You have /5 articles left.

Sign up for a free account or log in.

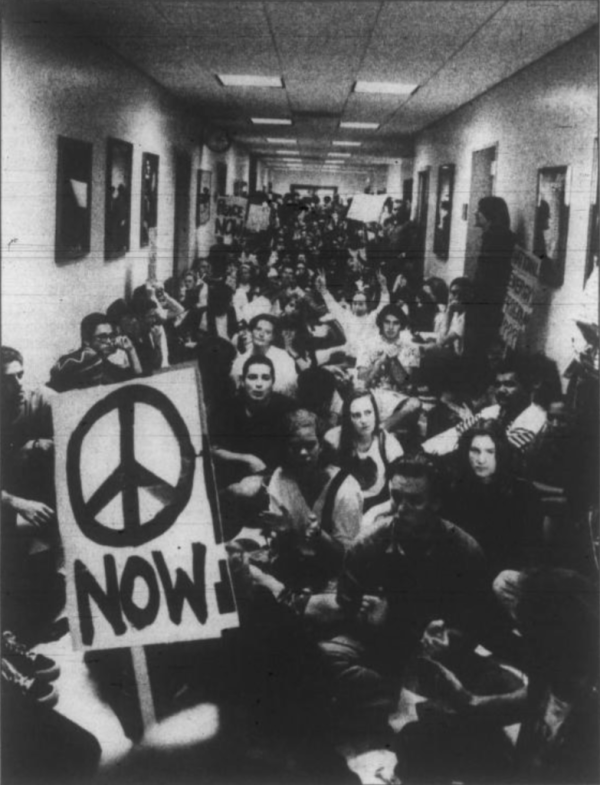

Actors play protesters in a 1991 campus demonstration for a student film at UCLA. The university denied requests to use its name or image in the film, prompting concerns about free expression.

Erica Hou

Chris Walsh was a senior at the University of California, Los Angeles, in 1991, when the world watched U.S. bombers litter Baghdad with a constellation of explosions during the first Persian Gulf War. Soon after, he joined thousands of other UCLA students and faculty in a massive antiwar demonstration.

Three decades later, Walsh’s son Kyle, a current UCLA junior, is trying to turn his father’s story into a movie for the student-led Film and Production Society (FPS). But there’s one major difference: the film won’t technically be set at UCLA.

While the students were granted permits to film on campus, the university prohibited them from mentioning UCLA as the setting, or portraying it identifiably at all. Even the central location of the narrative—Murphy Hall, where university administrators are housed and which played host to a large rally and sit-in in 1991—can’t be named.

UCLA’s decision greatly inconvenienced the filmmakers, said senior Sam Sparks, a member of FPS and the executive producer of the film. The denial was handed down just three days before shooting was set to begin, after locations had been booked and actors scheduled. The script was hastily rewritten to replace direct references to the university or its landmarks; instead of UCLA, it will be set at a nameless college campus, outside an anonymous administrative building. Editors will be required to mask or remove the UCLA name or recognizable campus buildings from all shots.

The Daily Bruin Archives

Beyond creating logistical challenges for the filmmakers, some say UCLA’s response has troubling implications for the freedom of creative and academic expression.

“Saying that to make a film about an actual event that occurred at UCLA without ever saying this is UCLA, it certainly does raise issues about academic freedom,” said Daniel Mitchell, a former professor at UCLA’s Anderson School of Management. “At the very least, it’s teaching these students the wrong lesson.”

Joseph Bristow, the chair of UCLA’s faculty committee on academic freedom, was mystified by the series of events.

“I wish I understood exactly what happened with the Film and TV Club,” he wrote in an email to Inside Higher Ed.

He added that the chair of UCLA’s Faculty Senate, Jessica Cattelino, was in touch with administrators about the decision; Cattelino did not respond to a request for comment in time for publication.

Mitchell said his main concern was that the doctrine of brand and trademark protection—which, in his mind, belongs to the realm of bootleg T-shirts and beer cozies—would be more frequently applied to student projects going forward.

“It’s different if you want to make a T-shirt or hat and stamp ‘UCLA’ on it. They will try to prevent that sort of thing, but this is kind of in a different category; you’re not really making a statement about anything,” he said. “When content gets involved, that raises some other issues.”

Bill Kisliuk, UCLA’s director of media relations, said that all student projects using the UCLA brand—a category that he said includes “name, logos, seals or other distinguishing assets”—must be approved by both the Events Office and the administrative vice chancellor’s office.

“In this instance, a student group sought to make a film that is fictional in nature and that was not part of a class project or assignment,” he wrote in an email to Inside Higher Ed. “As a general matter, UCLA does not allow use of building names or other marks in films that are commercial or fictional in nature.”

