You have /5 articles left.

Sign up for a free account or log in.

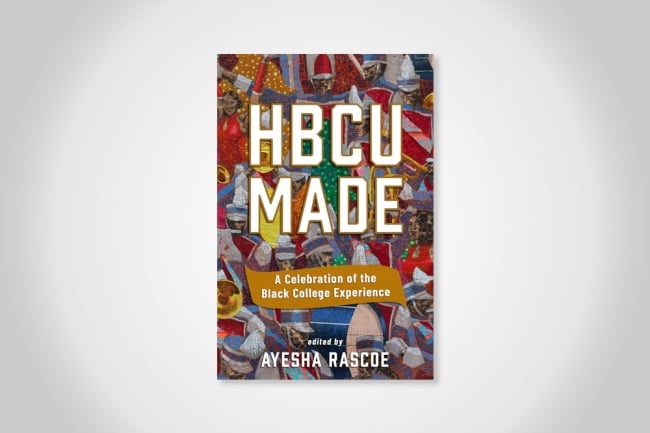

Algonquin Books

HBCU Made: A Celebration of the Black College Experience, published in January, reads like a series of love letters to historically Black colleges and universities.

HBCU alumni recount in a collection of essays the impacts these institutions had on their career trajectories and their varied understandings of Black identity. The essays’ authors range from big names, such as Oprah Winfrey and Stacey Abrams, to newly minted graduates.

HBCU Made (Algonquin Books) was edited by Ayesha Rascoe, host of NPR’s Weekend Edition Sunday and a Howard University alumna. Rascoe spoke with Inside Higher Ed about her experiences at and after Howard that motivated the book, the benefits of an HBCU education and some of the internal challenges institutions wrestle with and how societal perceptions of HBCUs are shifting. Excerpts from the conversation have been edited for length and clarity.

Q: What inspired you to put this book together? What do you hope it adds to the discourse around HBCUs?

A: I’m a proud graduate of Howard University, and the decision to go to Howard was a pivotal decision in my life. It was me stepping out, going to a place that I felt a connection to … and I always would run into graduates of HBCUs in these amazing positions who have done all this wonderful stuff and always had a love for these institutions. And so I wanted to just give a little slice of that to the world.

Q: How did you pick the range of voices you included in the book?

A: Well, I wanted a wide range of ages … I wanted to get different perspectives. I wanted, of course, Howard, Hampton, Morehouse, Spelman, but then I wanted those schools that are lesser known … So, there are a lot of the big names that everyone hears about all the time, but then there are smaller schools like Dillard and others.

Q: You write in the book’s introduction about how your time at Howard University helped you find your voice as a journalist. What was it about that environment that had that effect?

A: Being at an HBCU, you are in a place where there’s a lot of diversity. You’re in a place where there are Black people from all over the world, from all different economic groups and all sorts of different experiences. But you’re also at this place where you don’t have to question your value and no one’s looking at you and saying, “Well, you’re just here because you’re Black. Did you really earn this?” … It’s really a place where I felt like I was able to just figure out who I was without having that extra layer of dealing with finding my authority and my voice and my strength as a Black woman in a world where it’s constantly questioned. I was able to see very successful Black people, Black journalists, and I was able to be pushed to be the absolute best that I could be. And I was able to see these different people, who looked like me in a sense, but who were further along in their careers, further along in their lives—professors, deans. It gave me a sense of what I could be.

Q: Something you just touched on that struck me in the book is how many of the authors wrote about how relieved they were to put racial discrimination on pause, or at least to have it less present in their lives, during their time in college, which seems to reflect your experience as well. What’s it like to then transition out of that environment?

A: It is a safe haven in a sense … I do think that once you leave there, you’re left with the connections that you’ve made. And you’re also left with the idea that “I can take on the world” … It does resonate with me that you have this time to really just learn for yourself who you are, in the fullness of who you are, without having to be looked at through this lens of being other. And at the same time, when you leave that place, I don’t think that confidence leaves you, even though you aren’t in this safe haven anymore. Those things that you’ve learned about yourself you carry with you.

Q: Another theme that came up in multiple stories was students discovering the diversity of their peers at HBCUs, in terms of politics, religion, country of origin, sexual orientation and gender identity. Many wrote about the experience of having a collective identity as Black students but also all of these different, overlapping identities. There are ongoing conversations in the higher ed world about what diversity and inclusion should look like at predominantly white institutions. How do you see HBCUs engaging in their own version of that work?

A: There are some places where I think that HBCUs have done well, and there are some places where I think there needs to be growth.

I think that when it comes to going to an HBCU, you really see the humanity of Black people, because you recognize that Black people are not monolithic and that there are all sorts of Black people, because we’re human. And I know that sounds so elementary. But in many ways, when you look on TV and in the media, you can see Black people really portrayed as one thing. Whereas obviously white people are generally allowed to have all sorts of identities. Black people really have a much more narrow box. So going to an HBCU, you do see people from all these different countries, from the Caribbean, you have students from Nigeria, all over the place, all over the world coming to an HBCU … You have Republicans, Democrats, anything you could think of.

Michael Arceneaux, who has an essay in the book, who is a gay Black man, talks very eloquently about how he didn’t always feel supported as a gay man at Howard and how it was hard … So, when it comes to sexual orientation, when it comes to gender identity and things of that nature, I think that HBCUs, like all schools … I think there’s a ways to go. But Black people are gay, they’re trans, they’re all of these things.

Q: April Ryan writes in her essay that she’s seen a positive shift in the way that HBCUs are viewed by the wider public. Do you also see that shift, and if so, what do you think accounts for it?

A: I have seen that shift as well. Before … there was this idea among some people that going to an HBCU was limiting. Because it’s not “diverse” like the rest of the world. It’s not representative of the world outside of an HBCU. And it was kind of in some ways looked down upon.

But these days, there’s this almost attention on HBCUs, whether it was Beyoncé doing Homecoming [a documentary honoring HBCUs] or Deion Sanders going to [coach at] Jackson State for a little while. You’ve had all of these huge donations to HBCUs. And now, obviously, you have a vice president of the United States who’s an HBCU grad. Especially for the bigger HBCUs—and I think they still have to get there for the smaller HBCUs—they look at it and … there’s a cachet there … I think there’s a lot of things going on with that. It was 2020 and George Floyd and wanting to give back to Black institutions … I think there’s definitely been this resurgence and an acknowledgment of the strength and the power of HBCUs.

Q: Who do you hope reads HBCU Made, and what do you hope is the key takeaway?

A: I’d love to have high school students who are considering what school they would go to. I would love for freshmen, people who are in college at HBCUs to read it to see about those people that have come before them and that maybe they’ve gone through some similar things as well.

And you don’t have to have gone to an HBCU or be going to an HBCU to enjoy the book. I think that so many people don’t really know about the HBCU experience. And they hear it talked about, but they don’t really know why people are so amped about HBCUs, and you can read this book and find out. What I hope that people get from it is why these institutions exist and the role that they have played in shaping so many of the people who have in their own ways made the world a better place.