You have /5 articles left.

Sign up for a free account or log in.

Professors have found students are motivated by receiving rewards you’d typically see in video games, including badges and in-game currency.

Yan Shi’s computer science course at the University of Wisconsin at Platteville isn’t exactly typical.

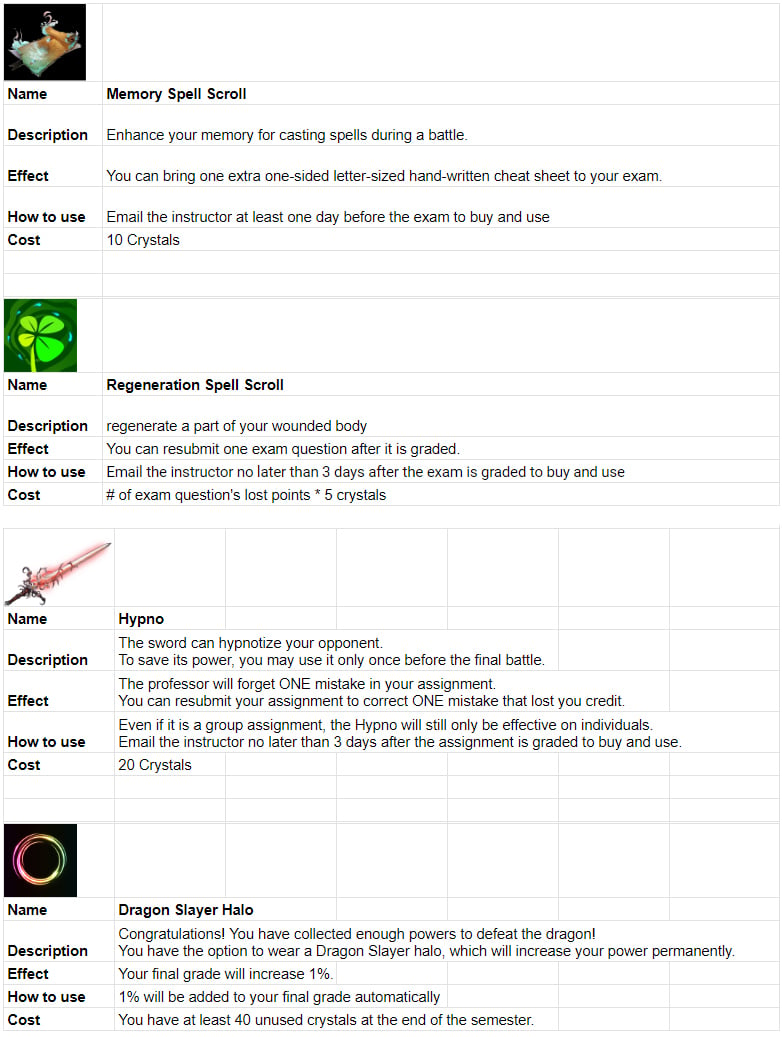

Not simply a professor, Shi is a “king of the kingdom,” and her Intro to Computer Science class is informally dubbed the “dragon slayer game.” Students are “warriors” with weekly quests to acquire spells and weapons—and also knowledge.

“In the past, it’s, ‘It would be really beneficial for you to try this [extra work],’ but that’s not enough of a push; students will hear me and forget about it after class,” Shi said. “I was wondering if there was a way to motivate students to learn a little beyond the required material.”

Many have seen gamelike exercises in K-12 classrooms, but expectations for those kinds of pedagogies typically stop at the gates of higher education.

But Shi and other professors across the country are beginning to integrate gaming into their courses, even overhauling them to include elements from video games such as leaderboards and earned badges.

“A lot of feedback is ‘Games are not serious,’” said Michael Brown, an associate professor of education at Iowa State University. “Part of the reason people like to play games is that they’re fun; if you make learning experiences transformative but also fun, they’re more engaging.”

Games in the Classroom

Gamification goes beyond playing video games on educational topics—it includes incorporating gamelike assets into learning, such as badges, leaderboards and tokens.

Shi turned her course into a game in fall 2022, sending students on different “quests” to learn new information beyond the standard course material. For example, one quest was heading to the annual career fair to talk to software companies. In the prompt, it was “finding the magic store” that “sells weapons,” which have clues the prospective employers can give.

Yan Shi, University of Wisconsin Platteville

It is one of seven quests Shi gave out as additional work, which garnered a 70 percent participation rate—much higher, she said, than the participation rate for work garnering extra credit points.

