Free Download

College and university chief business officers increasingly agree higher education is in a financial crisis, yet many are divided over the role a key constituency on campus should play as institutions grapple with budget issues: their faculty members.

Those are major findings in Inside Higher Ed’s 2016 Survey of College and University Business Officers, the sixth such study. The survey, conducted by Gallup, drew responses from chief business officials at 386 public and private institutions among the more than 2,700 administrators invited to participate. A copy of the survey report can be downloaded here.

A headline result is a steep rise in the portion of business officers agreeing with the idea that higher education is in the middle of a financial crisis. Nearly two-thirds of those surveyed, 63 percent, said they felt media reports suggesting a financial crisis accurately reflect the general higher education landscape. Last year, just 56 percent of respondents agreed.

Chief business officers at public institutions were more likely than their private college peers to see a crisis, with 70 percent agreeing with media reports. Still, a majority of business officers at private nonprofit institutions, 60 percent, agreed there is a crisis.

Business officers were more confident in finances at their own colleges and universities, however.

This year, 64 percent of chief business officers strongly agreed or agreed that their institutions will be financially sustainable over the next five years -- the same proportion as in last year’s survey.

Confidence slipped when the timeline was extended to 10 years, with 54 percent saying they were confident in their institutions’ financial stability over that time frame. But the 54 percent mark was up sharply from 2015, when just 42 percent expressed confidence over 10 years.

Percentage of Business Officers Expressing Confidence

in Institutions' Financial Stability Over a Decade, 2014 to 2016

| Institutions | 2016 | 2015 | 2014 |

| All | 54% | 42% | 40% |

| Public | 46% | 44% | 41% |

| 59% | 54% | 37% |

| 42% | 37% | 36% |

| 45% | 45% | 45% |

| Private Nonprofit | 59% | 42% | 39% |

| 66% | 40% | 36% |

| 54% | 41% | 39% |

Chief business officers appear to be recognizing the financial challenges faced by many colleges and universities across higher education, experts said. At the same time, they appear to believe they’re positioning their own institutions for the future.

There has been plenty of bad news to catch business officers’ attention, said Andrew Laws, managing director at Huron Consulting Group, who focuses on college and university finances and business practices.

About the Survey

Inside Higher Ed’s 2016 Survey of College and University Business Officers was conducted in conjunction with researchers from Gallup. Inside Higher Ed regularly surveys key higher ed professionals on a range of topics.

On Thursday, Aug. 18, at 2 p.m. EDT, Inside Higher Ed editors will analyze the survey's findings and answer readers' questions in a free webinar. To register, please click here.

The Inside Higher Ed survey of business officers was made possible in part by advertising from AGB Institutional Strategies, Axiom, Jenzabar, Oracle and Workday.

“It’s become more tangible in the last 12 months,” he said. “There haven’t been stories of stress. It’s been stories of closings. You’ve seen the continuation of more credit rating downgrades. You’ve seen growth in the Department of Education’s list of heightened-cash-monitoring institutions.”

Business officers may be more bullish on their own institutions because they feel they’ve taken steps to secure themselves against financial threats. Those in some parts of the country, like California, with its increased state higher education funding, may see themselves in better financial situations. Or some may be ignoring their own problems while feeling relieved that they haven’t run into immediate crises, Laws said.

But several experts said the survey indicates business offices are not broadly engaged in the deep, strategic work necessary to deal with the broad financial crisis they report. They see business officers as trying to buy their way out of the situation instead of taking a deep look at costs.

“Reading into this, I don't see a strong thread of evidence that the deeper work on restructuring this [enterprise] is really underway,” said Jane Wellman, senior adviser to the College Futures Foundation. “The problem with higher ed finance is that there will be a time when the money's going to dry up again. Student enrollments are going to keep stabilizing or declining, full-pay [students] will go down.

“The conditions that would allow one to be optimistic long term aren't there,” Wellman said.

Future Strategies

Experts' concerns over strategies started with business officers' perceived unwillingness to shutter programs at their own institutions. Those concerns continued when they saw many business officers hoping to improve finances by boosting enrollment.

