You have /5 articles left.

Sign up for a free account or log in.

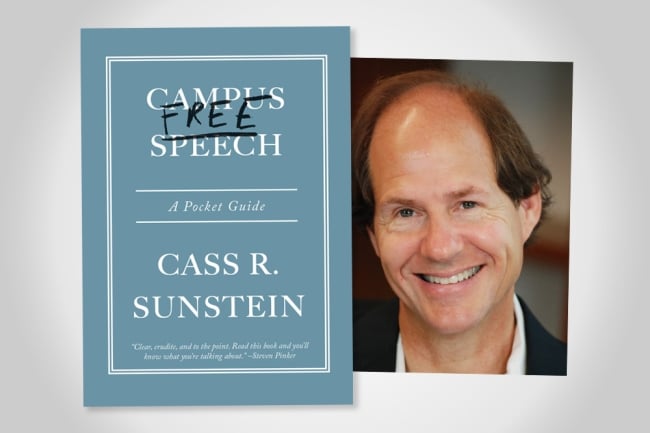

Cass R. Sunstein’s new book about free speech on college campuses comes out today.

Photo illustration by Justin Morrison/Inside Higher Ed | Harvard University Press

In Campus Free Speech: A Pocket Guide (Harvard University Press), legal scholar and author Cass R. Sunstein presents dozens of contentious free speech case studies in search of answers to what feels like an increasingly complex question: What speech can campuses regulate?

The scenarios often draw on real-life situations, such as the passage of Indiana’s new law mandating that professors provide “intellectual diversity”—which Sunstein describes as “a troubling case, and not a straightforward one”—and the incident last spring in which a pro-Palestinian student protester interrupted a dinner at the home of University of California, Berkeley, law school dean Erwin Chemerinsky and refused to leave when asked (which Sunstein concludes would warrant the student’s suspension on the grounds of trespassing).

His goal was to craft a thorough—and succinct, at just 160 pages—handbook that tackles the free speech nuances that colleges and universities might face going forward. In a phone interview with Inside Higher Ed, he discussed how he wrote the book and the key issues higher ed institutions should consider as they anticipate another fall semester rife with tensions over the Israel-Hamas war.

The interview has been edited for length and clarity.

Q: What was your goal in writing this, and especially in your choice to use case studies?

A: So, as the controversies were mounting [in the spring], a lot of people were saying, “It’s case by case,” or “Free speech triumphs,” or that universities need to provide safe spaces. I thought that the only way to get clear on this was just to write, for myself, a bunch of examples and to think about how they should be analyzed.

It was really a document that was, at first, just for myself, and I wasn’t sure if I was going to publish it or where I was going to publish it. As the real world proliferated the scenarios—and as history, as I investigated it, produced more scenarios—I thought, “This is the only way to make progress.” If you say that free speech is an absolute, or that we live in a place where dangerous speech is permitted, you may or may not be right. But you’re [being] too abstract to come to terms with the problems universities are actually facing. Or if you said that antisemitism and racism have no place on university campuses, that’s pretty abstract, and that probably doesn’t fit with our free speech principles.

It was really an effort to be a little bit like a plumber or doctor—trying to look at particular cases and see how they should be handled.

Q: One of the topics that you cover that’s especially relevant right now is the topic of incidental rules around free speech—meaning rules focused on an issue other than speech that end up impacting speech nevertheless, like policies against tents being erected on campus. What should people on college campuses know about these types of rules going into another semester of protesting?

A: A category that I think is reasonably well understood are content-neutral restrictions on speech, [such as saying] you can’t engage in extremely loud speech between the hours of 1 a.m. and 5 a.m. That’s directed at speech, and it’s content neutral. It would be subject to a kind of balancing test, meaning, is there a very good reason for it? How extensive is the interference with free speech?

An incidental restriction is a restriction that’s not directed at speech at all. So, if you say you can’t burn your draft card, the reason for that is not to regulate speech; it’s to make sure that people have their draft cards. It’s an incidental restriction on speech, because people might try to burn a draft card in order to express opposition to a war.

The Supreme Court, in a case called O’Brien, was very permissive of incidental restrictions, but it’s not a blank check. If the incidental restriction on speech is not protecting any substantial interest and is significantly impairing free speech rights, then we have a discussion. But in general, the lower courts have been following the Supreme Court’s lead, pretty permissive with respect to incidental restrictions on speech. To evaluate them, we need to know what they are, but the burden would be heavily on the speaker who seeks to get [the restriction] struck down, unlike a viewpoint-based restriction, where the burden is heavy on the person who seeks to defend it.

Q: Some protesters and free speech advocates are saying, “Yes, we know that tents are not allowed on campus. However, we see that in some historical cases, it wasn’t enforced, but it’s being enforced on us.” What are your thoughts on this? Do students have a good case that they are facing discrimination based on their viewpoints, if these content-neutral restrictions are being applied differently?