Iowa State University’s initiative, Game to Work, brings together an interdisciplinary group of faculty to raise enthusiasm around, and research, the benefits of gamification. One piece of the initiative was “Game Jam,” where students across campus collaborate over a weekend to create a game. The concept is similar to hackathons for coding, and Brown said the university had hoped to get roughly 30 students to sign up. They ended up with 85.

“There is a gaming culture on campus that, even when I was in undergrad, didn’t feel as present,” he said.

After a brief hiatus due to the COVID-19 pandemic, the university relaunched a graduate course dubbed Game-Based Learning for students designing games or learning experiences. Brown is teaching the course this semester.

“I was worried about the class, to be honest—if I don’t get a certain number of grad students, we can’t offer it,” he said. A day later, he began receiving emails asking about a wait-list option. “There’s a lot of enthusiasm around [gamification], and I don’t think it’s just ‘They play games.’ There’s a lot of things games can teach you that are transferable skills, like resilience and thinking strategically.”

Julie Winter launched her education gaming company, Alchemie, in 2013 after seeing an opening in the higher education sector.

“People sometimes hear what I do and automatically put me in the K-12 space,” she said. While Winter was an organic chemistry teacher at a high school, she began playing with gamification in a summer school course intended to prep students for college. “And I thought, ‘I need something more scalable.’”

She first released an app called Mechanisms before launching a web-based game in 2019 for organic and traditional chemistry. The site has roughly six games, all with a focus on accessibility—something that is still relatively untouched in the gaming world.

An Alchemie game that lets users create various cells in an accessible way.

Alchemie

“It was ‘I would love to integrate your stuff, but we have this accessibility hurdle,’” said Joe Engalan, Alchemie’s chief technology officer. Someone who is blind or has low vision, for example, would have a hard time dragging an atom on the screen to create DNA. Alchemie offers an accessibility control panel that describes the current model in text for the player. “We saw the need and that we’re not getting anywhere without addressing that need.”

How It Works

Iowa State’s Brown, after receiving a National Science Foundation grant, built a gamification platform to incentivize students. The platform, which motivated students through badges, also aimed to provide feedback for the students’ chemical engineering candidacy exam.

The platform also has low-stakes rewards to motivate students. For example, if a student logs in to the dashboard 100 times, a dinosaur pops out and walks across the screen.

“I thought it was silly, but they all wanted that dinosaur,” Brown said. “If it’s a way to get students to log in and make a plan for the week, I don’t know if it’s a bad thing to play games.”

Out of the 12,000 students in chemical engineering and introduction to chemistry courses, the ones with access to the dashboard got grades 25 percent higher than those without access, according to Brown.

Brown’s research has found, unlike the popular leaderboard strategy in online games and even workout classes, students are more motivated when they’re competing against themselves instead of their peers.

Peer competition can be particularly detrimental in STEM courses, where some underrepresented students already have disadvantages.

“If your goal is broadening access to STEM, peer comparison is not a great strategy; it’s actually harmful,” Brown said.

Darina Dicheva, a professor of computer science at Winston-Salem State University, has studied gamification extensively, finding it helpful especially for the “middle pack” of students, or those who are not categorized as high or low achievers.

In her research, she also found using multiple gamification elements—like earning virtual currency plus badges—is more beneficial than using a single element.

STEM courses can be particularly helped through gamification, according to Dicheva and Shi, due to the amount of practice needed to nail down STEM-centered concepts.

“When someone says gamification doesn’t work well, it depends on many things,” Dicheva said. “It depends on the instructor, what game elements are chosen in the particular class, the students in the class.”

Future Adoption

Gamification is slowly seeing adoption but has yet to reach the threshold of popular acceptance. Brown said it was seeing a bit of an upward trend before the pandemic, which placed gamification on the back burner.

Adoption also could be slow, the professors said, due to a lack of support within institutions and infrastructure in learning platforms. Platform management sites like Blackboard and Canvas, for example, offer some gamification elements for professors to include, but they have many restrictions and are not customizable.

Dicheva said she sees lower adoption in the U.S. than in Europe, and she attributes that to a lack of administrative support and research about the benefits.

“There’s a lot of interested instructors where they say how nice it sounds, but the support—if they get any at all—is not sufficient,” she said.

Others simply may not know they are engaging in gamification.

“If people find effective ways to use it, it may be one of those things everyone uses and we don’t realize it,” Brown said. “There’s a lot of concern this is just a fad and maybe calling it gamification or putting these things together is the fad, but the pieces that make up the pedagogy are good practices.”