A large majority of chief business officers said most colleges are too hesitant to shut down academic programs, 90 percent. The majority shrank significantly when business officers were asked about their own institutions, though -- just 68 percent said their own college was too hesitant to shut down academic programs.

Another large majority, 85 percent, said colleges need to be more willing to experiment with new kinds of academic and nonacademic offerings in order to build new revenue streams.

A hesitancy to close existing programs combined with interest in starting new ones is not a recipe for sustainability, said Laws, of Huron Consulting Group.

“I think what you should be looking at is the mix of academic programs and how you create a sustainable academic portfolio,” he said. “You’ve got to have enough of those kinds of market-relevant, profitable academic programs that you can subsidize these high-cost, mission-critical programs. I think there’s still a hesitancy to do that.”

The survey gave chief business officers a list of 18 potential ways to improve their institutions’ financial situation. Business officers proved most receptive to trying to increase enrollment.

For the 2016-17 academic year, 87 percent of chief business officers said they strongly agreed or agreed their institutions would implement strategies to increase overall enrollment. That outpaced launching new revenue-generating academic programs at 71 percent, exploring collaboration opportunities for academic programs with other institutions at 65 percent and eliminating underperforming academic programs at 43 percent.

Those numbers show institutions are not looking to the future, said Wellman of the College Futures Foundation.

"If they were really doing the anticipatory stuff, we would see higher numbers on academic program restructuring,” she said. “They haven't made this a routine part of the way they do business. It's still something you do when you have to.”

Other strategies a significant portion of business officers said they would pursue to improve their finances included enrolling more full-pay students at 43 percent, exploring collaboration opportunities for administrative services with other institutions at 39 percent, lowering the tuition discount rate at 36 percent and reducing administrative positions at 35 percent. Additional strategies were increasing teaching loads for full-time faculty at 32 percent, shifting more undergraduate teaching to part-time or nontenured faculty at 31 percent, shifting from classroom-based to web-based instruction at 30 percent and outsourcing more administrative services at 26 percent.

The relative lack of interest in increasing teaching loads surprised Art Hauptman, an independent public policy consultant who specializes in higher education finance.

“I understand you have limited control over your faculty,” he said. “The faculty wants to teach fewer courses and do more research. That’s sort of the basic tension in the system, which [business officers are] in the middle of. But why, if you really were in trouble five or 10 years down the road, wouldn’t you say, ‘Here’s the situation and we need you to teach another course a semester’ rather than cut people?”

Just 11 percent of chief business officers agreed they would pursue cutting spending for intercollegiate athletic programs. That was below promoting early retirement for faculty at 27 percent, shifting more undergraduate teaching to senior faculty at 22 percent, promoting early retirement for administrators and staff at 17 percent, and revising tenure policies at 13 percent. But it was above outsourcing more academic programs at 5 percent.

Some experts hadn’t anticipated such a heavy emphasis on boosting enrollment.

“I was surprised that so many CBOs named enrollment growth as the remedy of choice for financial difficulties,” said Stefano Falconi, managing director of the Berkeley Research Group LLC in an email. “This is a very traditional response, but not very feasible in those regions where demographics are not favorable. It is also not very meaningful in the absence of clearly defined discount-rate goals.”

Colleges and universities will need to focus on enrolling a new type of student if they hope to grow in the future, said Gary Rhoades, a professor and the director for the study of higher education at the University of Arizona. Rhoades is also a member of the National Association of College and University Business Officers’ economic models national task force, he said.

Colleges and universities are currently pursuing a shrinking demographic of wealthy, white students, Rhoades said. He suggested more efforts to increase enrollments by tapping into other, growing demographics, like first-generation college students, students of color, lower-income students and immigrants.

Some institutions can chase wealthy and out-of-state students that pay higher net tuition, Rhoades said. But many others will end up spending large amounts of money to woo those students, only to lose out to better-known competitors or fail to retain those students after a few semesters.

“You’re chasing money at the cost of not only diversity, but you’re doing it at the cost of quality,” he said. “It’s not even sustainable.”

