Free Download

Scanning the landscape, college and university financial leaders would seem to have plenty to worry about.

Student enrollments are declining, and tuition revenues along with them. Inflation is high. The federal government has turned off the tap on the recovery aid that helped many institutions weather the COVID-19 pandemic and related recession. Even colleges and universities with big endowments—those best positioned to weather financial storms—have to be nervous watching the stock market officially enter bear market territory by dropping more than 20 percent so far in 2022.

A different picture emerges, though, in the results of Inside Higher Ed’s 2022 Survey of College and University Business Officers, out today in advance of this weekend’s annual meeting of the National Association of College and University Business Officers in Denver.

While the 248 chief business officers surveyed acknowledge many of the pressures facing their institutions and express slightly less optimism than they did in last year’s survey, they are on balance upbeat about their institutions’ financial stability and largely disinclined to see the need for dramatic changes in how they operate.

Among the findings:

- About two-thirds of business officers (65 percent) agree that their institution will be financially stable over the next decade. That’s down from nearly three-quarters who responded that way a year ago, and 12 percentage points lower than the 77 percent of college presidents who answered the question that way in a March survey, but the figure reflects solid confidence even among the business officers at nonselective public and private colleges that seem most vulnerable.

- Sixty-four percent of business officers say their institution is in better shape than it was in 2019, before the pandemic hit, due in large part to American Rescue Plan funds. The third of colleges that say they’re worse off than in 2019 overwhelmingly cite lower enrollments and tuition revenue. Business officers are split down the middle on whether they’re better off now than they expect to be in a year.

- About three-quarters of business officers said their institution was either very (54 percent) or somewhat (21 percent) likely to have finished the 2021–22 fiscal year with a positive operating margin. That falls to under half (and only 26 percent very likely) excluding federal recovery dollars.

- A full half of CBOs said their institution had largely “returned to normal” operations in the wake of the pandemic; just one in six (16 percent) said their institution had made “difficult but transformative changes” in its structure and operations to “better position itself for long-term sustainability.”

- Fewer than a quarter of business officers say senior leaders at their institution have had serious discussions about merging or consolidating academic programs or administrative operations with another institution.

Those responses left some financial experts suggesting that the business leaders “may be wearing rose-colored glasses,” as Lucie Lapovsky, a consultant and former college president and CFO, described it.

More on the Survey

Inside Higher Ed’s 2022 Survey of College and University Business Officers was conducted by Hanover Research. The survey included 248 chief business officers from public, private nonprofit and for-profit institutions. A copy of the report can be downloaded here.

On Wednesday, Aug. 10, Inside Higher Ed will present a free webcast to discuss the results of the survey. Please register here.

The Inside Higher Ed Survey of College and University Business Officers was made possible in part by advertising support from ECSI, EY Parthenon and Syntellis Performance Solutions.

Added Paul N. Friga, a management professor at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill and consultant to the Association of Governing Boards of Universities and Colleges, “I don’t get the overarching optimism given the headwinds out there and the fact that many of them don’t have positive operating margins. There still seems to be this feeling that ‘we’ll just get by somehow.’”

The Financial Outlook

The centerpiece of Inside Higher Ed’s annual business officers’ survey is a question designed to gauge their overall confidence in their institutions’ financial stability over five and 10 years. Their confidence fell sharply at the onset of the pandemic but spiked last year (with 84 percent expressing confidence over five years and 73 percent doing so over 10 years) as many institutions appeared to have weathered the worst of the pandemic impact with the help of federal aid and the slow return to physical campuses. (More recently, Inside Higher Ed’s survey of college presidents in March showed college chief executives as similarly bullish, with 77 percent confident in their college’s financial outlook over a decade.)

In this year’s survey, CBOs’ confidence ebbed somewhat. Seventy percent of business leaders agreed with the statement “I am confident my institution will be financially stable over the next five years,” down from 84 percent last year; 65 percent agreed when asked to look out over 10 years, down from 73 percent a year earlier.

