in Gaza.

“Like you, we mourn the loss of all human lives and we welcome efforts to invite empathy and denounce violence against all civilians,” Rutgers faculty members wrote in the open letter to Holloway. “However, your deeply one-sided message was a gut punch to the many Rutgers students who have family and friends in Gaza and Palestine. It also failed to acknowledge the ongoing hate and racism directed at our Palestinian, Arab, and Muslim students, who have never known a world where they are not vilified as terrorists for simply being brown, Muslim, or Arab.”

Other presidents have focused their statements on the acts of terror perpetrated by Hamas and either ignored or touched lightly on the decades of political tensions between Israel and Palestine and the allegations that the Israeli government has long maintained an apartheid system.

University of Florida president Ben Sasse has been sharply critical of college leaders for equivocating statements that he believes have failed to adequately condemn attacks on Israel as terrorism. Sasse, a former Republican U.S. senator, told Fox News in an interview that while leaders address “Halloween costumes and micro-aggressions,” they have failed to condemn “the most grave, grotesque attacks on Jewish people since the Holocaust” while they claim “there’s too much complexity to say anything."

Sasse also wrote a letter to Jewish alumni forcefully condemning the attacks, declaring that “what Hamas did is evil and there is no defense for terrorism.” But despite Sasse’s criticism of other college leaders for not speaking up, the University of Florida has apparently not yet issued an institutional statement beyond Sasse’s remarks. (A UF spokesperson did not respond to a request for comment.)

To Speak Up or Not?

Some institutional leaders and high-ranking officials have addressed the pitfalls of speaking up.

At Williams College, President Maud Mandel noted in a message to campus that she had heard concerns about her lack of a statement “following the recent, horrific attacks by Hamas on Israelis and the deaths of Palestinian civilians in the military retaliation.” Mandel explained that it is her policy not to “send out campus-wide messages about domestic or international events or even natural disasters, no matter how tragic or painful.” The reason, she explained, is that such issues occur too frequently and because she prefers to focus on the college’s core mission.

“This position represents an evolution in my thinking. Earlier in my presidency I sent out public statements about various world events. After conversations with members of our community and colleagues at other schools, I have become convinced that such communications do more harm than good,” Mandel wrote last week. “They support some members of our community in particular moments while intentionally or unintentionally leaving out others. They give some issues great visibility while leaving others unseen. As president of Williams I want to focus my energy on caring for students in the moments that are important to you, by working with our incredible faculty and staff who to provide learning opportunities, support and mentorship.”

Mandel also used the statement to announce a campus vigil for the lives lost in the conflict.

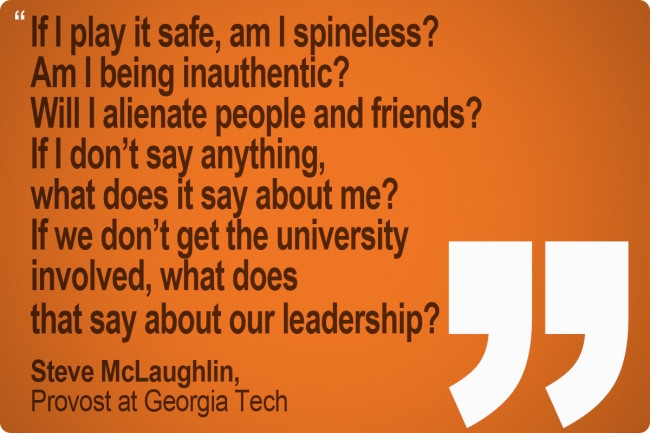

Georgia Institute of Technology provost Steve McLaughlin took to LinkedIn to discuss the challenge of issuing statements on troubling world events in his leadership capacity.

“It’s all impossible,” McLaughlin wrote in a LinkedIn post. “If I play it safe, am I spineless? Am I being inauthentic? Will I alienate people and friends? If I don’t say anything, what does it say about me? If we don’t get the university involved, what does that say about our leadership?”

McLaughlin’s post has since promoted more than 130 responses. Some commenters argued that universities should steer clear of politics, while others suggested that colleges have an institutional responsibility to speak up on matters that run afoul of institutional values.

“Apartheid in South Africa wouldn’t have ended but for institutional courage and conviction. Overt racism, sexism and homophobia have historically been called out and challenged by leadership in higher education,” Larry Moneta, a former Duke University administrator, wrote in reply. “Current timidity by institutions and by their presidents showcases diminished courage and fear of being challenged. Yes, you’re being spineless … but, sadly, you’re in good company.”

Presidents as Moral Leaders

Marjorie Hass, president of the Council of Independent Colleges, told Inside Higher Ed that college presidents are viewed as public intellectuals and increasingly as moral leaders expected to make statements on major and controversial world events that affect various constituents.

And such statements can backfire given the diverse nature of college campuses.

“Everything is a pitfall. You cannot come up with any kind of statement that will not make some people feel angry or upset. I certainly never managed to do that,” said Hass, the former president of Austin College and Rhodes College.

In recent years, pressures have mounted on college leaders to speak up on controversial issues. Hass pointed to the 2016 election of Donald Trump and the 2020 murder of George Floyd as flash points. And, in the internet era, many constituents expect almost immediate commentary from leaders.

Hass said she believes she would struggle in this moment to communicate her thoughts to a campus community, given that she is Jewish and would need time to process her own feelings following the initial attacks in Israel.

Plus, community expectations for a president can be impossible to meet, Hass said.

“I do think presidents have responsibility to be responsive to the climate and tenor and emotions on their campus,” she said. “And I do think they have a responsibility to affirm and assert their institution’s mission in relationship to broader issues. But I don’t think that presidents should be looked to to provide a definitive institutional stance towards very complicated geopolitical issues.”