Free Download

Nearly one in five college and university chief business officers are worried their institutions are at risk of shutting down in the foreseeable future, and skepticism over the financial model of their institutions continues from last year, according to a survey by Inside Higher Ed and Gallup.

But are institutions doing enough to navigate an era of financial difficulty?

The 2015 Survey of College and University Business Officers, Inside Higher Ed and Gallup's fifth such study, reveals that as institutions deal with financial concerns, they are using some strategies, like increasing enrollment, more widely than more unpopular methods of trimming the budget. And that’s not necessarily to the benefit of struggling colleges, analysts interviewed for this article say.

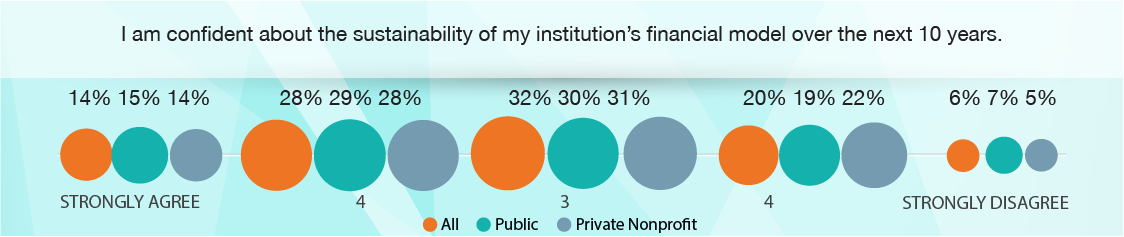

In the survey, 64 percent of business officers this year strongly agreed or agreed that their financial model is sustainable over the next five years, compared to 62 percent last year. That confidence drops to 42 percent over 10 years, roughly similar to last year’s response of 40 percent.

About the Survey

Inside Higher Ed's 2015 Survey of College and University Business Officers was conducted in conjunction with researchers from Gallup. Inside Higher Ed regularly surveys key higher ed professionals on a range of topics.

On Thursday, Aug. 13, at 2 p.m. EDT, Inside Higher Ed editors will analyze the survey's findings and answer readers' questions in a free webinar. To register, please click here.

The Inside Higher Ed survey of business officers was made possible in part by advertising from Axiom, Jenzabar and Workday. factbox ends here.

More institutions are moving toward cost-saving measures like shared services, an approach that centralizes administrative services formerly scattered across departments and schools: 43 percent reported their institutions use some type of shared services and another 23 percent said their institutions were considering adopting a shared services model.

The vast majority of CFOs said their institutions have placed a primary emphasis over the past five years on increasing enrollment (88 percent) and net tuition revenue (74 percent).

Fewer have increased their focus on measures like the cost of providing health care (67 percent) and retirement benefits (50 percent), the profitability of their academic programs (65 percent), the return on endowment investments (52 percent), the cost of athletic programs (52 percent), and increasing the faculty teaching load (44 percent).

Yet higher education analysts and experts say colleges will have to look beyond enrollment increases if they plan to solve deep-rooted financial issues in the sector.

“All of the signals are that this is a sector that is in trouble,” said Jane Wellman, a higher education finance expert with the College Futures Foundation. “Yet the kind of things that would better position institutions for the long haul probably aren’t happening. They’re still at the edges, and solving this more symptomatically than strategically.”

Increasing enrollment and net tuition revenue, as a financial strategy, “can only go so far,” said David Wheaton, the chief business officer at Macalester College, a liberal arts college in Minnesota. “Most of us are limited in how much capacity we have on our campuses,” he continued. “You can’t do that year after year after year.”

The survey, released in conjunction with the annual meeting of the National Association of College and University Business Officers in Nashville, Tenn., beginning this weekend, is based on the responses of chief financial officers at 403 public and private colleges and universities. Just under 3,000 CFOs were asked to participate in the survey. A copy of the survey report can be downloaded here.

Public vs. Private

When Sweet Briar College announced its pending closure in March -- a controversial decision that has since been abandoned after alumnae, faculty members and students fought to keep the college alive -- the news caused a ripple of concern throughout many in higher education, including business officers: Were their institutions -- many of which struggle with similar concerns of large discount rates and lowering enrollment -- also at risk of closure?

