Free Download

Even as COVID-19 slowly eases its grip on colleges and universities, campus leaders would seem to have plenty to worry about. Enrollments have fallen sharply since the beginning of the pandemic, the federal government has closed the spigot of generous recovery aid and political intrusion into curricular matters and college governance is on the rise.

Higher ed leaders seem unfazed, though: Inside Higher Ed’s 2022 Survey of College and University Presidents finds them upbeat and generally confident that their institutions are prepared for what’s ahead.

Most notably, they are optimistic about their institutions’ financial situation: more than three-quarters of respondents agree that their college will be financially stable over the next decade, most think their institution is in stronger shape now than it was a year ago and a majority believe it will be better off next year than it is now.

Presidents and chancellors recognize that the pandemic has altered the higher education landscape in key ways: more than two-thirds (71 percent) say their institution must fundamentally change its business model or other operations, and 91 percent agree (52 percent strongly) that their college or university will keep some of the COVID-19–related changes it made even when the pandemic ends. More agree (50 percent) than disagree (34 percent) that the pandemic will cause a shift toward more virtual instruction “for years to come.”

But campus leaders seem less sure about the likelihood and degree of such transformation. Three in five agree that their institution has settled into a “new normal” despite the continuing pandemic. Only about a quarter say their institution has had “serious internal discussions” about consolidating some of its programs or operations with another college or university’s.

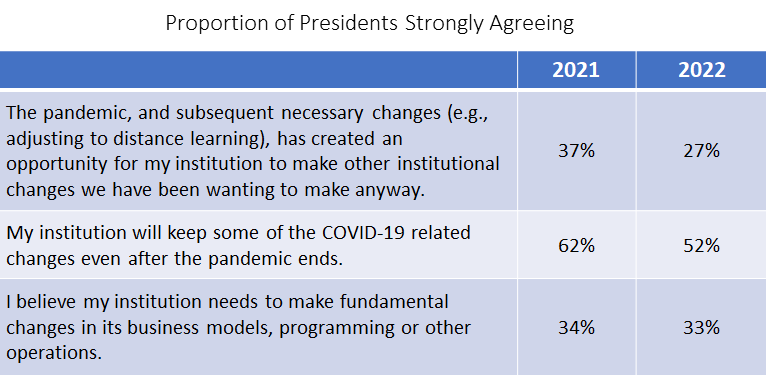

And only a quarter (27 percent) strongly agree that the pandemic-era changes have “created an opportunity for my institution to make other institutional changes we have been wanting to make anyway.” That figure was 37 percent a year ago, in the throes of the pandemic.

Among other highlights of the survey of 375 college chief executives, conducted by Hanover Research on behalf of Inside Higher Ed:

- Two-thirds of presidents say their institution has sufficient capacity to meet the mental health needs of undergraduate students; fewer say the same about graduate students and employees.

- A majority of campus leaders say that fewer than a quarter of their nonfaculty employees are working remotely this spring, and about three-quarters say the proportion of remote workers has decreased (50 percent significantly) since the 2020–21 academic year. About half say their institution has altered its employment policies to give employees more flexibility about when and how they work after the pandemic ends.

- Three-quarters of presidents rate the quality of the in-person courses at their institution this semester as excellent. A quarter (27 percent) say the same about their hybrid courses, and just 19 percent rate their fully online courses that way.

- About eight in 10 campus leaders say their institution is unlikely to shrink its physical campus in the next five years. About a quarter of community college leaders say they are likely to do so.

- Most presidents (85 percent) say their institutions have not had serious high-level discussions about merging with another college or university. Leaders at private nonprofit colleges are twice as likely as their public college peers (20 percent versus 11 percent) to say that.

