You have /5 articles left.

Sign up for a free account or log in.

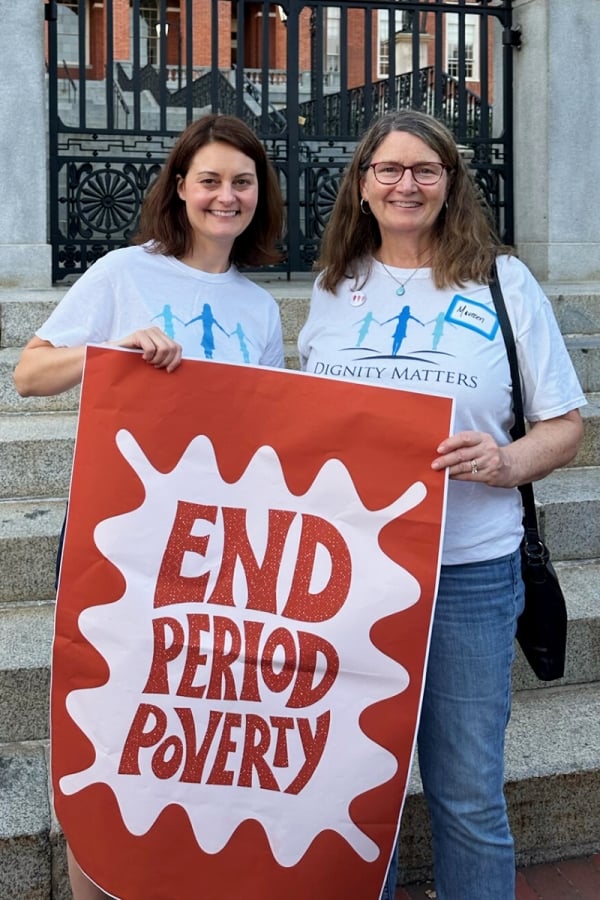

MassBay Community College currently provides period products in every bathroom across its three campuses through a partnership with the nonprofit Dignity Matters.

MassBay Community College

“Period poverty,” a lack of access to or inability to afford menstrual products, was something Elizabeth Blumberg had not heard people discuss until she attended a student government meeting at MassBay Community College in 2019.

“I go to their meetings throughout the year. One of the questions that I ask is ‘What’s working, what’s not working?’” said Blumberg, vice president of student development at the college. “When we talked about what’s not working, period poverty was brought up. It was the first time I’d heard people talk about it.”

It was an issue that no one previously wanted to discuss, but it was a common and growing problem on the Massachusetts college’s three campuses.

Once Blumberg realized period poverty was a topic of conversation among students, she knew had to act. But she and other faculty members weren’t sure how to respond.

“Our students were struggling, and we didn’t have an answer,” she said.

According to a recent survey of over 1,300 students across five university campuses, 19.6 percent of female college students said they are not familiar with the term “period poverty.” But almost as many—18.7 percent—have experienced it, reporting that they’ve had to decide between buying menstrual products and covering other expenses.

The survey, released last week by the intimate health product brand Intimina, is focused on raising awareness about period poverty and “creating menstrual equity for all,” according to a press release from the company.

The need for free menstrual products on college campuses also caught the attention of leaders of Dignity Matters, a Massachusetts organization focused on menstrual equity. After seeing shocking statistics in 2020 about the rate of period poverty among students, the leaders of the organization connected with Framingham State University and MassBay.

Dignity Matters

“MassBay responded immediately and very enthusiastically,” said Meryl Glassman, Dignity Matters’ director of development.

They immediately began to develop plans on how the two groups could work together to collect and provide free supplies in every bathroom across the college’s campuses.

MassBay and Dignity Matters are celebrating the second anniversary of their partnership this fall. They estimate that the partnership supports approximately 155 students monthly and has collected 28,344 sanitary pads, 36,850 tampons and 7,640 liners to date, about $18,000 worth of products.

Dignity Matters is just one of many programs addressing and raising awareness about menstrual products as an unmet basic need on college campuses. It was once considered a mostly “third-world problem,” but college administrators, charitable organizations and state legislatures across the country are now aware that the problem exists and are working to remedy it.

‘A Hidden Burden’

Individuals who lack access to adequate supplies of period products may improvise products or use them for longer than recommended, a practice that the American Medical Association says could potentially lead to vaginal and urinary tract infections, severe reproductive health conditions, and toxic shock syndrome.

But unlike federal public assistance programs that subsidize food and housing costs for low-income people, there are no federal programs to help pay for period products.

“Students don’t come to me for period products,” said Marybeth Fletcher, the case manager and resource specialist at MassBay. “They come to me for the basic needs that we talk most about, which is food and housing … When I can provide period products to them, they’re shocked.”

“It’s a hidden burden, a hidden basic need, because we don’t talk about it,” Fletcher added.

Jhumka Gupta, an associate professor of public health at George Mason University and co-author of a 2021 study on period poverty among college students, said historically underserved college students were more likely to experience period poverty than their peers.

“It mirrors the broader patterns that we see in health and equity research,” Gupta said.

Of the students who participated in the Gupta’s study, 19 percent of Black students and 24.9 percent of Latina students said they lacked regular access to period products in the past year. The number was lower for white students, at 11.7 percent. A similar disparity was found between first-generation students and students who were not the first in their families to go to college; 20.1 percent and 9.7 percent, respectively, reported they could not afford the products they needed.