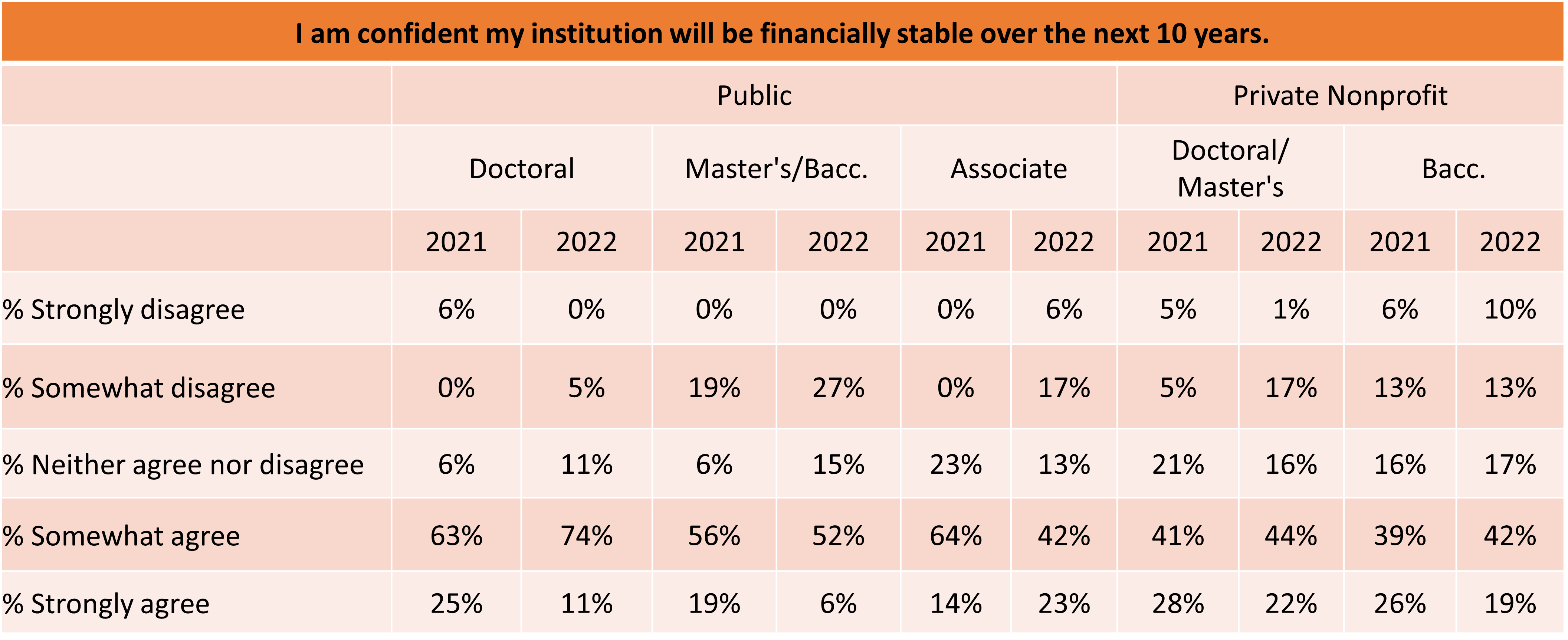

The answers vary significantly by region and institution type. Three-quarters (75 percent) of business officers in the South expressed confidence in their institution’s financial stability over a decade, while roughly three in five CBOs elsewhere did so. And a full 85 percent of business leaders at public doctoral institutions agreed that their institution will be financially stable over 10 years, compared to fewer than two-thirds of business officers in all other sectors.

The changes from a year ago also differ by sector, with significantly fewer business officers at public four-year universities strongly expressing confidence in their 10-year stability and more CBOs at community colleges and private nonprofit doctoral and master’s universities disagreeing that they are confident in their 10-year outlook.

Business officers pretty unanimously agreed that their institutions are in better shape than they were pre-pandemic, with a majority from every sector concurring.

Just 52 percent of financial leaders at public doctoral leaders and 58 percent of those at community colleges agreed, though, compared to more than two-thirds of CBOs at other public four-year institutions and all private institutions.

A full three-quarters of CBOs who agreed that their institutions are in better shape attribute that to the funds they received from the American Rescue Plan, with half or fewer citing any other reason. (Fifty percent say they reduced their expenses and their budget remains smaller, and a similar proportion said their endowment has increased.)

Those who said their institution is in worse shape than it was in 2019 overwhelmingly cited lower enrollment and tuition revenue. About two in five CBOs said they’ve been unable to make enough budget cuts (40 percent) and cited reduced auxiliary funding (37 percent).

Perhaps the most interesting divisions came when CBOs were asked what’s immediately ahead for their institutions. Slightly more agreed (42 percent) than disagreed (37 percent) that their institution is in better shape now than it will be next year, but with relatively few feeling strongly either way.

Sector differences are stark, though. More than half of chief business leaders at nondoctoral public institutions (two-year and four-year) expect to be in worse shape a year from now, while those at private and (especially) four-year doctoral institutions are likelier to expect to be better off next year than they are right now.

