You have /5 articles left.

Sign up for a free account or log in.

Coursera is the latest to launch a tool for detecting the use of AI in student work.

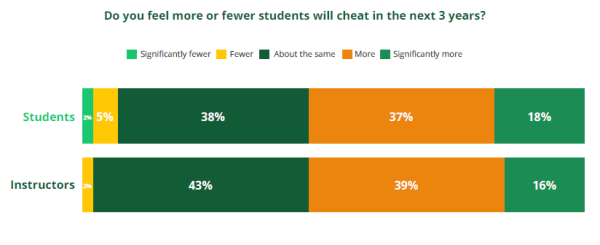

While instructors and students see the potential of generative artificial intelligence—which can be used for everything from creating rubrics to getting study-guide help—they also see the potential for a rise in cheating aided by the technology.

According to a report released today and shared first with Inside Higher Ed by publishing firm Wiley, most instructors (68 percent) believe generative AI will have a negative or “significantly” negative impact on academic integrity.

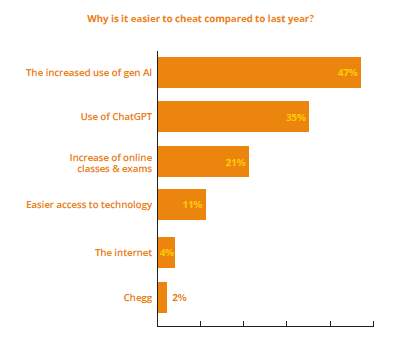

While faculty concerns about the use of AI to cheat are nothing new, the study also polled more than 2,000 students—who agreed that generative AI will boost cheating potential. Nearly half of them (47 percent) said it is easier to cheat than it was last year due to the increased use of generative AI, with 35 percent pointing toward ChatGPT specifically as a reason.

The numbers were not particularly surprising to Lyssa Vanderbeek, vice president of courseware at Wiley. “Academic integrity and cheating have been around forever,” she said. “It’s not surprising that it’s increased because of the fast evolution of these generative AI tools and their wide availability, but it’s not a new challenge; it’s been around for a long time.”

It’s important to note that the survey—which polled 850 instructors along with the 2,000-plus students—did not specifically define “cheating,” which some could view as fact-checking an assignment while others think it would only include writing an entire paper through ChatGPT.

Vanderbeek said she has seen a more open dialogue about cheating between professors and students in the classroom.

A Wiley survey shows students and faculty both expect to see cheating increase in the next three years, aided by generative AI.

Wiley

“One thing we’ve noticed with instructors is discussing in the classroom what cheating is and normalizing getting help—and looking at productive ways to get help,” she said, “versus it being, ‘Where do you cross the line with cheating?’”

When OpenAI’s ChatGPT first hit the scene in November 2022, it immediately drew concerns from academics that believed it could be used for cheating. In an Inside Higher Ed survey released earlier this year, nearly half of university provosts said they are concerned about generative AI’s threat to academic integrity, with another 26 percent stating they are “very” or “extremely” concerned.

Many institutions were quick to ban the tools when they first launched but have loosened the restrictions as the technology—and attitudes toward it—has evolved over the past 18 months.

Technology and academic experts have often drawn comparisons to similar fears that emerged when Wikipedia was first released in 2001, or in the 1970s when calculators were first widely introduced into classrooms.

In the Wiley survey, a majority of professors (56 percent) said they did not think AI had an impact on cheating over the last year, but most (68 percent) did think it would have a negative impact on academic integrity in the next three years.

On the flip side, when asked what made cheating more difficult, more than half (56 percent) of students said it was harder to cheat than last year due an uptick in in-person classes and stricter rules and proctoring. Proctoring saw an uptick during the pandemic when courses became remote, and many institutions have kept the practice as classes shifted back to face-to-face.

Students believe it is easier to cheat in class compared to last year, largely due to generative AI and ChatGPT.

Wiley

Students who stated a strong dislike for generative AI cited cheating as the top reason, with 33 percent stating it made it easier to cheat. Only 14 percent of faculty cited the potential for cheating as a reason for disliking the technology, with their top reasoning (37 percent) being that the technology has a negative impact on critical thinking.

Vanderbeek said she was surprised at the number of students who simply did not trust AI tools—with 36 percent citing that as a reason they don’t use them. Slightly more (37 percent) said they did not use the tools due to concerns their instructor would think they were cheating if they used AI.

And as reported in previous surveys, including Inside Higher Ed’s 2024 provosts’ survey, student use of generative AI greatly outpaced faculty use—45 percent of students used AI in their classes in the past year, while only 15 percent of instructors said the same.

Vanderbeek said there are three main approaches institutions can take when looking at keeping academic integrity intact: creating incentives throughout the work process, like giving credit for starting early; introducing randomization on exams so it is harder to find answers online; and providing tools to instructors to identify “suspicious” behavior, like showing copied-and-pasted content or content submitted from overseas IP addresses.

“The takeaway is that there is still a lot to learn,” Vanderbeek said. “We see it as an opportunity: There are probably ways generative AI can help instructors provide learning experiences that they just can’t right now.”