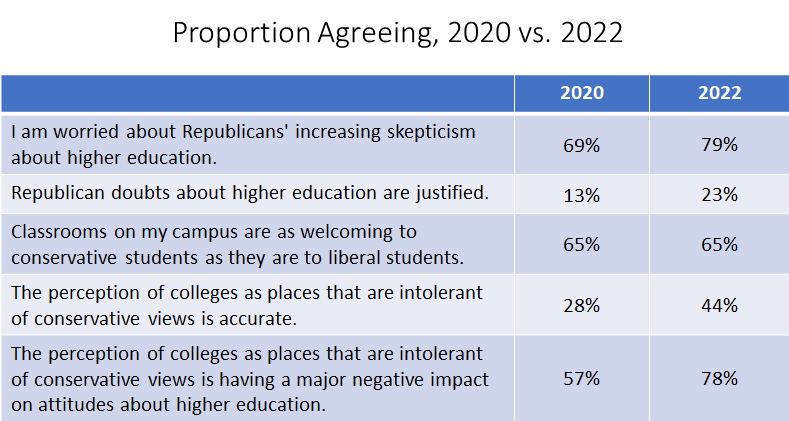

- The vast majority of respondents (nearly 80 percent) express concern about Republican skepticism regarding higher education. A growing plurality (44 percent) agree that the “perception of colleges as places that are intolerant of conservative views is accurate.”

- And, in a finding that each year befuddles many observers, presidents continue to perceive race relations on their own campuses as being either excellent (10 percent) or good (63 percent), while barely a quarter say race relations are good on college campuses nationally.

More on the Survey

Inside Higher Ed’s 2022 Survey of College and University Presidents was conducted by Hanover Research. The survey included 375 presidents from public, private nonprofit and for-profit institutions. A copy of the free report can be downloaded here.

On Monday, March 7, Inside Higher Ed will conduct a session on the survey at the American Council on Education annual meeting in San Diego.

On Wednesday, March 30, Inside Higher Ed will present a free webcast to discuss the results of the survey. Please register here.

The Inside Higher Ed Survey of College and University Presidents was made possible by support from Qualtrics, TimelyMD, Wiley University Services, EY Parthenon, D2L and the Honor Society of Phi Kappa Phi.

Justifiable Confidence or Irrational Exuberance?

The centerpiece of Inside Higher Ed’s annual survey of presidents, now in its 12th year, are questions we ask yearly gauging campus leaders’ sense of their institutions’ financial stability over five and 10 years. Responses to those questions offer a snapshot of how presidents and chancellors view their institutions’ positions in the near and midterm, much as a consumer confidence survey does.

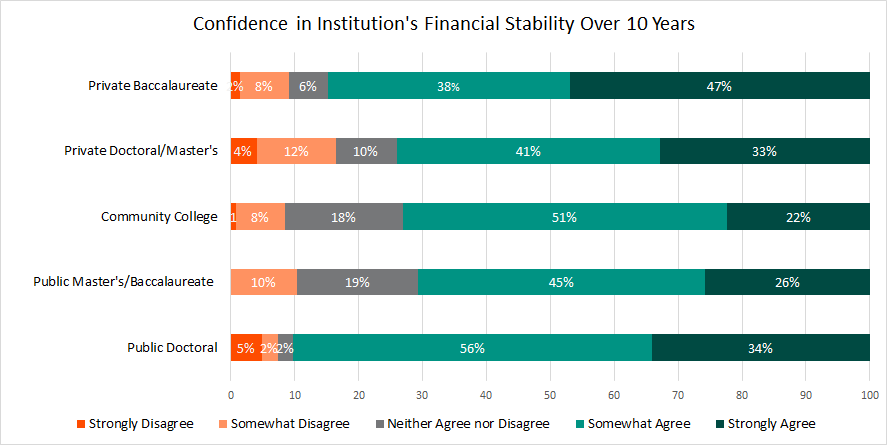

This year, as last year, most presidents expressed confidence in their institution’s stability, with 77 percent agreeing (31 percent strongly) that they are confident in their institution’s financial stability over the coming decade. But significant differences emerge at the sector level, with 90 percent of public doctoral university presidents and 85 percent of leaders of private baccalaureate colleges expressing confidence; the latter do so most strongly, with 47 percent of four-year private college leaders strongly agreeing (up from 27 percent a year ago).

