You have /5 articles left.

Sign up for a free account or log in.

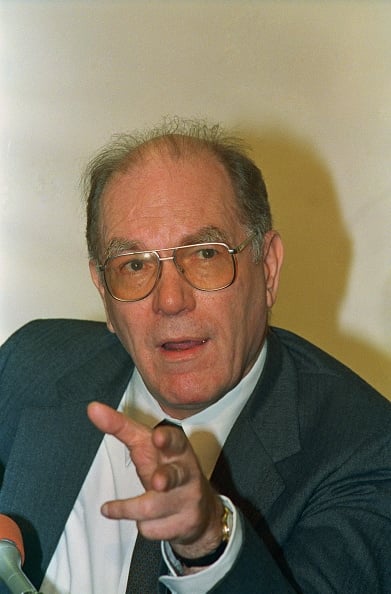

Lyndon LaRouche

Getty Images

Lyndon LaRouche died Tuesday, according to announcements by his wife. He was 96 years old. Speculation online began almost immediately: Is he really dead? How do we know?

On the other hand, LaRouche's last article or public speech appeared in late 2016, according to ex-supporters who keep an obsessive eye on such developments. Has he been dead all this time? How would we know?

When a conspiracy theorist dies, the conspiracy meta-theorizing begins -- no big surprise there. I'd be willing to bet that a large portion of it is purely tongue-in-cheek, a kind of sardonic homage by way of trying to outkook the man who made delirium into a political brand. Which is impossible, by the way. Saturday Night Live was on the verge of cancellation in April 1986 when it ran the one thing anyone remembers from that season: a parody of Masterpiece Theater with Lyndon LaRouche (played by Randy Quaid) occupying the venerable Alastair Cooke's chair, introducing the latest episode. It featured the queen of England (Joan Cusack) selling a suitcase full of heroin to Henry Kissinger (Al Franken) and his lover (Tony Danza). All three then worry that their diabolical scheme to enslave the Third World is being derailed by LaRouche's growing power.

It was preposterous, if not especially funny. LaRouche was then at his most visible and worrisome -- he had developed some contacts within the Reagan administration and was claiming credit for the Star Wars missile defense idea -- yet somehow beyond parody. Every element of "Lyndon LaRouche Theater" came right out of his movement's publications. Only the casting (with Jon Lovitz as Prince Charles to complete the scenario) was really inspired.

A dozen years ago, I wrote this column pointing out that LaRouche -- after some time in prison for credit-card fraud and few years of keeping low-key while on parole -- had his followers out recruiting a new generation of supporters from college campuses. The need to replenish the movement's ranks was urgent. His original band of disciples (many of them recruited from Ivy League universities in the late 1960s and early '70s) had shrunk as some defected from the movement and others showed a diminishing commitment. After decades of reading LaRouche's treatises and listening to his very long speeches, an appetite for the feast could not be summoned at will.

Flagging enthusiasm seems to have infuriated LaRouche even more than apostasy, and the old members who did stick around were proving less efficient at fund-raising. An influx of people in their teens and 20s who did not need much sleep and could display sufficient awe while LaRouche ran through the conspiratorial links between Aristotle and the Zika virus -- that was the movement's future.

The recruitment effort enjoyed a measure of success. LaRouche's rather canny move as the Iraq quagmire set in was to position himself as kind of elder statesman in exile of American politics at war with the George W. Bush presidency and with Dick Cheney in particular. But the momentum did not continue through the next presidential election. The LaRouche resurgence seems to have been cresting around the time my article appeared.

Even so, the proselytizing campaign had done its work. The political ghoul got a taste of fresh blood. The young members brought with them the skills needed to burnish the movement's previously dismal web presence. New faces appeared in the videos promoting LaRouche's latest warning that a financial, thermonuclear and/or bacteriological catastrophe was coming in a few months, instead of the familiar ones who'd been issuing virtually identical bulletins for 30 years.

It might be funny if not for the realization that those people were sacrificing their lives, talents and minds at the altar of a megalomaniac's narcissism. Thomas Pynchon might as well have had LaRouche in mind when, in The Crying of Lot 49, he referred to "the true paranoid for whom all is organized in spheres joyful or threatening about the central pulse of himself." Perhaps the creepiest thing about his followers' web presence now is that the spheres have kept spinning even after the pulse was gone: they quit broadcasting or publishing him in late 2016, which would have been unlikely if he were still capable of putting together a remotely comprehensible sentence.

But in revisiting LaRouche here after all this time, I want to end on an encouraging development that seems likely to be repeated, in various forms, before too long. In September 2012, several young recruits who were being groomed as leaders "compile[d], in as much detail as possible from our combined experiences, a report of the events leading up to our departures from the LaRouche organization." Running to 75 single-spaced pages, "Why We Left" is difficult to follow on first reading and has its baffling moments the second time through, too. But in brief:

The older generation of supporters is made up cliques almost as hostile to one another as they are to the younger generation of supporters. LaRouche celebrates the younger ones at every opportunity, permitting them to do the fun part of being his disciple -- i.e., research and writing -- while longtime members work the boiler rooms, phoning people who have donated in the past in hopes of squeezing more money out of them. Various backstabbings occur. The nonagenarian LaRouche becomes noticeably confused at times. He also tries to woo a woman not quite a third his age. (She thinks about it.) Most of the events unfold at one or two locations; tensions seem to ricochet in an enclosed space. The whole document feels like equal parts Peyton Place and the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders.

When approaching global catastrophes are announced, then fail to come to pass, it doesn't bother the old-timers. But it compounds the growing cognitive dissonance among some of the youth, who also suspect they will be put on the phones for fund-raising before long. Individual doubts slip into conversation; when not pushed down by the urgency of preparing for the next catastrophe, they start to accumulate, leaving a sense that the whole organization is out of touch with reality.

The authors of the document conclude that reform is no longer an option, if it ever was, and leave. This is in some ways typical: departures from a cult often come in waves. A number of convulsions thinned the LaRouchian ranks over the years, with the one in 2012 being, as far as I know, the final to occur during the founder's lifetime. The next wave will probably be easier, and not the last.