A: OK, let’s take two cases, one where there’s a prohibition on tents in some university space, and there have never been any tents in the university space, and there are tents that are favoring one point of view, and then the university starts enforcing the restriction there. That seems OK. There’s no evidence of viewpoint-based enforcement of the restriction.

If we have a university which is very tent-friendly, notwithstanding its formal policy against tents, and it has for the last 30 years, nodded, “Go for it, tent person,” and then it starts enforcing the anti-tent law against Republicans, that would not be acceptable. There you have viewpoint-based enforcement of a viewpoint-neutral [rule], and that would be very difficult to defend. The university would have to say that there’s something about the targeted tents that makes them different from the winked-and-nodded-at tents. Maybe they’re bigger, or maybe there are more people. That would be really a test of viewpoint neutrality.

Q: Another thing you discuss in the book is the Brandenburg test, which says speech that both intends to and is likely to incite lawless action is not protected by the First Amendment. There has been a lot of debate since Oct. 7 about whether specific words and phrases inherently incite violence. Obviously, “from the river to the sea” is a big one.

A: I’m in my backyard right now, my dog is looking at me, and my children could hear me if I spoke loudly. And if I said, “From the river to the sea,” I’m confident no one would engage in violence.

The context of those words could mean it’s directed to inciting and likely to incite imminent lawless action. But there’s nothing intrinsic to those words that necessarily means that, I’m confident. If I said to myself, walking from one space in Harvard Square to another space in Harvard Square, “From the river to the sea,” I would not be intending to incite lawless action and would be very surprised if there were any lawless action. I wouldn’t be vulnerable under the Brandenburg test.

If somebody says, “From the river to the sea” outside, let’s say, a synagogue on campus, with clear intention of storming the place and causing trespass and violence, that would be regulable.

For a university to say, ‘We’re not going to allow speech that makes students feel uncomfortable in their identity’ is in grave tension with [the idea that] academic institutions are places for diversity of view and for learning.”

Q: There’s also this question of hateful speech. There’s been a lot of controversy recently over Title VI protections, with some students and employees saying that hearing rhetoric they view as offensive on campus impedes their ability to get an education, and therefore it violates Title VI. Is that valid?

A: If a professor says, “Only men are allowed in my class,” that’s not protected by the First Amendment. That’s a form of discrimination. If the teacher says in class, “Asians just aren’t good at, let’s say, biology,” that might be a form of discrimination, unprotected by the First Amendment.

If a professor says outside of class something like, “Men handle math better than women,” that might well be protected by the First Amendment. But if a teacher basically makes some students feel unwelcome in the classroom, a university can reasonably say, “That’s a form of discrimination and not allowed.”

We wouldn’t want to say that Title VI broadly forbids members of an educational community from expressing views on the issues of the day. So, for a student to say, “I think Israel shouldn’t have been created,” nothing in a plausible interpretation of Title VI forbids that, and if there were a law that prohibited that statement, that would be inconsistent with the First Amendment.

Q: What about when a student says something like, “If a protest at the center of campus is opposing something that is fundamental to myself and my identity, then that makes me feel like I can’t study on campus and impedes my ability to get an education”?

A: Insofar as we’re talking about a public university, the First Amendment would not allow the breadth of the restriction implied by the idea of, “This speech is inconsistent with my understanding my identity, and it makes me feel unwelcome, and therefore it shouldn’t be allowed.” The First Amendment doesn’t carve out that kind of exception to free speech principles.

Insofar as we’re dealing with a private university, it’s not governed by the First Amendment, so it has a lot of room. But for a university to say, “We’re not going to allow speech that makes students feel uncomfortable in their identity” is in grave tension with [the idea that] academic institutions are places for diversity of view and for learning. So, if a white person hears people on campus say that whites are intrinsically racist, and that’s just how it is, that’s very unpleasant for white people to hear—many people, whatever their skin color, would disagree with that. But it’s allowed under the First Amendment and a private university would do well to allow people to discuss that proposition.

Q: According to your book, students think they’d be a lot more comfortable on campus if their universities regulated things they can’t regulate. Do you have any advice in terms of what universities can do to try to alleviate this tension, to make students feel like they can be comfortable on campus, even while doing everything they need to do to protect First Amendment rights?

A: To remember the words of Justice [Robert H.] Jackson in the 1940s: “Compulsory unification of opinion achieves only the unanimity of the graveyard.” Post that in large letters and emphasize that our university’s culture is one that welcomes views that are offensive. People used to think the idea that same-sex marriage was OK was profoundly offensive. People used to think the idea that universities should have half women and half men was a very, very disturbing idea. There are a lot of things we now believe that were thought to be horrible.

I confess that writing this book was quite painful for me. Much of my writing I find joyful, and some of this was quite painful, because the speech that I think the Constitution protects and the university should allow, some of it is horrifying, particularly about race, but to turn that distress at pluralism into something like gratitude to live in a country like ours, it turns the aspect of what are they saying to one of, “I’m so glad I live here.”