You have /5 articles left.

Sign up for a free account or log in.

Quill.org, a nascent educational technology moving into American classrooms, is described by Ben Schiller of Fast Company this way: “[Student] responses are logged by computers and analyzed for patterns. Algorithms take account of every false word they type, every misplaced comma, every inappropriate conjunction, deepening a sense of where the nation’s kids are succeeding in sentence-construction and where they need extra help.”

“The algorithms substitute for human intervention. Instead of teachers having to correct errors late at night with a red pen, the system does it automatically, suggesting corrections and concepts on its own.”

Feeling compelled to write about Quill.org, I was trotting out my usual critiques of ed tech solutionism combined with trying to correct some pervasive misunderstandings about how writing is best taught and learned, and I simply grew weary at my own effort. I was repeating myself.

The same story pops up weekly, if not daily, bold promises from a tech wunderkind (Quill.org’s founder, Peter Gault is a “wiry and energetic entrepreneur in his mid-20’s”) who is well funded by educational philanthropies in search of an educational magic bullet. I have very little new to say on this front that I haven’t said before.

But I was brought short by the penultimate paragraph in the Fast Company article where Gault describes his initial vision was “a startup that encouraged low-income students to debate social issues and thus improve their critical thinking. But he soon realized many, particularly low-income students, are struggling with the ‘basic building blocks of language,’ and he’d have to start at a more fundamental level.”

Our tech wunderkind first identified a worthy, meaningful goal, but that goal was sacrificed on the altar of “correctness.” If students can’t express themselves according to narrow (and please check out the approved modes of expression the algorithm dictates) proscribed ways, they’re apparently not ready for ideas.

Given what we know about human behavior, motivation, and education, in what world does this make sense?

--

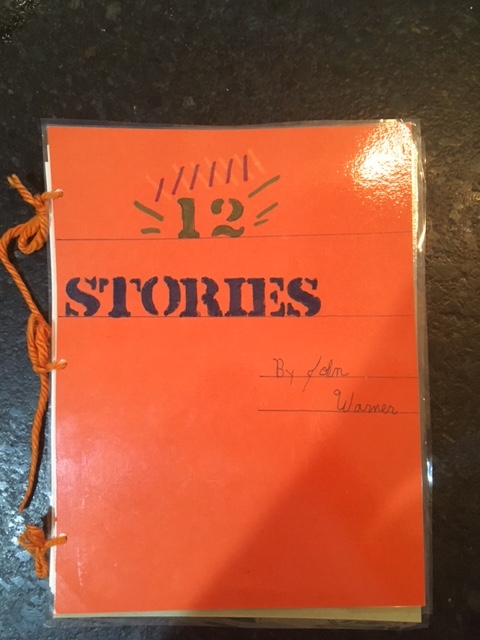

Thankfully, when I was a student, particularly in grade school, I was not subject to an overarching ethos of “correctness.” I know this not only from my memories of my experiences but because for some reason, my mother saved my writing “portfolio” from fifth grade, and for other unknown reasons, it remains in my possession.[1]

Imaginatively titled “12 Stories,” it consists of twelve stories written in varying forms, including “poetry” (“When Joe Got Rid of Flo”), drama (“Future Family Robinson”) and speculative fiction, (“A Dog’s Point of View”).

“A Dog’s Point of View” is written from the perspective of my childhood dog, a sheppard/lab mix named Melvin who was something of a character. For some reason, it starts in verse, a technique which is later abandoned without explanation. The opening lines verbatim, errors intact:

Hi, my name is Melvin.

Everybody says I’m swellvin.

I eat allot napkins, hot dogs and anything with reason.

But I never eat anything out of season.

Mrs. Minch, my fifth grade teacher, did not seem to mind that “swellvin” isn’t a word. She also did not mar my young genius by correcting “allot” with “a lot” or reprimanding me for starting a sentence with a conjunction.

One of the “stories” is an ad for selling my old skateboard. Another is an epistolary diary set in the 1800’s which includes purposeful yellowing of the notebook paper, and even a singe mark (for sure executed by Mrs. Minch) for authenticity’s sake.

I was an accelerated student at a well-resourced school in an affluent Chicago suburb. I had as many advantages as you could name, but this artifact of fifth grade demonstrates that when it came to learning to write, one of the greatest advantages I was allowed, was freedom, including the freedom to make mistakes of “correctness” in pursuit of my own idiosyncratic interests.

The “stories” themselves are riddled with errors. "False" words abound. Some of this is because poor fine motor skills made my handwriting atrocious, but it’s also because I was in fifth grade and if we wait for correctness to come first, we’ll never allow students to wrestle with ideas that are meaningful to them.

Apparently, even in fifth grade, I was interested in education, though I was a burgeoning ed-tech entrepreneur, at least in conception. The apparent prompt for my portfolio piece, “Learn in Your Sleep (and put teachers out of work)” was to create an invention. Mine was the “Capulerari Acidizer Platizski Educationer”[2] (CAPE). I described it as, “a small computer which is programed (sic) with every subject.”[3]

I declared: “With my invention you can fire all the teachers and hire computer programers. (sic once again)

The technology would feed you information while you sleep via “brain waves” which would allow you to complete all of grade school in a single year.

My vision of a future with the CAPE comes in the concluding paragraphs.

“While in the morning you work at a job. You can read books while your asleep. You can hear music while your asleep.

“The average cost of a computer is 5000 dollars which is much less than the cost of an education.”

My ten-year-old logic is not too different from some of what you hear in certain corners of education technology.

I now recognize my school’s willingness to allow me to experiment with words as an important component of my ultimate life as a writer of many different things in many different contexts. I was allowed and encouraged to practice writing in compelling and grade-appropriate ways, including a “celebration” of my work in a portfolio that has survived more than 35 years.

In her study of successful writing academics[4], Helen Sword identified some of the characteristics for writing the writers keep in mind as they work, things like “concision,” “structure,” “voice,” “identity,” “clarity,” “vocabulary,” “agency,” “audience,” and “telling a story.”

When they think about the sentences themselves they consider not grammar, a word we associate with correctness, but “syntax” and “style” the arrangement of words in the expression of an idea.

If this is the work of writers, why shouldn’t writers of every age be encouraged to explore these concepts as they’re writing across many different contexts and for many different audiences?

Correctness has so little to do with the work and ways of writing as writing is being done, it seems counterproductive to emphasize it above all else.

Much is sacrificed on the altar of correctness.[5] Even those who primarily value correctness lament that it is in short supply, even as we’ve orienting towards this particular goal for decades. It also shouldn’t be lost that we require it of students from less privileged backgrounds, while others are granted freedom to explore.

I was allowed to invent a word, “swellvin,” even as I was also learning the “basic building blocks of language.” I believe that freedom to invent goes hand in hand with a desire to learn those basic blocks. I was encouraged to be the strange kid the portfolio reveals.

What a privilege. What if we extended it to all students?

[1] I do not own a single artifact from college, save some Penguin paperbacks from lit classes, but this thing survives.

[2] I have no idea what those words could mean. My guess is I thought they sounded funny.

[3] I’m guessing that I was inspired by the classic Disney film starring Kurt Russell, The Computer Who Wore Tennis Shoes.

[5] I feel like I need to now put in a disclaimer every time I write about this, but for the record, "correct" expression and communication is a vital part of writing and writing instruction. It just isn’t the be-all and end-all and correctness should not be the price of entry for students to work with more compelling material in more compelling ways. When students have something they desperately want to say, they will be motivated to say it well.