Those at public master’s and bachelor’s institutions and community colleges are less likely to feel sanguine about their financial futures, but by far they are more confident than not.

Presidents of colleges in the Northeast (69 percent) were less likely than their peers elsewhere to express confidence in their 10-year outlook, with those in the South (83 percent) most likely. College leaders in the Midwest were surprisingly buoyant, at 79 percent, with those in the West at 73 percent.

Not only does the pandemic seem not to have shaken the presidents’ confidence, but many appear to believe that it has improved their institutions’ situations. Many have benefited from the substantial infusion of federal recovery aid funds, the fact that most campuses have reopened and are again receiving significant revenue from auxiliary enterprises such as housing and dining, and better-than-expected revenue from endowments and fundraising (and from state budgets for many public colleges).

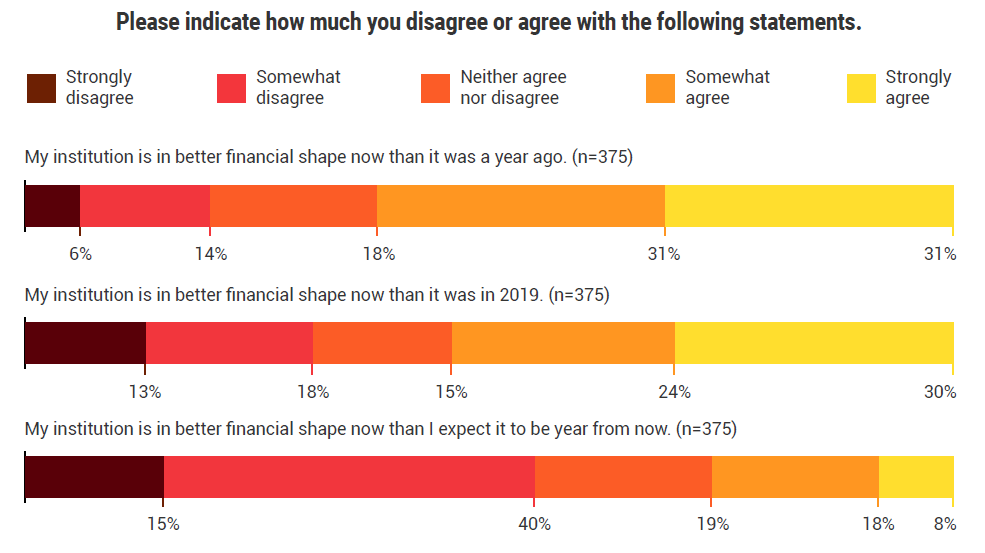

As seen in the series of charts below, presidents are almost three times as likely to agree as to disagree that their institutions are in better shape than they were a year ago and almost twice as likely (54 versus 31 percent) to agree that they’re in better shape than they were in 2019.

And they seem to reject the idea that another shoe is about to drop: while 26 percent agree with the statement that “my institution is in better shape now than I expect it to be a year from now,” 55 percent disagree. Community college presidents are more divided, though: 35 percent agree that their institution may be in worse shape a year from now, while 47 percent disagree.

The presidents’ upbeat assessment of their finances aligns in many ways with those of the ratings agencies like Moody’s, Fitch and Standard & Poor’s, all of which have predicted stability for college and university finances in 2022—assuming inflation doesn’t rage out of control and COVID doesn’t return with a vengeance.

The results also may be influencing the degree to which campus leaders are viewing whether and how much their institutions need to alter how they operate.

Viewing this year’s results on their own, presidents generally perceive that higher education is in a state of flux and that their colleges must adapt.

Fully half agree that “COVID-19 will cause a shift in enrollment trends for years to come, with more prospective students favoring virtual instruction.” Community college presidents (67 percent) and leaders of public master’s and baccalaureate institutions (57 percent) are far likelier than those at private colleges (36 percent) to believe that.

