You have /5 articles left.

Sign up for a free account or log in.

Eleven college are participating in the first cohort of the Gardner Institute’s Transforming the Foundational Postsecondary Experience program, which is designed to help boost student success during the first two years of college.

Gardner Institute

The majority of students who stop out of college do so within the first two years. This pattern has long vexed college administrators, who’ve tended to focus their efforts on first-year students in the belief that a successful first year is key to students returning to college the following years and ultimately earning a degree.

Some colleges have also started paying more attention to second-year students as a result of research showing the importance and benefits of doing so. Eleven colleges are working with the Gardner Institute, an organization focused on improving academic outcomes, student retention and college completion, as part of a new initiative to decrease stop-outs within the first two years.

“The effort is really acknowledging and focusing on the importance of the first two years of college,” said Drew Koch, chief executive officer of the Gardner Institute.

Colleges have long focused on reaching first-year students—the Gardner Institute’s namesake even coined the term “the first-year experience.” But more recent research suggests there is value in continuing those efforts through a student’s second year, when they’re most likely still finishing general education courses and deciding on a major.

“The first year matters, but the evidence we have, based on work with hundreds of institutions, shows that so does the second year,” Koch said. “When you take the two into account and address them collectively, you are dealing with anywhere from 75 to over 80 percent of all attrition that occurs in the higher ed. That’s largely gone unnoticed.”

The institute launched its new program, Transforming the Foundational Postsecondary Experience, this summer with the goal of closing performance gaps and improving student outcomes by helping colleges analyze data about their students and redesign their student success initiatives. The institute said in a press release that this will help eliminate “factors such as demographics and zip code as the best predictors of who gets to graduate.”

There are 115,000 total undergraduates enrolled across the 11 colleges and universities—a mix of two-year, four-year, private and public institutions— participating in the program. Of those students, 43 percent receive a Pell Grant and 41 percent identify as students of color, according to data from the Gardner Institute.

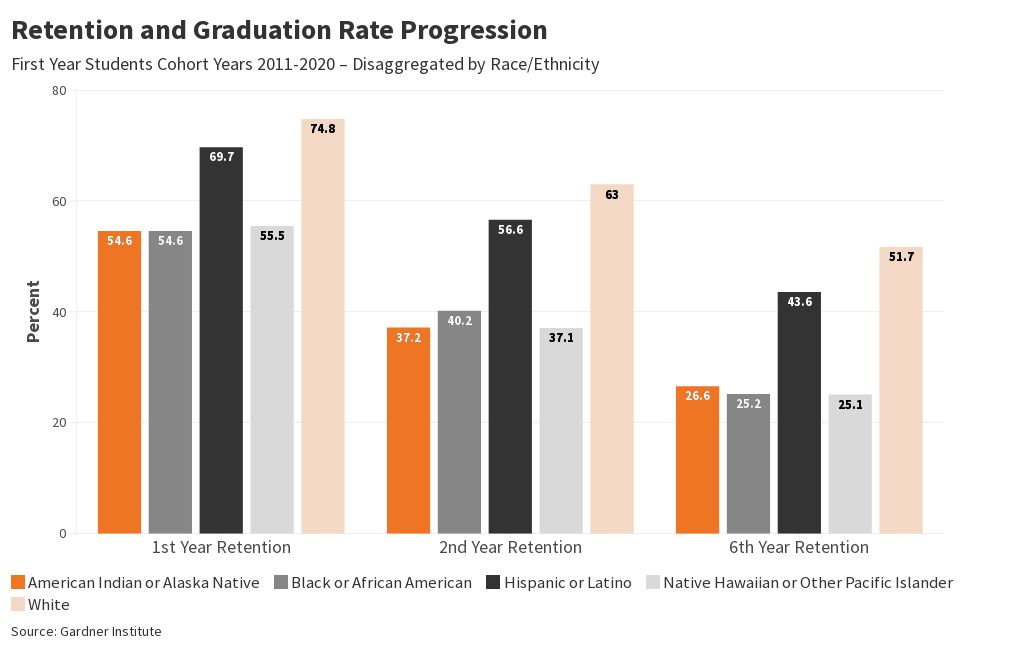

Nearly 75 percent of white students returned to college after their first year, 63 percent returned after their second year and 54 percent graduated within six years. Black and Hispanic students, however, returned at much lower rates after the first (54.6 percent and 69.7 percent, respectively) and second years (40.2 percent and 56.6 percent, respectively) and far fewer (25.2 percent and 43.6 percent) graduated college within six years.