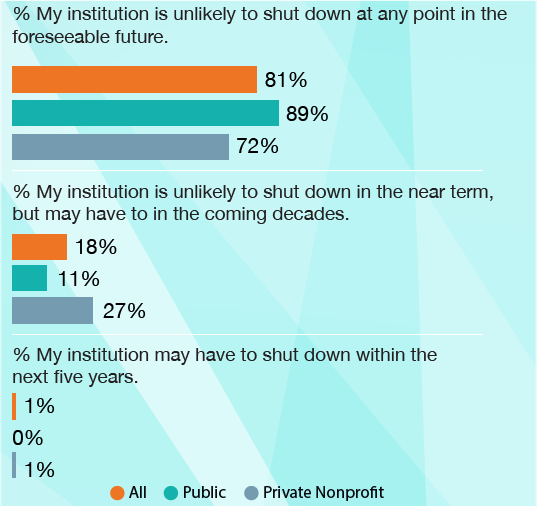

The survey, distributed before Sweet Briar's decision to shutter was reversed, found that concerns about closing aren't as rare as one might think. Nearly one in five business officers said their institutions are likely to shut down in the coming decades. Of that 19 percent, just 1 percent feared a shuttering would occur in the next five years.

“This is a sector that's in a lot of transition and it's quite unstable. The majority of the people who are responsible for money think that it's manageable in the short term, but not long-term,” Wellman said.

CFOs at private nonprofit institutions were twice as likely (27 percent) to fear closing as were their public university counterparts (11 percent), with 38 percent of baccalaureate private college business officers reporting their institutions might have to shut down in the foreseeable future.

The disparity in the number of private and public institutions concerned about shutting down was noted by several of the analysts asked to review the survey.

“That really jumped out at you,” said Richard Staisloff, a former business officer at the College of Notre Dame, whose RPK Group now consults with colleges. He says public colleges aren’t immune to the forces that contributed to the since-abandoned decision to close Sweet Briar College, a private women’s institution in Virginia.

“Demographic trends, reductions in certain revenue sources, a lack of efficiencies, a lack of response to market demand -- there are a lot of public institutions that have similar challenges,” he said.

Susan Fitzgerald, a senior vice president at Moody’s and leader of the credit agency’s higher education team, says CFOs’ responses are on par with Moody’s own analysis of the sector, which has found that about 20 percent of universities continue to confront material revenue growth pressures.

Fitzgerald says it’s rare for public institutions to shut down because their partnership with the state or a municipality kicks in during times of trouble.

“Public systems, by their nature, often have support from the state that comes in where there's trouble,” she said. ”They have that state backstop that either makes it more unlikely that they’ll close or more likely that they’ll merge.”

Public colleges are also harder to close because of the political implications of a shuttering. Many institutions are the economic driver of their towns, and in times of financial difficulty legislators tend to stymie closures.

Thirty-three percent of CFOs agree that their tuition discount rate is unsustainable -- a feeling more prevalent among CFOs at private institutions (39 percent) than at public ones (27 percent).

And while 61 percent of CFOs believe new spending at their institution will be funded by reallocating resources, rather than increasing net revenue, this feeling is somewhat less prevalent among CFOs at private institutions (57 percent) than their public peers (64 percent).

Urgency?

In the coming year, the most prevalent strategy institutions plan to focus on is increasing enrollment (82 percent), while runners-up include launching new revenue-generating academic programs (70 percent) and academic collaborations with other institutions (62 percent).

Less prevalent strategies include administrative collaborations with other colleges (39 percent), eliminating underperforming academic programs (38 percent), reducing administrative positions (38 percent) and increasing faculty teaching loads (26 percent).

The least prevalent strategies are revising tenure (14 percent), cutting athletic spending (15 percent) and outsourcing academic programs (4 percent).

“I still don't see the urgency that I would think should be there around the business model in higher education,” Staisloff said.

“There are some shifts that we see in terms of thinking differently about the business model, but not the bigger things that are necessary in my opinion to really create a robust sustainable business model for the future in higher education,” he continued. “We have to push toward more innovation and more return on investment, and that doesn't seem to be evident in the responses.”