Faculty Role

Chief business officers varied more widely in their opinions when it came to the question of involving faculty members in budgeting. Just 33 percent of business officers agreed that faculty members have been supportive of efforts to address budget problems at their institutions. The portion who said faculty members had not been supportive was only slightly different, 27 percent. That left 40 percent neutral on the question.

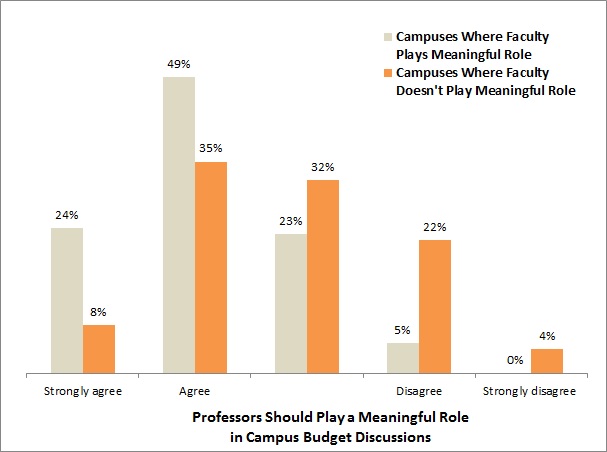

Meanwhile, 43 percent of chief business officers said faculty members played a meaningful role in collegewide budget decisions at their institutions. The remaining majority, 57 percent, said the faculty did not play a meaningful role in such decisions.

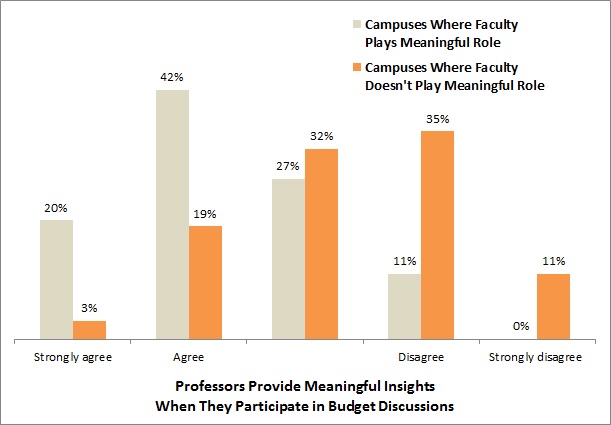

That question proved to be a fault line between diverging attitudes toward faculty involvement in budget discussions. Business officers who said faculty members played a meaningful role in budget discussions on their campuses were much more likely to value faculty members' contributions and to say that faculty members understood institutionwide financial challenges.

They were also more likely to say faculty members should be involved in budget discussions. Among chief business officers who said faculty members play a meaningful role in budget discussions, 73 percent agreed faculty members actually should play such a role. Just 43 percent of chief business officers who said faculty members do not play a meaningful role in budget talks felt the same way.

The gap was similar on the question of how much insight faculty members provide in budget discussions. Among chief business officers who said faculty play a meaningful role in budget discussions at their institutions, 62 percent said faculty members provided valuable insights in the discussions. Only 22 percent felt the same way at institutions where faculty members did not play a meaningful role in budget talks.

Divisions continued on the issue of whether faculty members understand the financial challenges an institution faces when they participate in collegewide budget discussions. Among chief business officers who said faculty play a meaningful role in budget discussions, 41 percent agreed faculty members understood financial challenges. Just 15 percent agreed among those who felt faculty did not play a meaningful role in budget discussions.

Those attitudes had some calling for business officers to listen to the faculty more. Professors can provide important information on a range of issues, including whether shutting down programs is a good idea, said John Barnshaw, senior program officer and senior higher education researcher at the American Association of University Professors, who previously directed the Delaware Cost Study. The insight faculty provide can be important when hard decisions have to be made, he said.

For instance, an administrator might push to close an academic program because it generates few degrees. But those programs might host classes that are requirements for other majors, so shutting it down can have unintended and expensive consequences, Barnshaw said. He added that faculty members can have ideas that would reduce costs or prove helpful to institutions’ bottom lines.

