You have /5 articles left.

Sign up for a free account or log in.

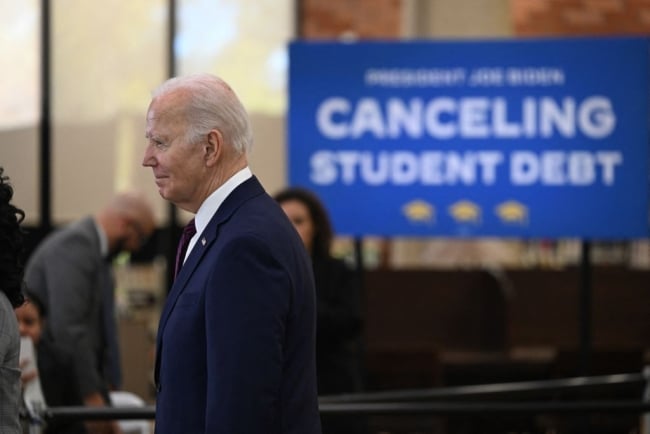

President Biden’s signature efforts to make the student loan system work better for borrowers are on hold in the courts, causing more confusion for borrowers as the grace period ends.

Andrew Caballero-Reynolds/AFP via Getty Images

The Biden administration’s yearlong grace period for federal student loan borrowers ended Monday, and advocates who work with borrowers are bracing for the worst.

During the grace period, which was aimed at easing borrowers back into repayment after the three-year payment pause, those who didn’t make payments were spared the worst financial consequences, including default. But now, for the first time in more than four years, borrowers will be able to default on their loans.

Before the pandemic, nearly 20 percent of borrowers were in default and about a million borrowers defaulted a year. About 43 million Americans hold federal student loans. Debt relief and consumer protection advocates worry that the default rates could eclipse pre-pandemic rates in nine months. Millions of borrowers haven’t had to make a payment since they left college, and federal judges put on hold new repayment plans and a plan to forgive loans for nearly 28 million borrowers, sowing more confusion and sending the system into disarray.

“I’ve been doing this for 14 years, and this is the worst I have seen the system,” said Natalia Abrams, president of the Student Debt Crisis Center, a nonprofit that advocates for borrowers. “Basically, borrowers are doing everything [they’re] being told while the system is crumbling beneath them.”

Another program known as Fresh Start, which offers borrowers who defaulted on their loans before March 2020 a quicker path out of default, was also supposed to end Monday, but the department extended it until Oct. 2 at 3 a.m. Eastern due to website issues.

Nearly 30 percent of borrowers were past due on their loans earlier this year, the U.S. Government Accountability Office found. A survey from the Pew Charitable Trusts’ student loan initiative found financial insecurity is a key reason why borrowers aren’t making payments. About one-third of borrowers who had less than $25,000 in household income were behind and not making payments, said Brian Denten, an officer with the student loan initiative. Over all, 13 percent of those surveyed weren’t current on their loans and another 12 percent reported making inconsistent payments.

“Our concern is that borrowers will be returning to a system that has never done a good job of getting them back on track,” Denten said.

Denten added that the department needs to be more proactive in communicating with borrowers about their options and how to navigate the system. Otherwise, he said that “this amount of confusion really stands to derail a lot of people financially, if it does not go well.”

Starting Tuesday, borrowers who go 90 days without making a payment will be reported to credit agencies. After nine months of no payments, they’ll default on their loans. In order to get out of default, borrowers have to pay the past-due amount, among other penalties.

“I’m most worried about a mass wave of default next year, nine months from now,” said Abrams. “There are so many borrowers … [who] graduated in 2019, 2020—they immediately went on pause. They never made a payment. They’re unfamiliar with this system. They were promised debt cancellation.”

Defaulting, Abrams added, prevents borrowers from taking out any more federal loans and “destroys your credit.” Additionally, those who default can have part of their tax refunds or Social Security checks withheld. The department also can automatically take up to 15 percent of a borrower’s paycheck, but that system is currently on hold, according to the agency’s website.

Abrams said the grace period ending without the repayment and debt-relief options in place is the worst-case scenario.

“The fear is [that default is] going to be much higher than it was previously because it’s so much more confusing and broken than it was previously,” she said.

For colleges, the return of default means that a key accountability metric is back in play. The government uses a metric known as the cohort default rate as a way to hold colleges accountable. The rate measures the proportion of borrowers at an institution who have defaulted over a three-year period, and a high rate can lead to institutions losing access to federal financial aid. The national cohort default rate was 11.5 percent in fiscal year 2017 but has sat at zero percent for the last two years, though that could change next year.

“Because so much is tied to the default rate and how significant default is for student loan borrowers in terms of having their wages garnished or their tax returns or Social Security checks offset, it really is this seismic thing in the system that does act as a foundation for a lot of how everything operates,” said Denten. “With [repayment] turning back on and the gears turning along with it, I think there could be some unexpected consequences for it happening during such a confusing time.”