You have /5 articles left.

Sign up for a free account or log in.

Students and faculty members are calling on the National Science Foundation to re-evaluate its Graduate Research Fellowship Program after yet another student received an inappropriate comment on his application.

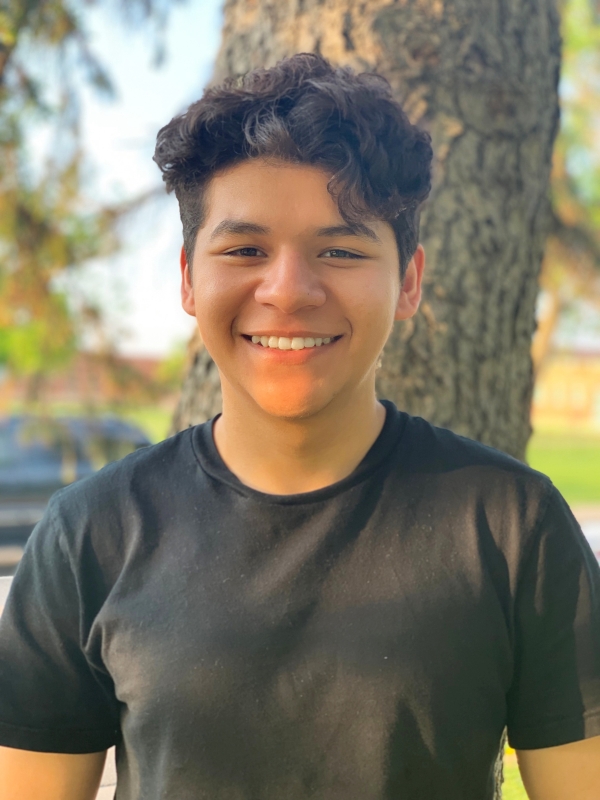

University of Minnesota

Ulises Perez, a senior at the University of Minnesota, Twin Cities, studying chemistry, was told by one reviewer that “his Hispanic pride prevented him from seeking mentorship and advise [sic] from other [sic] that would have helped him avoid and lesson [sic] some of his struggles and progress further.”

To Perez, the comment was strange. He said he didn’t talk much about his “Hispanic pride” in the application other than how he wanted to see more Latinos in science. His mentors have all been women and not people of color. He didn’t receive the fellowship.

To his faculty adviser and outside observers, the comment reflects systemic problems at the National Science Foundation and higher education overall and hinders efforts to encourage students from diverse backgrounds to become scientists.

The fellowship program—a premier grant for early-career scientists that comes with three years of funding totaling nearly $150,000—aims to support the next generation of STEM leaders and increase the participation of underrepresented groups in science and engineering. Yet it’s been criticized for a lack of demographic and institutional diversity among the students who receive funding.

“For most grad students, this is the ticket into any lab that they want and the freedom to work on any project,” said Renee Frontiera, an associate chemistry professor at the University of Minnesota and Perez’s adviser. “I think [the fellowship] really should be used to encourage people to go into science, and comments like this are so discouraging, not just for one person but for the whole community.”

Perez shared the comment on a Twitter account that he created just to post the screenshot, and the tweet quickly racked up hundreds of comments. Social media posts about inappropriate comments on fellowship applicants have become a seemingly regular occurrence in recent years.

“I don’t regret it,” he said, adding that he’s received a lot of positive support. “I think it’s been good to see other people share their experiences.”

I love the NSF GRFP!!! pic.twitter.com/2AjBpH3FId

— Ulises Perez (@UiisesPerez) April 17, 2023

Frontiera said she’s heard from other graduate students who received similar comments but were worried about speaking out publicly.

“I think the fraction you see on Twitter is a very small fraction of this,” she said. “Because there’s a big power dynamic between a big federal agency like the NSF and an undergraduate who has a lot ahead of them in terms of building a scientific career.”

Perez said he knew applying for the fellowship would be “a crapshoot.”