Business officers were asked why they answered as they did, and the top answers are below. Those who expect to be better off next year than they are now appear to be banking on improved enrollment. That may be a reasonable expectation for selective institutions like most of the public doctoral institutions, but it seems an iffy bet for others.

The CBOs who anticipate being in worse shape next year than they are now seem to be reading the tea leaves in the broader economy, expecting that government efforts to raise interest rates won’t sufficiently blunt inflation and that their institutions will have reached the end of the lifeline they received in the form of federal recovery act funds.

Recent Financial Performance

As business officers gauge where their institutions are and where they might be headed, what do they say about their actual financial performance?

Not surprisingly, given the economic turbulence of this decade so far, about two-thirds said that their revenue had declined in the two fiscal years since the pandemic began. Relatively few reported hefty decreases: about 15 percent said their institution had seen a drop of more than 10 percent, with about a quarter each placing their declines at 5 percent or less or between 5 percent and 10 percent.

Nonprofit institutions like most colleges and universities typically seek to at least break even and strive to cut their expenses when their revenues decline so as not to eat into their reserves or accumulate deficits.

Roughly three-quarters of surveyed business officers reported that their institutions achieved a positive operating margin in fiscal 2020–21, when significant federal recovery dollars flowed to them and many institutions froze salaries and imposed other emergency measures to cut their budgets.

The survey also asked business officers how likely their institution was to run a surplus in the 2021–22 fiscal year, which for most institutions ran through June 30. (The survey was conducted in May and early June.) About three-quarters said they were either very (54 percent) or somewhat (21 percent) likely to do so, ranging from 67 percent of CBOs at private baccalaureate colleges to 89 percent of business leaders at public doctoral universities.

But the picture looked different when excluding federal recovery dollars from the mix. Then, more business officers in every sector but public doctoral institutions said they were “not likely at all” to be in the black than said they were “very likely” to be so. The margin was about three to one at community colleges and public master’s and baccalaureate colleges.

Doing the Math

Business officers’ self-reported dependence on federal recovery funds to counterbalance revenue declines and enrollment losses made some financial experts question the CBOs’ optimism about their financial outlook.

Susan Fitzgerald, associate managing director for global higher education and nonprofits at Moody’s, the credit rating agency, said the roughly 70 percent of business officers who projected their institution as financially stable over the next five years is “consistent with our regular findings that 20 to 30 percent of institutions are under more fundamental financial strains.”

But while federal relief funds and strong endowment returns (for those institutions fortunate to have meaningful endowments) have left many colleges better off than they were before the pandemic, Fitzgerald added, “those that were confronting significant market challenges before the pandemic will continue to do so. This will be exacerbated if inflation continues, impacting both the affordability of higher education for students as well as the budgets for colleges and universities.”

Layer on the fact that enrollments have arguably hit a new lower plateau in the wake of the pandemic—“and data that show a continuing decline in high school graduates along with increasing skepticism about the value of a college degree,” Lapovsky said—and the many tuition-dependent colleges in the country are likely to feel intense pressure to continue to discount their tuition in ways that are widely viewed as unsustainable, she said.

Mind-Set and Actions Post-Pandemic

Most of the higher education finance experts who reviewed the survey data believe that many colleges will need to think and behave differently if they are to thrive in an era of constrained resources. They were heartened by the agility many colleges and universities showed during the pandemic and by the fact that many leaders expressed a need to make significant changes in how they operate.

In Inside Higher Ed’s 2020 survey of business officers, for instance, nearly half of CBOs said they believed their institution should use the pandemic to “make difficult but transformative changes in its core structure and operations to better position itself for long-term sustainability”; a quarter said they thought their institution could “ride out the current difficulties and return more or less to normal within 12 to 18 months.”

This year’s survey asked business leaders a version of that question, and the results were more than flipped. A full half of CBOs said they believed their institution had returned to normal, while just 16 percent said their institution had made the sorts of difficult but important changes necessary for long-term sustainability. Community college business officers were likeliest (22 percent) to say they had undergone meaningful transformation, compared to just 6 percent of those at public doctoral universities.

A look at the actions chief business officers said their institution had (and had not) taken in response to the pandemic largely supports that finding.

Yes, many CBOs (57 percent) said their institution had significantly increased the proportion of courses delivered online/remotely, and at least a third of those said they would sustain those increases through the next academic year. The only other action that more business officers (65 percent) said their institution had undertaken was increasing the investment in mental health services, which more than 60 percent said they would sustain going forward.

