You have /5 articles left.

Sign up for a free account or log in.

Faculty members exercise discretion in applying and accepting transfer credits, but the process can leave students confused or in the dark.

FreshSplash/E+/Getty Images

Transferring from a community college to a four-year institution can be an arduous and complicated process, lacking in streamlined support for students. Researchers from the policy nonprofit MDRC analyzed three universities in Texas to unpack the faculty role in credit transfer and recommend ways to improve processes for student success.

The findings, published in a June report, point to the critical role of faculty in assessing student learning at two-year colleges, but found that transfer processes are not standardized, leaving instructors at four-year institutions to decide which credits can be transferred. The report also recommends better data collection to track transfer student outcomes.

What’s the need: For incoming students, credit transfer can seem like a black box, according to MDRC’s report.

Community college transfers often lose a large number of credits during the transition or graduate with excess credits that do not fulfill degree requirements. As a result, students are often forced to spend more time in college and additional money on courses they may have already completed.

Just over half of transfer students at public institutions in Texas earn a bachelor’s degree within four years of transferring, according to data from the Community College Research Center. One study of a Texas public four-year institution found that transfer students tend to graduate with 17 excess credits—10 more than their peers who didn’t transfer.

Unnecessary credit accumulation happens if certain credits—from elective courses, for example— do not apply to a student’s major program, or if the receiving institution doesn’t believe the community college course is a suitable substitute for its own program requirement.

Faculty members play an outsize role in this process. “As the primary decision-makers about academic content requirements within their disciplines, faculty members exercise discretion in determining how transfer credits apply to degree programs, even within the framework of state and institutional transfer policies,” the report says.

MDRC researchers sought to close a gap in the literature regarding the credit-transfer process and the role faculty play in it.

Methodology: The report outlines transfer credit evaluation at three universities in the University of Texas system: UT Arlington, UT El Paso and UT Tyler.

Researchers applied a mixed-methods approach, including semistructured interviews with 44 faculty members, advising staff, registrar officers and administrators. Analysts also evaluated student data at UTA and UTEP from transfers who entered the institutions between August 2016 and August 2022.

One of the challenges researchers faced was inconsistencies in data collection, storage and use of transfer data, meaning processes could not be compared between the two institutions.

The process: The Texas Higher Education Coordinating Board created various initiatives to facilitate transfer from the state’s 50 community college districts to the six public university systems, including the Lower-Division Academic Course Guide Manual, the Texas Core Curriculum and the Field of Study Curricula, as well as statewide reverse transfer.

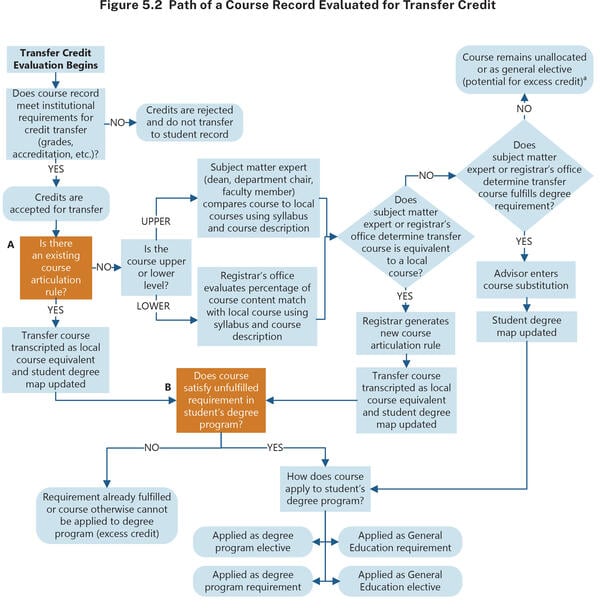

The credit transfer process involves multiple institutional departments and is often a manual process.

MDRC report

The average student’s credit-transfer process can be largely automated under existing articulation agreements or rules for general education requirements or other courses mapped out on a degree pathway.

Other courses go through a manual review to determine transferability, falling to the registrar’s office if it’s a lower-division course to fulfill general education courses or to a subject matter expert in the relevant academic division if it’s an upper-level course. Typically, the credit reviewer is the department chair, program coordinator or a faculty member who teaches similar materials.

Data showed UTA accepted 94 percent of transfer credits (the average was 54.6 credits per student), but UTEP applied only 52 percent of accepted transfer credits to a degree at the time of transfer, with 58 percent applied by graduation.

Reviewers are charged with evaluating course descriptions and syllabi to determine whether the content overlaps with a local course to fulfill that requirement.

The reviewer’s determination dictates future credit applications in the registrar’s office, creating a new course-articulation rule. If a direct equivalency is not found, credits may still be found to fulfill degree requirements as a course substitution. If a course is still not applied at this stage, it is considered excess credit.

A subjective system: The faculty interviewed were not consistent in how and when they accepted credits. Most faculty said they review the syllabus and course description and consider class session topics, assignments and assessment methods, as well as course objectives and learning outcomes.

But other instructors consider the course modality and home discipline of the teaching faculty member as well, which report authors classified as “seemingly less demonstrative of course content or student learning.”

“At times, the process of transfer credit evaluation can be somewhat subjective,” the report says. One faculty member called the process “more of an art than a science,” creating inconsistent evaluation decisions for students.

Some faculty talk with the student or review samples of their work, similar to awarding credit for prior learning, which can take more time but also allows for alternative credit awards if additional learning is demonstrated.

A lack of detailed information from the course provider can be an additional hurdle, with faculty unable to properly assess content and the student forced to submit supplemental materials, prolonging the process.

Faculty across the study also articulated significant concerns about transfer students’ academic preparation to succeed in upper-level classes, which interviewed professors tied to perceptions that community colleges are of lower quality and rigor. Data shows transfer students sometimes experience an initial GPA drop after transitioning to a four-year institution, but it’s akin to that of first-year first-time students and not a trend line through their college experience.

Articulation agreements made by faculty across institutions provide a straight path to credit transfer, but updating agreements can be a time- and resource-intensive process, faculty said.

Some instructors also expressed frustration at statewide curricular policies that require acceptance of community college courses in various programs, because it removes the faculty role in determining if courses at other institutions adequately prepare students for their own program. This has pushed some departments to reclassify lower-level courses as upper-level courses to ensure students are “academically prepared,” according to the report.

In response, the report recommends institutions develop course-equivalency policies, use data to assess transfer student academic performance and frame transfer partnerships more on student outcomes and success.

Get more content like this directly to your inbox. Subscribe here.