You have /5 articles left.

Sign up for a free account or log in.

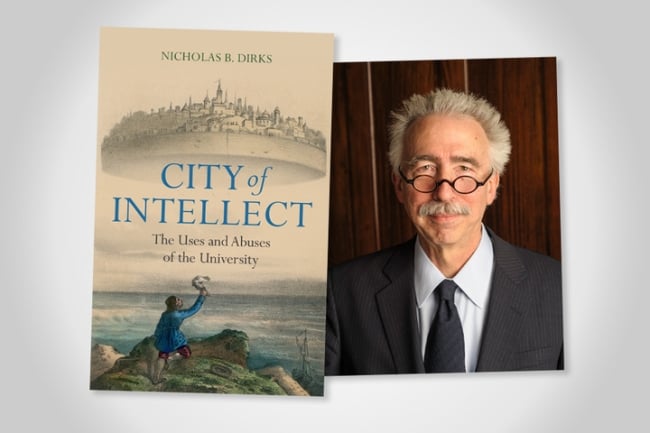

Photo illustration by Justin Morrison/Inside Higher Ed | University of California, Berkeley

In his new book, City of Intellect: The Uses and Abuses of the University (Cambridge University Press), Nicholas B. Dirks candidly reflects on his short and challenging tenure (2013–2017) as chancellor of the University of California, Berkeley. His experiences there—and during his prior stint as executive vice president and dean of the faculty of arts and sciences at Columbia University—portended many of the tensions currently roiling college campuses and helped shape his views on the current state of higher education. A blend of memoir and analysis, City of Intellect explores the dizzying array of issues college leaders face, from budget cuts and combative boards to faculty feuds and controversial speakers on campus.

Dirks, an anthropologist and historian who currently serves as president and CEO of the New York Academy of Sciences, spoke with Inside Higher Ed via Zoom. Excerpts of the conversation follow, edited for space and clarity.

Q: The average college presidency keeps getting shorter. In the last American Council on Education survey, I think it was under six years. Your term as chancellor was even shorter—four years and change. How would you characterize it?

A: Well, it was a roller-coaster ride, really, from start to finish. And it felt at the time like a lot longer than four years. I intended to do it for much longer. But my Berkeley experience began when I thought the state of California was coming out of the recession. I assumed that the kind of funding cuts that had been so draconian, in the wake of the Great Recession, were going to be reversed. When I arrived, [then governor] Jerry Brown—who was very friendly when I first came, but nevertheless critical of everything from my compensation to my failure to come up with a quick way to bend the cost curve of higher education—announced almost immediately that there would be a tuition freeze and that he would not, in fact, restore the funding cuts that had taken place three or four years before. So I arrived thinking that things were going to actually be much better, and in the space of just a year and a half, the university was running a structural deficit of $150 million. And that just took my breath away.

The kind of cloud over my entire time at Berkeley was a sense that not only were we working with a governor who actually wanted to force us into a kind of austerity, but that I was doing so without many of the levers that I was accustomed to in a private institution, where you could move things around—for example, increase your proportion of out-of-state or international students, increase tuition up to a point, and so forth.

Q: Given all the forces outside a college president’s control—in addition to state budgets, you’ve got demographic shifts, global events, the whims of students and faculty, and so on—it’s impossible to please everyone. So how do you decide what to prioritize knowing that you’re going to make some people unhappy?

A: When I first arrived, I did the usual kinds of listening rounds to try to understand what people’s concerns were, what major issues I could take on. And I decided fairly early on that I was going to try to address the state of undergraduate education, which I’d been very focused on at Columbia. I was going to look at the global footprint of UC Berkeley—another thing that I brought with me not only from my administrative experience, but also as an academic who had worked in India. And I was going to try to promote interdisciplinary collaboration within the university, as well as greater institutional partnership opportunities outside Berkeley.

I started on the first of June, but by the time I gave my inaugural address in November, there had already been a couple of crises that immediately started moving aside all my best-laid intentions and plans. One was that there was great unhappiness about the response of the university to Title IX violations around sexual abuse among students, and failure on the part of the office to get back in a timely way to resolve cases. And the second crisis was around the academic performance of the football team in particular, and men’s basketball, because the graduation rates had gone down below 50 percent for those two revenue sports. So questions around the academic integrity of intercollegiate athletics became a kind of crisis. And I had to convene a task force on both of those even before I gave my inaugural address.

Q: You had this sort of parallel experience at a public institution and a private institution, Berkeley and Columbia, both highly politicized campuses. Aside from the funding issue, what were the other major differences between the two?

A: I actually assumed somehow that Columbia’s high level of politicization had well equipped me to go to Berkeley. I even quipped in the interview, when I was asked how I dealt with student protests, that I’ve been at Columbia, which was “Berkeley on the Hudson,” and got a laugh or two out of that.

