You have /5 articles left.

Sign up for a free account or log in.

Professors weighed in on their advice for tackling ChatGPT roughly one year after it launched to the public.

Getty Images

Soon after OpenAI launched ChatGPT—a generative artificial intelligence chat bot with the potential to seemingly answer any question under the sun—academia panicked.

In the following year, ChatGPT drew comparisons to the calculator, Wikipedia and the cellphone, illustrating the initial alarm and eventual symbiotic, if begrudging, relationship with higher education.

Since then, adoption of ChatGPT and other AI tools has surged. Reports show more than half of college students using generative AI, while faculty members are, slowly but surely, upping their familiarity.

Two months after ChatGPT’s launch, Inside Higher Ed consulted with 11 academics on navigating this new terrain. A year ago, we shared their advice, advocating for a balance of action, patience, optimism and caution. Now we revisit most of them to see if their advice still holds true, what has evolved and what faculty members can do in 2024.

Answers below have been edited for length and brevity.

View AI as a Tool, Not an Overhaul

Paul Fyfe, associate professor of English at North Carolina State University

A year ago I talked a lot about expansive gray areas, and I think we’re still there in a lot of ways. There are some things that have come into focus in the year—ChatGPT elevated generative AI into public and academic consciousness—but by and large we’re still very much seeing norms, rules and regulations in development and still needing a coherent institutional approach to cultivating AI literacy.

My [updated] advice is [to] try to understand it as far as you need to and approach it like a tool for specific things rather than as some computational mastermind or human replacement.

I think it’s been heartening to see there has been at least some development in generative AI … that the discourse around AI has moved helpfully away from this free-floating, “Is it conscious?” to “OK, it’s a tool with problems and possibilities. How can it be used?”

I’m getting a sense some uses of it are getting normalized, including for brainstorming for research assistance, or feedback of student assignments and work. What’s also interesting is many students don’t assume AI will be correct. Many students have been discovering what normal AI practice looks like through their own experimentation and sharing with each other.

Don’t Overestimate, or Underestimate, the Effects of AI

Steve Johnson, senior vice president for innovation, National University

I stand by what I said in 2023: from what I observed, people who did try big things learned big things this past year.

A year later, my advice is that we still need to be considering five to 10 years ahead and really imagine what that could and should be like. It’s Amara’s law: we overestimate the effect of technology in the short term and underestimate the effects in the long run, because of things you’ve read of “This is a hype cycle.”

But if you’re not thinking, “What is writing going to be like in five to 10 years when I compose in a different way,” or [making] different writing choices because you’re writing with an AI buddy … If we’re not thinking of those things, a lot of people get blindsided, especially younger students. They wouldn’t be able to address what they’re learning and how they learn.

Analyzing Is More Important Than Ever

Johann Neem, professor of history at Western Washington University

[In 2023] my advice focus was on “Can ChatGPT write student papers?” As I thought about it, I still stand by what I said, which is “We don’t want to let computers think for us,” but I would emphasize now [that] the reading skills we cultivate in the humanities are essential … in a society where we are bombarded with machine-generated text and images.

There’s a need as readers and people who engage with the humanities to have the skills to go deep in something and understand when there’s real facts and when it’s made up or seems off.

There was this initial reaction of “Oh my god, they’re going to take our jobs,” but these traditional reading and seminar skills are more vital than ever, so we need to refocus our attention on that, in what we teach and what students learn.

Keep Experimenting While Being Mindful

Robert Cummings, executive director of academic innovation at the University of Mississippi

I see more students and faculty have realistic expectations of generative AI outputs and see where AI misses the mark and hallucinates. Now both student and faculty are a little more circumspect about it—on its use for the student side and on the faculty side, the potential damage it may do.

I had a recent publication, which says engage with it, give students a chance to experiment with it, give them a chance to evaluate it—but then give them the chance to reflect on it. That’s the key part, because then they can assess whether the tool is useful for them. And that’s what they’ll be asked to do in their workplace—they’ll have to figure out which are good and useful [tools] and the ones not used in an effective way.

Embracing—and Critiquing—AI Can Co-Exist

Anna Mills, English instructor at Cañada College

I definitely stand by my advice in 2023, although I would frame it a bit differently. I was a little on the side of warning people against the AI hype and seeing myself as a critic, but I’ve moved more toward the position of teaching “How do I interact with the system and improve on it?” That’s where students have to be in the workplace. And it’s also where you learn to have perspectives and think of where we might want to limit how we use them.

It’s become more relevant than ever that we need to teach students to understand and critique AI at the same time.”

—Anna Mills

We don’t have to become huge experts and let AI take over classes to introduce AI literacy; I’ve been offering five-minute microlessons people can integrate, showing a few images revealing AI bias. Specific, simple examples can stick in people’s memories and aren’t difficult to teach. We don’t have to revamp the whole curriculum.