More than two-thirds of presidents (71 percent) agree that “my institution needs to make fundamental changes in its business models, programming or other operations,” and significant majorities believe that the pandemic pushed them in that direction: three-quarters agree (27 percent strongly) that the “pandemic, and subsequent necessary changes (e.g., adjusting to distance learning in the spring and fall), has created an opportunity for my institution to make other institutional changes we have been wanting to make anyway.” And 91 percent say they will “keep some of the COVID-19–related changes even after the pandemic ends.”

But in most of those cases, the presidents were less likely to agree with those statements that they were a year ago, suggesting a growing sense of returning to a “normal” that may not result in significant upheaval.

The biggest changes in those views were found among the campus leaders who expressed the most confidence in their financial stability. Presidents of private baccalaureate colleges were far less likely (68 percent this year compared to 82 percent a year ago) to believe that the pandemic created an opportunity for their institution to make other changes its leaders had wanted to make. And presidents of those institutions and of public doctoral universities were 10 percentage points less likely this year than a year ago to say their institution needs to make fundamental changes in its business models or other operations.

Presidents are also far less likely to agree this year (29 percent) than they were last year (42 percent) that “COVID-19 will cause a shift from more expensive colleges to more affordable ones, such as community colleges.” The biggest drop by far occurred among community college leaders themselves, from 69 percent in 2021 to 41 percent this year—likely influenced by the fact that the institutions have seen declines, not upturns, in enrollment during the pandemic.

What changes do presidents say they are most inclined to sustain after things turn to whatever the new normal looks like?

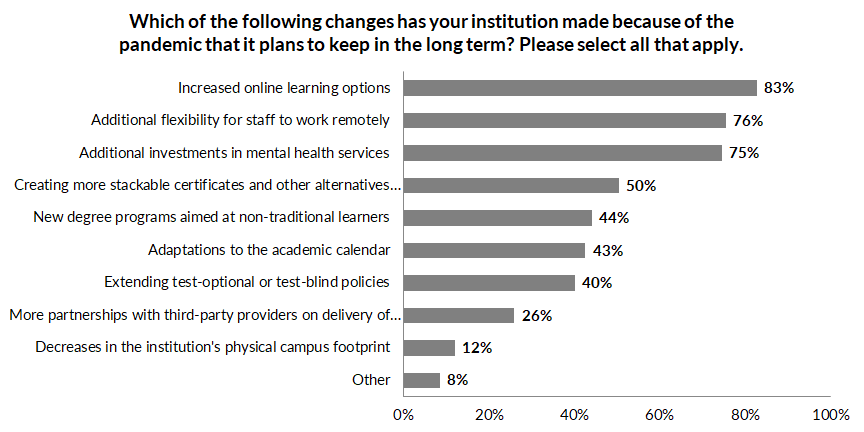

At least three-quarters of leaders plan to keep offering increased online learning options, additional flexibility for remote staff work and greater investments in mental health services. Significant pluralities say they’ll continue creating more alternative credentials (50 percent, with community colleges, at 64 percent, much likelier to say this), new degree programs aimed at nontraditional learners (44 percent), adaptations to the academic calendar, and extending test-optional or test-blind policies (40 percent, led by about two-thirds of public doctoral universities and private doctoral/master’s institutions).

About a quarter say they’ll expand partnerships with third-party providers on delivery of academic programs and other services, and just one in eight say they’ll decrease their campus’s physical footprint.

Presidents’ answers to several other questions revealed tension between their sense that their campuses need to change and their unwillingness to shake up the status quo too much.

For instance, more than half of presidents say their institutions should combine academic programs with those of another college (56 percent) or share administrative functions with another institution (54 percent) within the next five years. But significantly fewer (44 and 45 percent, respectively) said their institutions were likely to take those steps, and just 25 percent said senior administrators at their institution had had serious internal conversations in the last year about combining programs or operations with another college or university.