But I found that as a university president, probably the biggest difference between a private and a public was that at Columbia, the president was hired by a Board of Trustees who worked very, very closely with the president and who felt a certain level of responsibility for having made the appointment. It’s not that boards don’t turn against their appointees, but they begin with the presumption that they want to work together. And they work in a way that is less open to public scrutiny because there aren’t public meeting requirements for private boards.

When you go to a place like the University of California, not only do you not have a Board of Trustees, but the Board of Regents is responsible for the entire system—10 campuses and four major national laboratories. And, of course, like other boards of regents, they are political appointments in California; they’re literally appointed by the governor, and they are people who don’t necessarily have a direct relationship with any one university. When I moved to California in 2012, there was only one Berkeley alum on the entire board, aside from Jerry Brown, who was ex officio. But he was dedicated to the idea that Berkeley [should] cut its budget dramatically. I should have known this, of course, but the Berkeley role was incredibly political. And I had to sort of watch my own back since I didn’t have a board that was assisting in that feature of the job.

Q: Political interference is becoming increasingly common in higher ed, particularly in red states where Republican governors are trying to exert their influence on colleges, whether through appointing like-minded leaders, dictating curricula or banning DEI initiatives. What does that say about the future of public higher education?

A: I feel like I had a foretaste of the extreme political meddling that has just gotten worse and worse and is especially pronounced in places now like Florida and, to a lesser but still important extent, Virginia and Texas. And it deeply alarms me. I think it’s a very, very troubling trend for public higher education … Universities have often invited political scrutiny by virtue of not being entirely consistent in the way in which they deal with certain kinds of issues. But almost always, the political intervention is far worse than the political problem on campus.

Q: You had firsthand experience of the free speech wars at Berkeley, including when the College Republicans invited right-wing provocateur Milo Yiannopoulos to campus and violent antifa protesters forced you to cancel the event. What should universities do in those situations, when you have free speech pitted against student safety?

A: The question, of course, is always what kind of safety are we talking about? And, as I think back to that event, the sad truth is that there were both issues around safety that have to do with speech and speech alone, as well as issues having to do with safety, which involve the possibility of physical harm. And when that happens, it’s a very different kind of issue.

The charge that speech I don’t like or that I find offensive is going to cause irreparable harm and trauma is one that universities have tried to deal with, but public universities really have no choice but to adopt the full provisions of the First Amendment—namely that we will do nothing to prevent whatever political statement or view as long as it accords with the provisions of time, place and manner. Which is to say it takes place in a public square kind of event on campus and that it follows certain kinds of protocols around registering events—not around the content of the political speech. In a public university, it’s easier than in a private because you don’t have a choice.

The lawyers all told us the same thing: you cannot disinvite a speaker on the grounds that somebody says they’re going to find what they say traumatic. Of course, in that case there was the possibility of a violent protest—there was a violent protest. Nobody, thank God, was hurt, but $100,000 worth of damage was done on campus. And it was genuinely touch and go as to whether or not there would be, in fact, some kind of physical harm.

Q: After the event was shut down, Donald Trump, who was president at the time, tweeted that Berkeley should be defunded. So even though there were literally fires burning on campus, you were derided as an enemy of free speech.

A: The truth is that kind of attention did have real effects—not just in terms of threatening the withholding of federal funding, but also because many people asked, both directly as well as on social media, why the police didn’t do more to control antifa? What was wrong with us that we hadn’t fully anticipated the problem? And as you may know, two months later, Ann Coulter announced that she was coming to campus at the same time that the Proud Boys announced they were going to come and make sure that Coulter would be allowed to speak on campus. And we did, in fact, think, “OK, well, we thought we had made adequate preparations for Milo’s visit; now we really have to think about doing something much more than that.”

Between me and a couple of events that happened after I stepped down and Carol Christ took over, in the course of the next six months, the university spent millions of dollars on police protection—which, given our finances, was not money we had. When there were barriers set up all over campus making it look like it was either a crime scene or a war zone, students genuinely began to express concerns and justifiably said, “I came to the university to study, not to be part of a set of riots.”

Q: So what can universities do to guarantee both free speech and the safety of students?

A: First, I do believe that universities have to be able to protect freedom of speech across the board for various reasons. One is that it is consistent with the values of open inquiry and academic freedom that I think universities have to work very hard to safeguard under the kinds of circumstances in which we live.

The other part is that if you say, “I’m not going to allow Bill Maher or Milo Yiannopoulos or Ann Coulter to come,” next year, somebody’s going to say, “Well, you can’t have Noam Chomsky” or somebody who is on the left. And of course, at Berkeley, it’s gone around the circle several times; Reagan began his political career by complaining about visits by Stokely Carmichael and even Robert Kennedy back in the early ’60s. So, you know, what goes around comes around.

Now we’re in this world in which some speakers occasion not only threats but the reality of violence occasioning the need to seem to militarize the campus, which is a horrible thing to do. And yet, you do have to work very hard to literally protect the safe space of the university, which is to say, keep students and faculty and staff out of harm’s way. And that that can be a logistically difficult and expensive thing to do.