Staisloff said CFOs and colleges, based on the survey's results, appear to be focusing more on enrollment growth and tuition gains, but should instead be focusing on items like program profitability and “increasing efficiencies and productivity within the academic portfolio.”

Of the 43 percent of institutions using a shared services model, the most common areas affected are payroll, information technology, accounts payable and accounts receivable. Human resources, risk management and procurement were also common targets. Fewer institutions used the model for grants, academic support or secretarial work.

“Shared services should be easy,” Wellman said. “Those are no-brainers.”

But shared services alone is not enough to tackle financial difficulties, she continued: “Until they tackle employee benefits and the cost structures of health care costs and start getting their academic program aligned to where student demands are, they haven't gotten to the tough stuff.”

Just 27 percent of business officers believe that they can make significant spending cuts without hurting quality.

Many institutions don’t have the data CFOs say they need to make tough decisions: 42 percent of CFOs say they have enough data to know which academic programs should be eliminated or enhanced, while 37 percent feel they have enough data to evaluate the efficacy of specific programs and majors. Thirty-five percent say they have enough data to evaluate the performance of administrative units.

A large swath of institutions aren’t doing anything to evolve their budget model to a new era in higher education: 39 percent of CFOs reported that their institutions haven’t changed their budget model in the last four years or plan to change their model in the near future.

About 24 percent of respondents use a responsibility-centered management budget model, a practice that recently contributed to deficits at arts and sciences colleges at Ohio State University and Indiana University.

Views

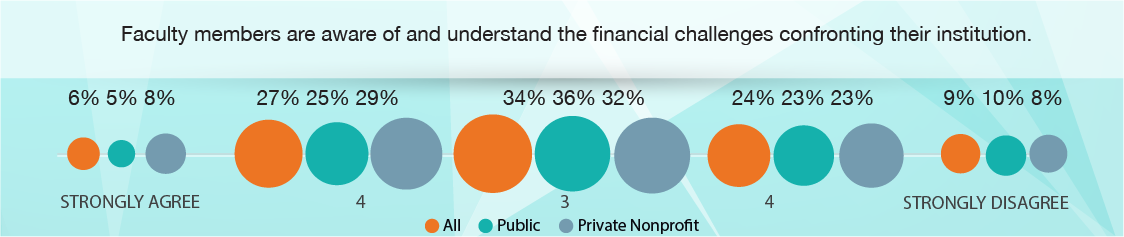

CFOs have little confidence in their faculty’s knowledge of the financial issues facing their institutions, with just 32 percent agreeing that faculty members are aware of and understand financial challenges and 33 percent agreeing that faculty members have been supportive of efforts to address those challenges.

“Business officers need to own that and do something about it,” Wellman said. “Sitting around and complaining that the faculty don’t understand is like saying, ‘It's not my problem.’ ”

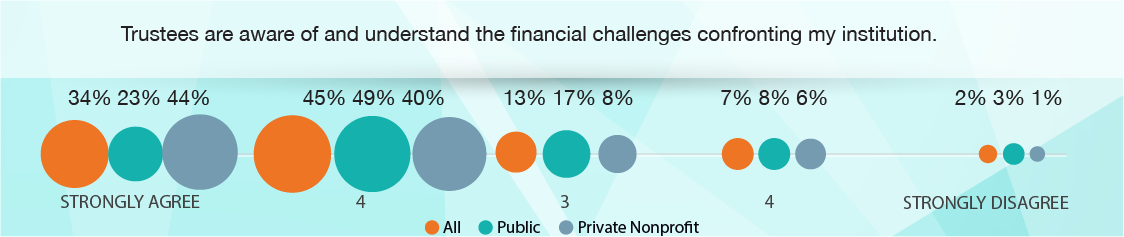

Business officers are much more confident in the understanding their fellow senior administrators (88 percent) and trustees (79 percent) have of financial challenges, and 59 percent feel that greater transparency in decision making leads to better financial decisions.

Meanwhile, 44 percent of CFOs feel that media reports suggesting higher education is in the midst of a financial crisis are inaccurate.