You have /5 articles left.

Sign up for a free account or log in.

The University of Arizona will change its budget processes following major financial miscalculations, which have also led to more oversight from the Arizona Board of Regents.

Photo illustration by Justin Morrison/Inside Higher Ed | Documents: Arizona Board of Regents | Photo: Getty Images

The University of Arizona announced dramatic changes to its financial oversight Wednesday in the wake of last month’s embarrassing revelation that administrators had miscalculated the institution’s cash on hand by hundreds of millions of dollars.

First and foremost, President Robert Robbins accepted the resignation of CFO and senior vice president for business affairs Lisa Rulney, on whose watch the multimillion-dollar blunder took place.

While the Arizona Board of Regents requires public universities to have 140 days’ worth of cash available, University of Arizona officials announced Nov. 2 that that cushion had fallen to 97 days for fiscal year 2024. The news came after administrators told the board in June that the university had 156 days of cash on hand—a $240 million mistake caused by accounting errors and flawed financial projections. (This paragraph has been updated to correct the number of days institutions are required to have cash on hand; it's 140, not 120.)

At a special meeting Wednesday, the Board of Regents outlined the steps it would take to try to restore UA’s financial health. Those measures include implementing a hiring and compensation freeze and eliminating tuition guarantees for new students beginning in fall 2025, though current students will not be affected.

Improving Financial Oversight

During the meeting, Regent Fred DuVal said that UA’s sudden reduction in days of cash on hand last month was “unseen and dramatic,” but he noted that it was a symptom of two larger problems: an ongoing budget deficit and an inadequate finance and reporting structure that failed to identify the problem sooner.

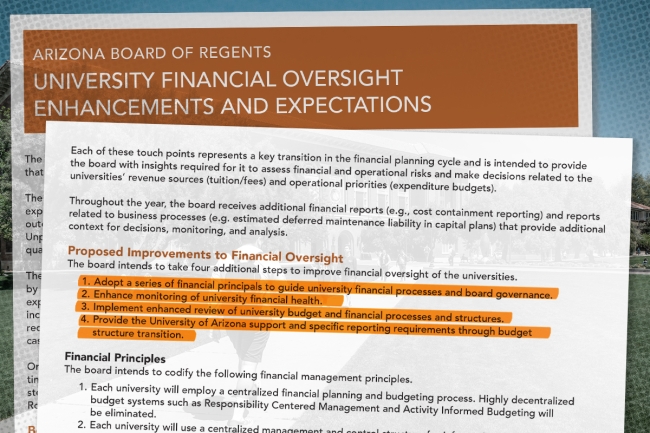

To that end, the regents approved plans to adopt additional financial management and reporting oversight, implement monthly budget reviews, increase transparency, ensure greater accountability, and centralize administrative services in IT, human resources, communications and marketing, and advancement, among other things.

To address the budget deficit, the university will freeze international employee travel, restrict purchasing, defer nonessential capital projects and conclude strategic initiatives funding.

DuVal said the regents would not touch financial aid for Arizona residents, institute “systemic” furloughs or reduce retirement or benefits commitments for employees.

Robbins acknowledged the particular challenge that high-priced sports pose to addressing the deficit.

“Athletics is the most difficult part of the university’s budget,“ he said during the meeting. “I also believe that athletics is a core part of the University of Arizona and a key element to our long-term success.”

He said the university was committed to upholding a multiyear plan to bring the athletics budget into balance, in part by raising ticket prices for events and expanding media rights. In the past, Robbins has warned that cuts in athletic could be especially “draconian,” due to steep financial losses prompted by a $55 million loan during the COVID-19 pandemic, which he acknowledged has not been paid back fast enough.

Job Cuts and a Hiring Freeze

Faculty members have been seeking clarity since the revelation of financial missteps, which many blame on the failure of university administrators to adequately monitor UA’s cash balance. The possibility of sweeping job cuts has loomed large.

Robbins did not spell out any specific job cuts at the Board of Regents meeting, though the plan referenced coming efforts to “eliminate redundancy and create operational and financial efficiencies” across UA’s workforce.

But the president has offered some insights at recent faculty meetings. In response to questions at a Dec. 4 Faculty Senate meeting, Robbins said, “It’s going to be [up] to each of the unit managers to decide about how to manage their budget.” Robbins also noted that the administrative ranks at the University of Arizona have expanded significantly—growing by 69 percent over the last 10 years—and will be subject to cuts.

“We will have to make some difficult choices,” he said at the meeting.

Who Bears Responsibility?

Rulney’s resignation, announced at Wednesday's meeting, came roughly a week after a faculty member asked her if she intended to step down. While presidents and chief financial officers often resign when deemed responsible for major financial missteps or scandals, it took more than a month for an administrative shake-up at UA.

Ted Downing, a research professor of social development who has been on the UA faculty since 1971, asked Rulney directly at the Dec. 4 meeting if she would resign.

“Lisa, with this happening, why did you not at least tender your resignation and offer to resign? Any other CFO of any other major organization this large would have done that,” he asked.

While Rulney acknowledged her “responsibility for overestimating our days-cash-on-hand ratio,” she said she intended to focus on solving the problem unless Robbins asked her to step down.

“I want to help work through this challenge. We have been through bigger changes before; we’ve been through a global pandemic, and we got through it because we all worked together,” Rulney responded.

But by Wednesday she had stepped down. Robbins announced that John Arnold, the Board of Regents’ executive director, will serve as interim CFO.

Two days earlier, in a special meeting on Dec. 11, the Faculty Senate voted to request an external audit of the university’s finances. Chair Leila Hudson noted that the vote was “largely symbolic,” given that the body has no authority to force any type of audit at UA, let alone one in addition to the internal audit already conducted by the university.

The Faculty Senate has also discussed holding a no-confidence vote in Robbins. If passed, it would be the second one since March, when the body condemned the university’s handling of the murder of a professor on campus.