The problem, in part, is that there are groups that are actually seeking to encourage controversial speakers to come to campus to shine a light on the inconsistency of universities around different political points of view. And at that level, you know, the plea for viewpoint diversity is one that, clearly, universities have to think very hard about.

Q: Is it the university’s role to take a political stand?

A: The university is a place where different kinds of political stances can be expressed, but it should not take a political stance, per se. That’s easier said than done. A lot of the focus these days on the Kalven report from Chicago that goes back to ’67 forgets that it’s actually very difficult to make a distinction between a statement about certain kinds of values and a statement about politics. University administrators are always talking about creating a respectful environment for intellectual exchange, but that’s a value, and it can easily then map itself onto a political position.

But I also don’t think that universities should have foreign policies or be called upon to comment on every political event that takes place. And yet, you know, the obvious concern about presidential responses to Oct. 7 was predicated in large part on the fact that there were immediate and quite clear responses on the part of university presidents to the murder of George Floyd, to the Russian invasion of Ukraine, to any number of other external political events, and those are things that set the stage for the current concern about consistency.

Q: Reading your account of being at Columbia and dealing with the David Project and Campus Watch in the mid-2000s reminded me that the current campus tensions over Israel and Hamas are not exactly new; they’ve been going on a long time. But do you think they’ve gotten worse? And how should administrators deal with the intensity of feeling and reaction on their campuses?

A: It’s very easy to be on the sidelines and say what they should do, and I just want to be respectful to the people who are sitting in these incredibly difficult jobs. The one thing that I certainly know from my own experience is that the pressures are intense. On the one hand, university administrators have to explain to members of boards, donors, alumni, what it really means to be respectful of academic freedom. And that often means having hard conversations about the nature of offense, and so on. And in the last 20 years—it was 20 years ago this year that I became a dean at Columbia and dealt with the Middle East politics that I describe in the book—a lot has changed, and it has become more difficult to make the case for academic freedom, given the amount of attention that is given to creating safe spaces on university campuses.

But I also think there’s been a shift in terms of the demographics of political support for things like Palestinian statehood—a kind of generational shift. Ultimately, I guess the real conundrum is that we need to find perhaps new ways to allow protests to take place that do not constantly seem to bleed into acts of violence. There’s too fine a line between a protest and an action that is seen by students as constituting the basis on which they claim worries about their own physical safety.

Q: But how do you do that?

A: I mean, I was asked repeatedly, for example, to ban Students for Justice in Palestine, and I didn’t; I didn’t think banning legitimate student organizations was a good thing to do. But I do think that rigorous attention to questions around time, place and manner need to be thought through again to ensure that protests can be seen and heard, without the disruptive effects. I say that as somebody who was routinely accosted in my house, in my office, even in the local supermarket, and began to feel increasingly—and I felt this for my family … You can’t just say that it’s paranoia to feel physically endangered when there’s a mob around shouting slogans at you very loudly in aggressive kinds of ways.

Q: So are you really glad to not be a president right now?

A: [Laughter] Yes and no. I feel like I did learn a thing or two in the days I spent in those offices. Even the scraps I had with people like Jerry Brown could have at least helped me if I were in that terrible situation in Washington having to address questions from a hostile congressional inquiry. But I do sleep better.

Q: Throughout your career, you’ve been very interested in interdisciplinary work and melding arts and sciences. Where does higher ed stand on that right now and how will it inform the future of the university?

A: I got involved in administration by creating a joint Ph.D. program at Michigan, so yes, it’s always been my kind of passion. There’s a lot of talk about interdisciplinarity. But I do worry sometime that in major research universities, the disciplines have become part of the problem and not part of the solution to really addressing some of the current crises in higher education—for example, trying to figure out what the liberal arts might mean in the mid-21st century. Too often, at places like Columbia and Berkeley, faculty who were hired and evaluated and promoted within departmental or disciplinary frameworks don’t take on some of the larger questions that would take them out of their comfort zones, perhaps, but also out of their departmental lives and help them rethink how you would deal with, say, decline of interest in English majors or some of the questions around the humanities and artificial intelligence. It too rarely gets built into a curricular revision of undergraduate teaching, because, of course, faculty live within their departments.

Q: What’s your best piece of advice for people now sitting in the president’s chair?

A: Well, I don’t know if this is good advice or just something that I feel needs to be done. But I certainly think that given the growing distrust of the university, the attacks and assaults that are taking place … suggests we need a far more robust defense of the university. The defense is not simply about battening down the hatches and drawing in the wagons and acting as if the only problem is outside the university; we also need to really rethink some of the legitimate concerns people have about how we conduct ourselves at every level—cost, administrative bloat, disciplinary silos, relevance, enacting academic freedom and free speech—across the board. All of those things have to be done in order to regain trust.

But at the same time, a very robust campaign has to be made to talk about the importance of higher education. We see its relevance in our politics today, perhaps more saliently than ever before. And given the pace of change in our world, and also in the technical knowledge that is going to be part of any future for any young person today, the need for education has never been greater.