Pay Attention to AI Beyond ChatGPT

Ted Underwood, professor of information sciences and English at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign

When we spoke last year, I hadn’t yet done much research with large language models. It’s clearer than ever to me that, in spite of their limits, these are going to be valuable tools for summarizing, annotating and perhaps even generalizing about large collections of documents and images. I do think that doctoral students in many fields should be learning how generative models work, what their limits are and how to automate the query process.

The other new thing that I would draw scholars’ attention to is voice interaction. The quality with transcription and generated voice is getting impressive, and when this rolls out to a wide audience (say, if Apple makes it part of iOS), I think it will have a bigger impact on public perception of AI than we have seen so far. Academics may care primarily about the cogency of a model’s reasoning process, but there are many users who care more about intonation and expressiveness. The new models sound smart, even when they aren’t, and (for good or ill) that is likely to make a difference.

Be Proactive

Marc Watkins, director of the AI Summer Institute for Teachers of Writing at the University of Mississippi

The reactionary period is over. It’s time for institutions to look at generative AI beyond ChatGPT and take proactive measures. We cannot expect the acceleration in deployments of new AI tools to slow down, nor can we hope for a technological solution in the form of unreliable AI detection to curb its impact. We need to focus instead on developing a sustainable AI literacy for all stakeholders.

Faculty Need to Catch Up to Student Levels of Adoption

Stephen Monroe, assistant dean of the College of Liberal Arts at the University of Mississippi

The average faculty member has a lower AI literacy than the average student. This is not good, and we must reverse the relationship.”

—Stephen Monroe

Provosts and deans should route funds now to support local faculty development efforts. The next two or three years will be critical. Every faculty member on every campus needs to get up to speed.

I’ll also say that part of this work must be done in person. Online resources and Zoom sessions can be helpful, but there is an emotional aspect to this challenge. Faculty will need local, face-to-face guidance from trustworthy colleagues. They’ll also need community and ample time to grapple, to experiment, to think deeply about the implications for students in their courses.

This kind of faculty development is happening here and there, but we need to scale more quickly than usual. Those of us in education did not ask for this disruption, but we must deal with it, and we are equipped to do so. Our students will need our guidance to learn ethical and effective use of generative AI in their disciplines and professions. I’m optimistic in this moment, but cautiously so.

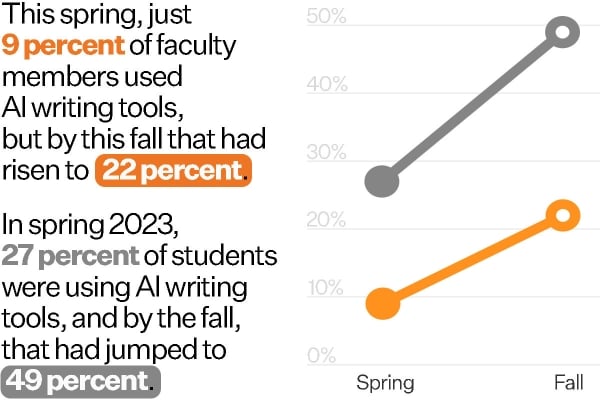

According to a Tyton Partners study, students have always outpaced faculty in using AI, but usage among faculty and students are increasing.

Source/Tyton Partners, Justin Morrison

Change Takes Time; Be Patient

Michael Mindzak, assistant professor in the Department of Educational Studies at Brock University in Canada

I think in the year ahead we still have to look at ChatGPT—it landed on us and it felt like a revolution in a sense of “Everything is going to change.” But with things like this, it’s more of a process. It takes time to see implications of that, how we can respond, what changes and what doesn’t.

A good example is cellphones in the classroom: 20 years ago, cellphones came in class, and we still don’t have an answer of “Should they be banned; should there be a place for them?” We’re no closer 20 years later, and with AI, it’ll be similar. You have to look at it over time and see what changes year over year.

Communication Across Institutions Is Key

Mina Lee, incoming professor in computer science at the University of Chicago

I believe it’s still important for each teacher, student and administrator to feel the responsibility and be able to participate in the decision-making, responsible use and usage report in the pipeline. However, with the fast-changing development of AI (e.g., several new large language models are released each month, and some of the closed models are consistently updated behind the scenes), it is becoming incredibly difficult for individuals to keep track of recent advances and changes to be able to make informed judgment.

Instead of delegating responsibilities, maybe they should be shared across teachers, students and the administration (institutional and governmental). For instance, although a teacher of a class might be more well positioned to assess the overall quality of an AI tool than students, it might be the students in the class who will exhaustively use the tool and discover intrinsic issues within the tool (e.g., cultural bias that was not apparent to the teacher). In this sense, being able to communicate the findings and issues across stakeholders and keeping each other accountable becomes more important than ever.