Despite the fact that about half of the people in the world menstruate, Fletcher, the MassBay case manager; Blumberg, the administrator; and Glassman said period poverty is often the source of intense shame and secrecy—shame for being unable to pay for the products and for having a period, which is still a taboo topic in many cultures.

“The combination of those two pieces of shame really prevents a lot of women from stepping forward and saying, ‘This is a need I have, and I can’t meet it,’” Glassman said. “It’s almost like the shame gets multiplied.”

California Responded. Is It Working?

Things changed in the United States as menstruation became normalized in pop culture and advertising, women’s magazines, in schools and colleges, public health forums and various online platforms—and by women’s health advocacy groups calling on government agencies and lawmakers to make free period products more widely available.

California was the first state to introduce a law in 2021 mandating that state higher ed institutions provide free period products.

The Menstrual Equity for All Act requires all 23 California State University system campuses and 116 California Community Colleges to stock free products in at least one central location on each campus. Although the legislation doesn’t require the University of California system or private institutions to do the same, it “encourages” them to do so. The products are paid for by the state, and this year is the first when California institutions are required to comply with the law.

Cristina Garcia, a former member of the California State Assembly who authored the legislation, said implementation of the law and availability of products varies from campus to campus.

“A lot of the level of implementation has been led by the students themselves being organized and holding the campuses accountable,” Garcia said. “The student leadership for the Cal State and the University of California systems were in support and very hands-on with advocating and lobbying, and those students are the ones who went back to their campuses and aggressively pushed to implement this as quickly as possible and as robustly as possible.”

Dignity Matters

Audin Leung, an alum of UC Davis, founded Free the Period, an intercollegiate coalition that led the charge to pass California’s mandate, while a student at the university. Leung said one of the biggest pitfalls of the law is that it only requires free products in one location per campus.

“There is ongoing work to try to expand the scope of the legislation, because our ideal goal is really normalizing this as a basic product in all public bathrooms, just like toilet paper or any other basic hygiene product,” Leung said.

Sara Blair-Medeiros, associate director of the UC Davis Women’s Resources and Research Center, said despite not being included in the mandate, her campus took the initiative to add 23 period-product dispensers across campus and will be purchasing 16 more.

Blair-Medeiros said the pandemic may have slowed down some campuses’ efforts to provide the products.

“We’ve been kind of working against … not being on campus for the last three years in a more consistent manner,” she said. “Which is why things might not have necessarily moved as quickly as we would have hoped.”

Legislative Action Grows Elsewhere

According to the Alliance for Period Supplies, a consortium of independent menstrual equity organizations, 25 states and Washington, D.C., had passed some form of legislation as of August in an effort to meet the needs of students who menstruate. However, the laws vary widely, and most focus on primary and secondary schools. Only California, Connecticut, Illinois, Oregon and Washington, D.C., include higher ed institutions in their mandates. A few others, including New York, Minnesota and Hawaii, have legislation that covers K-12 and are actively working on amendments or introducing new bills to include colleges and universities. In Massachusetts a piece of legislation called the I AM Bill passed the Senate in spring 2022 but has since been stalled. It does not cover higher ed.

“There’s this thought process that, ‘Obviously, we know that middle and high school students are experiencing this,’ but people forget that somebody who’s experiencing that in high school and middle school, they’re not just going to go to college and magically going to disappear,” said Lacey Gero, the alliance’s manager of state policy. “Actually, the situation can get exacerbated.”

Gero also noted that many colleges and universities, similar to MassBay, have launched their own initiatives to address period poverty.

The University of Minnesota, for example, began providing free menstrual products in restrooms in 2007. The University of Nebraska at Lincoln began doing so in 2015. The University of Mississippi began offering the products earlier this year.

Gupta, from George Mason, said she sees the connection between period poverty and mental health as a driving force that helps get institutional leaders on board.

Gupta’s 2021 study noted the implications of period poverty on mental health. Out of 471 survey participants, 47, or 10 percent, said they experienced period poverty on a monthly basis, and 68.1 percent reported symptoms consistent with moderate or severe depression as a result.

“I think these data really helped as an additional tool in advocacy efforts for policy change,” Gupta said. “Mental health problems among young adults were already increasing pre-COVID. And now there’s a lot more attention given to that topic. If we can tie period poverty into the mental health implications, I think that’s something that university leaders could get behind.”

Gero believes there may be another reason why few state mandates on period products include higher ed.

“Sometimes the states don’t think that they have to, because some of the students are doing that work already,” she said. “But we know that that’s not a long-term solution. Certainly nonprofits and students do amazing work, but the government has to step in for a sustainable solution.”

There have yet to be any menstrual-equity bills passed at the federal level, but one has been introduced in the U.S. House by Representative Grace Meng, a Democrat from New York. It is known as the Menstrual Equity for All Act, and it does include institutions of higher education.

Massachusetts colleges would be well served by such a law. Dignity Matters provides products to about 15,000 women and girls in Massachusetts every month, “a drop in the bucket,” in Glassman’s words. She believes until there is federal regulation requiring free period products in all public spaces, it will take collaborative efforts between state and local legislatures, higher education institutions, and nonprofits to make a difference.

“We’re just really getting our arms around that here in Massachusetts and across the country, and our ability to meet that need has not caught up with the scale,” she said.