“Because I’ve seen the Twitter comments in previous years, I knew what to expect,” he said. “I knew my personal statement might come back to bite me in some way just because it’s not like there’s a solution to systematic racism in academia. I never expected it to be that specific.”

Perez and Frontiera did eventually file a formal complaint this week with NSF’s Office for Equity and Civil Rights seeking a formal apology and changes to the review process. The main issue, they said, isn’t the comment—which they both said was inexcusable—but that it wasn’t caught and was shared.

Frontiera, who has served on a review panel before, said that program managers with NSF scrutinize reviews and question even the use of gender pronouns.

“If you say certain things, they flag it and they do not let the comment get out,” Frontiera said. “How this made it through so many steps is just really bewildering. I’m not quite sure how many things had to go wrong to get it out.”

Others have raised similar concerns on social media following Perez’s post.

“NSF is aware that there are concerns in the community regarding the quality of reviews of the 2023 GRFP competition, and we take this matter seriously,” an NSF spokesperson said.

The NSF spokesperson said the agency has a mechanism in place to screen comments before they are released.

“However, due to the high volume of applications received, it is impossible for NSF staff to read every review for unintentionally biased comments,” the spokesperson said. “In rare cases, these comments are released to an applicant. Such comments do not impact NSF’s final decision on selecting an applicant, because all decisions are based on a holistic evaluation of the entire application package and all the reviews are provided by people who are experts in their fields.”

Fellowship applicants who feel they received an inappropriate review can submit comments to grfp@nsf.gov, the spokesperson said.

Rethinking the Fellowship

Cesar Estien, a doctoral student at the University of California, Berkeley, wasn’t surprised to see Perez’s post. He had seen other comments on social media and said many Black, Latina and queer scholars encounter similar rhetoric.

“Every year, this is brought up and every year people [tag] NSF on Twitter, and maybe they send emails, but nothing has changed yet,” he said.

Estien, who did receive a fellowship in 2021, said he was lucky with the reviewers he got. He and two other graduate students recently published a paper about how to improve the program—recommendations that included correcting reviewer bias. He’s not optimistic that NSF will take their recommendations, in part because the agency is intertwined with academia and STEM.

“There’s a lot of small, incremental change in academia,” he said. “The small, small steps that are just pushing off the larger stuff that does need to be changed, such as restructuring how we view fellowships or the qualifying exam. The things that actually serve as barriers.”

Juan B. Gutiérrez, a professor and chair of mathematics at the University of Texas at San Antonio, said that part of the problem is the review system itself and the manpower required.

Each year, NSF receives about 13,000 applications for the fellowship program, which are supposed to be reviewed holistically by three external reviewers who score the application and write comments.

Gutiérrez said the time commitment involved makes it difficult for more faculty members to participate and provide substantive comments for those who do. Reviewers do receive a flat fee and training about implicit biases.

He raised concerns with the NSF in 2020 after finding during one review panel that Hispanic applicants were more likely to not have completed reviews and declined to be a reviewer this year when those concerns weren’t addressed. Other reviews have criticized the review process as “dysfunctional” to Science.

“Most of the students who receive the fellowship are very good; I don’t think that there is a question about that,” he said. “The problem is when those who have merit were not properly considered or who received destructive feedback instead of constructive feedback. That is the issue.”

Frontiera said she would like to see NSF rethink the fellowship and how they review applications, given the stakes of the program and the challenges to find reviewers to comment on applications and serve on panels.

“I think awarding more of them for one year would be great,” she said. “I think that would have a much bigger impact and encourage a bunch of really fantastic students to go into science, whereas now it’s so competitive and this process is so negative that it’s actively discouraging really talented students. I think it’s harming more people than it helps.”

Perez said he’s not discouraged by the comment. It’s not his first time dealing with something like this, he said.

“I think my hardship has hardened me up in the sense of I’m willing to move forward readily, and I can use this experience to help out other people who are not used to this type of conflict or just the hardship in general,” he said. “I will move forward.”