Fewer than one in six presidents (15 percent) say senior administrators at their institution had had serious internal discussions in the past year about merging with another college or university, though the figure was higher (20 percent) at private nonprofit colleges than at public ones (11 percent). Presidents were two and a half times likelier to say their institution was likely to acquire another institution in the next five years (20 percent) than to say it would be acquired (8 percent).

Going Digital? Not So Much

Campus leaders also seem ambivalent about the extent to which their own campuses are likely to be affected by the slow, steady shift to a more digital future—a shift that by most accounts has been accelerated by COVID-19.

As noted above, half of presidents said they believed students would increasingly seek to enroll in virtual courses in the years to come, and most (83 percent) reported that they would sustain the increased online learning options they embraced during the pandemic.

But asked what proportion of their institution’s courses are being delivered in in-person, hybrid and fully online formats this spring, presidents on average said that two-thirds of their courses were being delivered in person (64 percent), with the rest divided roughly between fully online (21 percent) and hybrid (15 percent). The in-person proportion was slightly lower than they estimated it was in 2019—71 percent.

Asked to predict what the proportion would be next spring, presidents on average expected the in-person share to continue to rebound to 68 percent.

The presidents’ sense that online learning won’t necessarily grow at their institution in the near term may result in part from their view of consumer preferences. Presidents overwhelmingly agree (84 percent, 29 percent strongly) that parents and students are disinclined to pay as much for virtual learning as they are for in-person learning.

Campus leaders’ own preferences and biases may influence their views as much as student and family expectations, though.

Asked to rate the overall/average quality of the online, hybrid and in-person courses their college or university is offering this spring, every single president rated the in-person courses as either excellent (73 percent) or good (27 percent), while 22 percent judged their online courses to be either fair (19 percent) or poor and 17 percent said that about their hybrid courses. There were virtually no differences among presidents in different sectors.

Roughly similar patterns appear when it comes to changes in the academic workplace.

Four-fifths of presidents (81 percent) estimated that fewer than a quarter of their nonfaculty employees were working remotely this spring, with 21 percent of leaders saying that none of their employees were doing so. Community college leaders (32 percent) were likeliest to report no employees working remotely.

Half of presidents said that significantly fewer employees were working remotely this academic year than in 2020–21, while another quarter said somewhat fewer employees were doing so.

The vast majority of presidents said their college or university had either already altered its employment policies to give employees more latitude to work remotely (47 percent) or was considering doing so (34 percent). Yet they clearly don’t think whatever shifts might lie ahead will be enough for them to consider reducing their campus’s physical footprint: fewer than one in five leaders say they are either very (7 percent) or somewhat likely (11 percent) to reduce the size of their campus in the next five years.

Several former college presidents and others who reviewed the survey’s findings said they were struck—and in some cases perplexed—by the presidents’ optimism.

Dale Whittaker, former president and provost at the University of Central Florida and now a senior program officer at the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation, said it seemed clear that the presidents’ sense of their financial situation had been buoyed by the federal stimulus funding, given that nearly two-thirds say they’re in a better position than they were a year ago.

As for their optimism about the future, Whittaker attributes that in part to psychology after two years of pandemic- and recession-driven worry. “I read this as people were pretty much on a high, saying, ‘Whew, we got through that, and it’s starting to feel normal again,’” he said. “What you may have got here was what they felt, not their pure intellectual assessment. It just feels so much better after being under so much pressure.”

Lucie Lapovsky, a former private college president and chief business officer who now consults with colleges on financial and governance matters, said she believes that “more change will be necessary than is indicated by the results of the survey.” For instance, she said she would have hoped to see more than 25 percent of presidents leading discussions of consolidating programs or operations with other colleges. “Cooperation and collaboration among institutions is difficult,” Lapovsky acknowledged, because it is “time-consuming and requires great trust among the players.”

But higher education is not going to address concerns about its costs and prices unless “the industry becomes more efficient,” and consolidations among public institutions and greater collaboration among colleges of all types are potential drivers in that direction, she said.

