You have /5 articles left.

Sign up for a free account or log in.

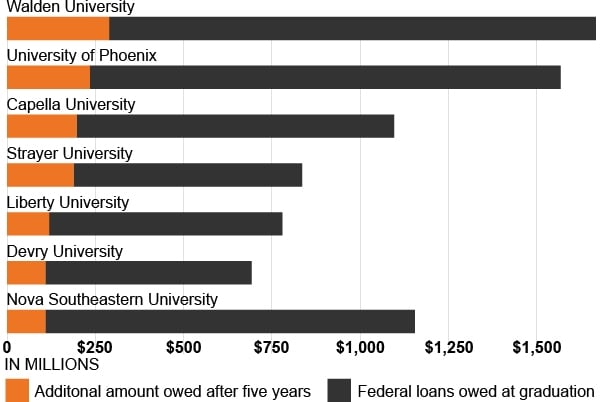

After five years, these seven institutions each accumulated more than $100 million in additional interest on loans taken out by graduate students.

The HEA Group and Student Defense

Some graduate programs leave students worse off financially, a new report analyzing students’ debt and earnings found.

The HEA Group, a research and consulting agency focused on college access and success, partnered with the National Student Legal Defense Network to analyze graduate student debt and whether programs across the United States allow students to repay their loans.

“With no checks and balances in place, this cycle where students take on massive amounts of debt—that they will never be able to fully pay back—will continue to occur,” says the report, released today.

At nearly one-third of the 1,661 institutions included in the analysis of Education Department data, students in a two-year cohort collectively owed more five years after entering repayment than they initially borrowed. At 24 institutions, a two-year cohort of students has accumulated more than $25 million in interest, according to the report.

The report also included debt-to-earnings ratios for more than 6,300 programs across the institutions. To download the underlying data sets, go to the report’s website.

Walden University, a Minnesota-based for-profit institution with more than 40,000 graduate students in fall 2021, topped the list of institutions where students owed more collectively than what they borrowed. Walden’s graduate students who borrowed in 2013–14 and 2014–15 owed $289 million more in loans five years after entering repayment, according to the report. The University of Phoenix ranked second; its graduate students’ balances had increased by $235 million. Among the top 24 institutions, 11 are private nonprofit, nine are for-profit and four are public. The report didn’t break down the debt owed on a per-student basis.

“It paints a picture of where students are five years after they leave graduate school at an institution of higher education,” said Michael Itzkowitz, founder of the HEA Group and the report’s author. “Some of it raises cause for concern as we can see students owing hundreds of millions of dollars more than the amount that they initially borrowed. This means that their pursuit of a better future may be delayed at best, and it may leave them worse off at most.”

Graduate students make up about a quarter of the country’s student loan borrowers and hold about half of the country’s total federal student loan volume. Policy makers and advocates have become increasingly concerned about the ballooning balances of these students and the outcomes of graduate school programs. The Education Department recently updated its public-facing College Scorecard to, for the first time, include program-level data about graduate schools, which Itzkowitz used in the analysis.

Chazz Robinson, a policy adviser for Third Way, a center-left think tank, said graduate programs and students have been forgotten about in federal policy discussions.

“A lot of this is due to the minimal data that’s provided on graduate education as a whole but with the department’s additions to the College Scorecard hopefully this improves over time,” he wrote in an email. “There’s been a long-standing belief that once a student attends graduate school they are automatically blessed with better outcomes and earnings potential, but this report is highlighting that’s not always the case.”

Robinson added that the report highlights that graduate programs should not be exempt from accountability.

“There’s a clear case of students taking on large debts for programs that are not paying off,” he wrote. “If we want better outcomes for students, we need to examine higher education in its entirety and that includes graduate education.”

Itzkowitz said the report provides one piece of a bigger picture.

“I think it gives opportunities for schools to help examine the type of education they’re offering, the cost that they’re offering it at and the type of outcomes that they’re having after students obtain their graduate credential,” he said. “In that sense, this data is an opportunity for institutions, which they should use if they’re interested in improving the outcomes of their students who enroll in graduate school.”

Walden University did not respond to a request for comment about the report’s findings.

The data analysis included student debt and earnings for the two-year cohort of graduate students at 1,661 institutions and 6,371 graduate programs. At the institution level, Itzkowitz multiplied the department-provided repayment rate by the amount of federal loans owed to get the total amount of loans remaining five years later. For each individual graduate program, the analysis provided a debt-to-income ratio using median debt and median earnings data four years after students completed the program.

For example, students in Walden’s doctorate in psychology owe 243 percent more in student loans compared to their earnings four years after completing the program, according to the analysis.

“These are sort of pieces of the puzzle in terms of graduate student loan performance that we’re limited to nowadays,” Itzkowitz said. “We can get better data and we should get better data to help us evaluate how well these types of programs are actually serving students. Even with some such poor outcomes, we have very minimal if almost no laws in existence to hold these programs accountable for the outcomes of their students.”

The graduate programs at for-profit institutions as well as non–degree-granting graduate programs at other institutions would be subject to the department’s proposed gainful-employment rule that’s expected to be finalized later this year.

The Council of Graduate Schools wants to see a number of changes to federal student loans that it says would make the system more accessible to graduate students. Those changes include expanding Pell Grant eligibility from 12 to 18 semesters, which would allow students to put the funds toward a graduate or professional degree.

Julia Kent, vice president for best practices and strategic initiatives at the Council of Graduate Schools, said the council also supports reinstating subsidized direct loans for graduate students, which don’t accrue interest while the student is in school.

“That really saves students who are trying to invest in their futures thousands of dollars,” she said, commenting on the issue of graduate student debt more broadly because she hadn’t seen the report or the underlying data yet.

She said that loan counseling and financial aid education should be required for students entering a graduate degree program. Kent added that it’s important for institutions to be transparent about their graduates’ career outcomes so that students can make informed decisions when considering a program.

“Graduate students should really understand their options when they’re considering investing in a graduate degree,” she said. “There’s a huge payoff in terms of earnings and reduced unemployment for holders of graduate degrees, so we need to find ways as a country to support these investments for students and ensure that they’re not penalized for trying to advance in their careers.”