Rochelle Dreyfuss, an emerita professor at New York University School of Law who focuses on copyright law and ethics, said a recent expansion in the application of trademark law has allowed universities to limit the way their names and images are used.

“It’s really happened over the last 30 years or so, where universities have decided that they have some control over how their names are depicted [in film and television],” she said, pointing to a 1998 case in which NYU denied the television show Felicity’s request to set the story there.

UCLA’s own trademark and branding policies seem to reflect this; one policy on its website focuses specifically on “the importance of still and moving images to UCLA’s identity and brand.”

“In some contexts, a photo of Royce Hall says ‘UCLA’ as clearly as a logo,” UCLA’s brand website says.

“But that’s still different from having control over a true story that names the university,” Dreyfuss added. “So this decision is pretty far out there.”

Scott Willyerd, a managing partner at the education-focused public relations firm RW Jones, said the calculations universities make to protect their brands can be strict, even when it comes to a student project. That’s especially true, he added, for institutions with widespread name recognition.

“This is really all about an assumption of risk,” he said. “I’m sure there are other institutions out there that will say, ‘If it’s a student project, then you have free rein.’ But they’re not UCLA. UCLA is really a brand, and opening up your campus to filmmakers, even students—or sometimes, especially students—can be a risk not worth taking.”

Goodbye, Murphy Hall

UCLA’s Gulf War protests were the subject of ample media coverage in 1991, but Kyle Walsh said his intention wasn’t to document the historical moment so much as to preserve his father’s unique story through a kind of fictionalized oral history.

The film, he said, is the tale of one bright-eyed idealist’s disillusionment with activism on campus, especially after news cameras and reporters descend and the students’ once-righteous fervor begins to seem performative and futile. It’s a story that resonates with Walsh in a new age when campus demonstrations—especially against conservative speakers—are frequently covered by national media.

UCLA’s decision to deny him and his film crew the right to use the university name made the film generic and rootless, Walsh said. He even had to change the film’s original title, “Good Morning Murphy Hall”—a pointed reference to the headline of a 1991 story on the protests in the student newspaper The Daily Bruin—to the more neutral “Give Peace a Chance.”

“If somebody watches this who doesn't know the true history, they might think this is just some made-up story,” Walsh said. “On a personal level, it’s disappointing that I can’t tell my dad’s story the way I wanted to.”

Photo by Erica Hou

The Events Office, which usually handles location requests for student films, was on board with the project, Sparks said; it was only when the administrative vice chancellor and the university’s brand approval system, UCLA Marks, got involved, that issues arose.

“It’s ironic, because it really doesn’t defame the university at all; it’s not about that,” Walsh said. “But now, instead of a movie about the history of student protests on campus, the story is about us protesting for our rights as filmmakers, and for students’ right to tell stories about UCLA more broadly.”

Willyerd said that even small concerns or unknown factors can prompt a defensive response from universities worried about their brand. That’s become especially true in the age of fast-spreading digital content, he said, when it’s harder than ever for an institution to control its public image.

“Institutions have to be overly protective of their brand, because any harm to it could mean a dent in their bottom line,” he said. “As they become more concerned with their brand, we’ve also seen some become more restrictive.”

Hollywood’s Harvard

UCLA has hosted countless film crews over the years, though usually they’re professionals, working on movies produced just a few miles away in Hollywood.

According to IMDb, 95 feature films and TV movies have been filmed at UCLA as of 2022. Its idyllic greens stood in for Harvard Law School in 2001’s Legally Blonde and were the anonymous campus setting for the slasher film Scream 2. Most recently, UCLA served as the backdrop to scenes in the upcoming Christopher Nolan biopic Oppenheimer, presumably depicting the nuclear scientist’s time at the California Institute of Technology or UC Berkeley.

“The joke here is that UCLA has played Harvard more times than Harvard has,” Sparks said.

The difference with the student film is that UCLA would be playing itself. Another major difference is that those Hollywood productions usually pay a decent fee to rent out parts of the campus for shoots, whereas FPS, the student group, is financially dependent on UCLA.

“We are really reliant on funding from the student government—it’s basically our lifeline. And I think that’s meant we really don’t have the same kind of freedom,” he said. “We’re kind of at the mercy of what they say. And so ultimately, we acquiesce.”

Sparks also said he understands that the ultimate reasoning for UCLA’s decision was likely based on caution rather than aversion to the project’s content, but he and the other student filmmakers still feel slighted.

“I don’t want to ascribe any malicious intent to [UCLA]. The whole process, frankly, seems to be more of a comment on bureaucracy and liability and how frustrating that can be,” he said. “It just sends a message to students who want to make films and tell true stories about UCLA; I think it’s going to discourage them.”

“It’s disappointing, but we’re rolling with it,” he added. “As they say in the biz, the show must go on.”