Whittaker said he too was struck by the fact that some presidents seemed to feel less compulsion to make (or sustain) significant changes as their financial situations appear to improve. He found it unsurprising that the institutions least inclined to stick with COVID-era changes that expanded student access (more online offerings, remote operations, less dependence on standardized tests) were public doctoral universities and private four-year colleges with selective admissions who see their enrollments and finances rebounding.

“So many of the COVID-driven changes allowed higher education to serve more people than it’s currently designed to serve, and the willingness to retain those changes probably depends on who [the presidents] see as their students,” Whittaker said. “Institutions that are sensing a more permanent drop-off in students, you’re starting to see them adopt some of these practices longer term, as a way to survive as institutions. Where if you typically served traditional students and you’re seeing those students return, it’s easier to forget the learnings from COVID.”

The Mental Health Landscape

No issue is dominating presidents’ list of worries more than student mental health.

The survey asked presidents to assess their level of awareness about the mental health state of various campus constituents. Unsurprisingly, they reported having the greatest awareness of the situation of undergraduate students, followed by faculty and staff members, with graduate students trailing. (The graduate student proportion is higher when responses from community college presidents are excluded.)

Presidents consider their institutions to be better positioned to meet the mental health demands of students than of employees. They are twice as likely (22 percent versus roughly 10 percent) to strongly agree that their institution “has the capacity to meet the mental health needs” of undergraduates as opposed to faculty and staff members. But over all, a maximum of two-thirds of presidents agree that they can meet the needs of any of those groups. (Presidents of private nonprofit colleges were about 10 percentage points likelier to believe they could meet the needs of undergraduate students—71 percent to 62 percent for public college and university leaders.)

Those who agreed that their institution has the capacity to meet the mental health needs of undergraduate students or other stakeholders were most likely to say that was so because they had increased the budget for mental health–related services (71 percent), invested in telehealth services (70 percent) or increased the availability of appointments with mental health services staff (70 percent).

And when asked why they believed demand for mental health services had risen among students, their top reason—above students’ struggles with balancing economic and familial duties with academics (62 percent) and pre-existing mental health conditions (54 percent)—was “declining student resilience due to the prolonged nature of the pandemic” (76 percent).

Nance Roy, chief clinical officer of the Jed Foundation, which works to protect students’ emotional health and prevent suicide, said college leaders might be more attuned to mental health issues among undergraduates because of the responsibility they feel due to their age and because of a certain group that advocates for them. “Presidents tend to hear a fair bit from parents,” she said.

Yet graduate students on average have more complex lives and more familial responsibilities, Roy said, “so they face a double whammy—more challenges, but they’re not top of mind for administrators.”

Roy said she was heartened that so many presidents were acknowledging the need to better meet the mental health needs of their campuses, but she advised them to think beyond expanding the number of counselors and focus more on a “public health approach” to mental health.

“We should be saving our counseling center folks for those students who really need clinical care,” she said, “and encouraging a culture of care in which everybody from the professors to the groundskeepers has the tools to identify those who need a lot of help and support those who might just be having a bad day.”

Campus Race Relations

A year ago, in the wake of murders of George Floyd and other Black Americans that spurred months of unrest over racial injustice, 63 percent of college presidents rated race relations on their campuses as either excellent (10 percent) or good. That drew some ridicule from national experts on race in higher education, especially because those same presidents assessed the state of campus race relations nationally very differently: 81 percent deemed campus race relations elsewhere to be either fair (66 percent) or poor.

As much as presidents’ relatively rosy assessment of their own campus environment at that time may have seemed tone-deaf, the fact that only 63 percent of presidents rated race relations as good or excellent was actually a steep decline from before the summer of racial unrest; in 2020, 77 percent of college leaders in Inside Higher Ed’s survey that year (which was conducted by Gallup, not Hanover Research) assessed their campus that way.

Fast-forward to now. If presidents seemed slightly more inclined to see their faults within months of the Black Lives Matter tumult, that self-awareness appears to have faded. Asked that same question for this year’s survey, 73 percent of presidents characterized race relations on their campuses as either excellent (10 percent) or good.