White students have higher retention and graduation rates compared to students of color.

A Flourish data visualization by Justin Morrison (data from Gardner Institute).

Over the next five years, the institute will work with those institutions to develop long-term, sustainable plans to increase metrics of success for all students, including course completion, retention and graduation rates. While each college will come up with its own plan for how to achieve that, colleges with similar goals will form subgroups where they can exchange ideas and approaches.

‘No Quick Fixes’

But Koch said the institute’s leaders have acknowledged that moving the needle on student outcomes will take more than five years.

“There are no quick fixes,” he said, adding that he wants the colleges’ leaders to use that time frame to ask, “If race, ethnicity, family income and ZIP code are the best predictors of who succeeds—and nationally they are—then how do we intentionally move toward eliminating that?”

To help the colleges find those answers, the institute will start the first year of the program by administering a transformational assessment, which will identify the colleges’ strengths on student success and areas that need improvement. The institute will also administer a survey to gauge institutional readiness and willingness and ability to make changes. Additionally, the institute will collect student-level data to better understand the factors driving retention and graduation gaps. All these results will be presented in a series of informational meetings for the colleges, which will inform their individual plans for the remainder of the five years.

The institute expects to bring dozens more colleges into future cohorts over the next several years and estimates it will take $17.95 million to make it happen. So far, it has received about $12 million from philanthropic organizations—Ascendium Education Group, the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation, the ECMC Foundation, and the Kresge Foundation—that will fund the operational costs of the program, including research on student performance and supporting colleges through implementing programmatic and structural changes.

The participating institutions will cover remaining costs, which Koch estimates could run each college between $25,000 and $40,000 and represents institutional buy-in.

“This is about how they use limited money they already have in a wiser fashion,” he said. “A lot of time institutions are doing a half dozen to twenty dozen things, but no one is helping them pull it all together. That’s a distinct piece of this. Our goal is to make that happen.”

After each college’s plan has been implemented for a couple years, the institute will re-administer its surveys to see how well the plans are working to improve student outcomes and then refine aspects of it as needed.

“We don’t want to turn around after five years and say, ‘Did it work?’” Koch said. “Ultimately, they’ll have created and implemented to a high degree a strategic plan around student success.”

Collaboration

One of the keys to implementation is embedding those new initiatives into a college’s larger strategic plan, so they don’t change when the institution’s leadership does.

Queensborough Community College in New York underwent numerous changes that undermined efforts to boost first-year student success. Thirty percent of the college’s students currently end up with a zero grade point average after their first semester.

The college implemented programming more than a decade ago to improve academic outcomes, but it lost momentum when administrators tried to scale those programs for all students, said Christine Mangino, president of Queensborough, which is one of the 11 colleges participating in the Gardner Institute’s inaugural cohort.

“It got watered down. There were budget cuts. Faculty weren’t getting enough time to do some of the work they had been doing with students. So now when we look, it’s not there,” said Mangino, who noted that supports such as career advising have disappeared from the college’s programming.

“We’re looking to build that back up, but we also have to figure out how to scale it for the full two years, because we only have so many advisers.”

Mangino’s biggest goal over the next five years is to have 40 percent of students graduate within three years, without equity gaps. As of 2019, Asian and Pacific Islander women were the only demographic of students at the college who have reached that goal, according to data from the college.

Improving graduation rates is part of what pushed Queensborough to seek out a spot in the Gardner Institute’s program.

“The fact that they’re enabling us to use tools to assess our capacity for transformational work is exciting, so we can see where we need to put our energies to make this happen,” Mangino said.

While Queensborough administrators are still developing strategies, they’ve already met with the other colleges in the cohort during leadership workshops.

“It’s been really helpful for all of us, partly to hear that we’re not alone in this work,” she said. “But also that people are doing amazing things across the country that are showing success, so we can learn from each other.”

That opportunity to collaborate was also appealing to leaders of the University of Alaska Southeast, whose primary goal is to grow enrollment after its student head count fell from 2,297 in 2018 to 1,943 in 2023.

“We view enrollment as the result of recruitment and retention,” said Maren Haavig, the university’s provost. While university officials are already working to increase enrollment and retention rates, the opportunity to join a cohort of institutions with similar goals was appealing.

“This seemed like a way to leverage the Gardner expertise,” Haavig said, “and approach our existing—and probably some new—activities in a very coordinated and thoughtful way that we thought would be beneficial for us.”