“That is a tremendous opportunity for education of business officers,” Barnshaw said. “Faculty actually know a lot about their subject areas, and they have a lot of connections in the communities in which they work.”

Others cautioned that additional faculty involvement can be a challenge.

“There often aren’t processes that bring [faculty members] into a meaningful role in collegewide budget decisions,” said Donald Heller, provost and vice president of academic affairs at the University of San Francisco and a researcher who studies higher education finance. “You can’t separate financial issues from academic issues at most institutions, but the fact of the matter is relatively few faculty members have an interest in the broader financial issues at an institution.”

Ultimately, the question becomes how much faculty are involved and in which issues, Heller said.

“It’s always a balancing act,” Heller said. “For example, if you’re looking at the issue of faculty compensation and the impact that has on your budget, then of course faculty are going to be much more involved.”

Over all, 54 percent of chief business officers said faculty members should play a meaningful rule in collegewide budget decisions, and 40 percent said faculty members provide valuable insight during budget discussions. Also over all, 39 percent said faculty approval should be required when colleges consider new revenue-producing programs, and 27 percent said faculty members understand the financial challenges institutions face when they take part in collegewide budget discussions.

Faculty involvement is an important point when considered in light of other survey findings on performance and program evaluation. A large portion of chief business officers signaled their institutions lack information needed to make decisions. Just 51 percent said they had the information needed to make informed decisions about which academic programs should be eliminated or enhanced, and 49 percent said they had enough information to make informed decisions about the efficacy of specific academic programs and majors.

Additionally, 44 percent said they had enough information to make informed decisions about the performance of individual faculty members. Only 40 percent said they had enough information to make informed decisions about the performance of academic technology, 39 percent said they had the information to make informed decisions about administrative technology performance and 34 percent said they had enough information to make informed decisions about each administrative unit on campus.

Faculty members could provide information in many of those cases, Barnshaw said.

“If an institution is going to move forward, it’s important that budget officers reach out to the faculty in real, cogent ways,” he said. “I often hear from budget officers that faculty have no idea. Those budget officers can educate, and faculty members can probably educate budget officers.”

Debt Levels, and Other Findings

Other results of the survey include the following:

- Fifty-seven percent of business officers agreed or strongly agreed that new spending at their institution in the years ahead will come from reallocated dollars rather than new revenue. That was especially true of public university CBOs, a full two-thirds (67 percent) of whom responded that way, and 75 percent of those at public master's and baccalaureate institutions.

- A question on trustee understanding of campus finances revealed a major public-private divide. While 80 percent of business officers at private nonprofit colleges agreed that board members at their institutions "are aware of and understand the financial challenges confronting my institution," just 64 percent of those at public institutions agreed. Business officers at public doctoral institutions had the least favorable view of trustees: just 45 percent of them said board members understand their institutions' finances.

- Almost three-quarters of business officers believe their institution has the appropriate amount of debt. Seventy-two percent of those surveyed gave that answer, while 14 percent said they believed their college or university had too much debt and 14 percent thought it should take on more. Only 62 percent of CBOs at private baccalaureate institutions said their college had the appropriate amount of debt -- but 20 percent said they had too much, and 18 percent thought it should absorb more. A majority of business officers (52 percent) disagreed with the view that their institution had underutilized debt as a financing strategy.

- Nearly half of CBOs (49%) say their institutions cannot make additional and significant spending cuts without hurting quality.

- 4 in 10 business officers say their institution’s tuition discount rate is unsustainable; figure is 50 percent at private colleges, 28 percent at publics, and 60 percent at private baccalaureate colleges.

- CBOs overwhelmingly agree that financial issues, not ethical or political ones, should drive decisions on investing endowment funds.

- Acceptance of the federal financial responsibility score appears to be on the rise. Sixty percent of business officers said they included the federal score among the menu of indicators their institution uses to gauge its financial health. In the 2015 Inside Higher Ed survey, that number was 52 percent.

Doug Lederman contributed to this article.