That compares to 29 percent who describe campus race relations nationally to be either excellent or good (two presidents out of 375 deemed them excellent), while 64 percent said they were fair and 7 percent poor.

That disconnect consistently troubles and confounds experts on race in higher education.

“In the first few years, this pair of Inside Higher Ed survey responses surprised me,” Shaun R. Harper, Clifford and Betty Allen Chair in Urban Leadership and founder and executive director of the University of Southern California’s Race and Equity Center, said in an email message.

“But at this point, the consistent executive cluelessness about racial realities on campuses year after year after year frustrates me. It is irresponsible.” Students and staff of color would almost certainly answer the questions differently from presidents, Harper said. “These survey responses convince me that presidents consult far too little with people of color on racial topics.”

With the Supreme Court poised to hear a challenge to the consideration of race in admissions at Harvard University and the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, the survey sought the presidents’ views on how their campuses would be affected if—as many legal experts anticipate—the universities lose.

On balance, most presidents play down the potential impact at their institution; only 8 and 7 percent, respectively, agree that their institution would have to “significantly adjust” its financial aid and admissions policies, and just one in seven agree that a ruling curtailing affirmative action would increase racial unrest or worsen race relations on their campus.

Harper strongly disagreed. “A policy that makes Black and Latinx students and employees even more underrepresented than they already are is guaranteed to weaken their sense of belonging,” he said. “This will inevitably exacerbate racial tensions between them and their white counterparts.”

Lukewarm on the New Administration

College leaders aren’t thrilled with what the Biden administration has accomplished so far, and they are skeptical about what it can get done.

About three in five presidents say the administration’s policies have had a generally positive effect on their institution, with public college leaders (69 percent) significantly likelier than their private college counterparts (51 percent) to agree. Far fewer campus leaders, 43 percent, are either completely (5 percent) or somewhat satisfied with what the president accomplished in higher education in his first year in office, with a majority of leaders of nonresearch public and community colleges agreeing.

And nearly half of presidents say they are “not at all confident” that the administration will be able to deliver on the president’s higher ed–related promises at all, given the divided political environment. Just 3 percent describe themselves as extremely or very confident.

Image of Higher Education

Presidents are increasingly worried about Republican critiques of higher education, most of which they dispute. But some they increasingly concede.

In its 2020 survey, Inside Higher Ed asked presidents a set of questions about Republican doubts regarding their institutions. Last year’s survey focused mostly on COVID-related issues and hence didn’t address these topics. Returning to them this year finds significant changes from two years ago.

Presidents are significantly more concerned about the impact of Republican critiques of higher education. And while most still challenge assertions that their campuses are inhospitable to those with conservative views, significantly more presidents concede that some criticisms are fair.

Other Highlights

The survey examined several other timely or lingering issues in higher education. Among other findings (which can be explored in more depth in the survey report):

- Slightly more than half of respondents say that their institutions do not require students or employees to be vaccinated. Presidents of private nonprofit colleges (44 percent) are likelier than their public college counterparts (29 percent) to report that all employees and students are required to be vaccinated. And more respondents from public institutions (58 percent) report that neither students nor employees are currently required to be vaccinated than is true for their private nonprofit peers (46 percent).

- Nearly two-thirds of respondents say that fewer than a quarter of their students had contracted COVID-19 at the time of the survey. About a quarter of presidents estimate that by fall 2022, more than half of their student population will have contracted COVID-19.

- A majority of presidents (57 percent) agree that faculty members on their campuses “understand the challenges confronting my institution and our need to adapt.” That’s the highest level since Inside Higher Ed began asking that question a decade ago, but it is still significantly lower than how presidents rate the understanding of fellow administrators (97 percent) and trustees (81 percent).

- Fewer than half of campus leaders (45 percent) say that their institution “needs a shared governance process that allows for speedier decision making than we currently have.” That figure was 52 percent a year ago.