But of the list of more than 20 possible post-pandemic actions that CBOs were presented with, they were far likelier to say they had taken steps to increase revenue (50 percent, including 60 percent of private nonprofit colleges, said they had increased tuition) or to try to bolster enrollment (45 percent said they had increased grant aid, and 35 percent said they had extended test-optional admissions policies) than to have embraced more structural or operational changes. Roughly 10 percent said they had altered existing plans to build new campus facilities or increased faculty teaching loads, and between a quarter and a third said they had created new certificate programs or new degree programs aimed at nontraditional student populations.

The same pattern emerged when the business officers were asked which of the pandemic-era actions they took will be kept in place during the 2022–23 academic year—48 percent said they would continue to increase tuition, while 28 percent said they would continue to increase the number of employees working remotely, and the proportion of CBOs who said they would continue to create new academic programs aimed at new audiences declined.

“I see a real disconnect on strategies here,” said Friga of UNC and AGB. “The CBOs say they want to make institutional change, but there seems to be little appetite to cut costs, to really review which academic programs are not right for the current market or to address the overbuilding of campuses. It’s going to be hard to find revenues to invest in new initiatives without leaner operations and smaller campuses.”

Mergers and Consolidating Programs

One strategy that some colleges and universities have embraced to position themselves for the future is to team up with other institutions, either wholly (through merger) or through collaboration. Business officials suspect relatively few will go the first route, but that more might pursue the latter.

Just 9 percent of business officers report that senior administrators at their college have had serious internal discussions in the last year about merging with another college or university. Even fewer, 6 percent, say their institution is likely to merge into another college within the next five years, but 13 percent say their institution is very or somewhat likely to acquire another college or university in the next five years.

One in six CBOs, 16 percent, say their institution should merge with another institution over that time frame. Nearly a quarter (22 percent) of those at private nonprofit institutions say that, while just 9 percent of those at public institutions did so.

More chief business officers see their institutions combining academic programs or sharing administrative functions with a peer. About four in 10 CBOs say their institution is either very (9 percent) or somewhat likely (32 percent) to share administrative functions with another institution in the next five years, while 30 percent say they expect to combine academic programs with another college.

CBOs are split down the middle on whether their institution should combine academic programs with another institution, with solid majorities of business leaders at public master’s and baccalaureate universities and private baccalaureate colleges agreeing.

Lapovsky said she wasn’t surprised at the lack of expressed interest in mergers, given that most of the institutional combinations to date “have not been mergers but rather takeovers of weak schools by strong schools. There have been few recent mergers of equals.”

Academic and Business Continuity

If the COVID-19 pandemic taught colleges and universities anything, it might be the importance of being able to continue operating even in the event of a catastrophic circumstance (a hurricane, a wildfire, a campus shooting). Many institutions have long understood this on the administrative side of the house and have adopted business continuity plans. But the widespread shuttering of campuses in March 2020 has put the idea of academic continuity front and center.

The survey data reveal that about a quarter of institutions had academic continuity plans in place before the pandemic, but they became much more common afterward.

While slightly more than half of CBOs whose institutions had academic continuity plans in place before the pandemic rated those plans as either excellent (19 percent) or good (34 percent), that figure climbed to six in 10 among those who have them now.

Other Findings in the Survey

Endowment growth and changes. While the stock market has tumbled in recent months, a majority of business officers whose institutions have endowments said those funds increased during the past year. Sixty percent said their endowments grew significantly (22 percent) or somewhat (38 percent), while just 13 percent said they had decreased. The rest said the funds remained roughly the same size.

About one in seven business officers (14 percent) said their institution had withdrawn funds from its endowment over and above the levels called for under its normal spending policy. Of those, 70 percent said the amount of the unexpected distribution was less than $5 million. A quarter (26 percent) said it was more than that.

Impressions of other campus leaders. Business officers overwhelmingly agree that fellow administrators (91 percent, 59 percent strongly) and trustees (90 percent, 54 percent strongly) at their institutions “are aware of and understand the financial challenges confronting my institution.” But CBOs are more likely than presidents to strongly agree that trustees “get it” (54 percent versus 38 percent of presidents) and less likely to say that about other senior administrators (59 percent versus 70 percent of presidents).

About half of business leaders say that faculty members understand the financial challenges facing their institutions.

Data and analytics as a tool (and impediment). Roughly six in 10 chief business officers say their institution has the data and other information it needs to make informed decisions in a range of areas on their campus. They are most likely to report that their institution has the data it needs to make informed decisions about which academic programs should be eliminated or enhanced (70 percent), but they are the least likely to report that they have the data to gauge the performance of each administrative unit on campus (60 percent).

Business officers are split on whether a lack of data and analytic capacity is an obstacle to their institution’s financial sustainability (37 percent agree, 44 percent disagree).