You have /5 articles left.

Sign up for a free account or log in.

Istockphoto.com/Vectorios2016

Student evaluations of teaching, or SETs, can provide a better understanding of what is working and what isn’t in classrooms. But gaining a “meaningful” understanding necessitates separating the “myths and realities” surrounding these evaluations, says a new report on the topic. That, in turn, requires data -- lots of data.

So Campus Labs, a higher education technology company with 1,400 member campuses, opened its vault to create the new, myth-busting-style report. The study included more than 2.3 million evaluation responses from a dozen two- and four-year institutions that use Campus Labs’ course evaluation system, representing something of a national sample. All were collected in 2016 or later.

First a disclaimer or two: Campus Labs sells course evaluation tools (make of that what you will). And since Campus Labs pulled the data from its own system, it couldn’t investigate questions concerning data it didn’t have -- namely, and significantly, those related to course grades or gender and ethnicity biases. These, of course, are some of the biggest points of contention among SET critics, since some studies demonstrate that students rate white male instructors differently than they rate women and racial minorities.

Even so, the Campus Labs data shine light on a number of other, commonly held beliefs about SETs used by critics to discredit them as unreliable. Those beliefs, which, again, the report refers to as “myths,” include that course evaluation comments only reflect extreme opinions.

Other, related beliefs are that students who take course evaluations outside class time are more likely to be critical in their comments and ratings and that low response rates skew evaluation results.

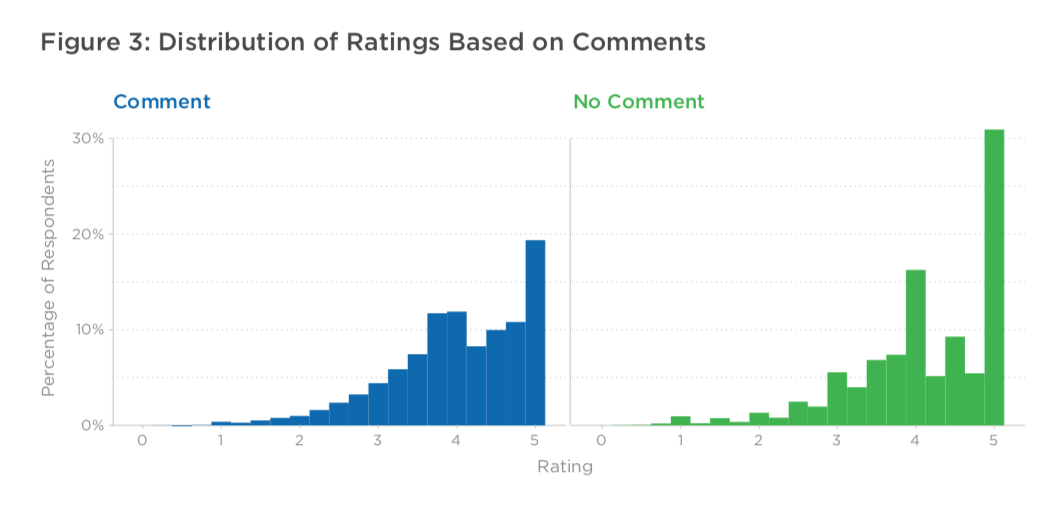

As for the extreme comments argument, Campus Labs created histograms to compare average ratings of students who left write-in comments about their professors to those who didn’t. About 47 percent of the sample did leave comments, with students at two-year institutions being more likely to do so. Ratings are 1-5, with 5 being best.

The results show a “negative skew” for those who leave comments -- and those who don’t. This suggests that concerns about “bimodal extremism” are unfounded, the report says. And among students who leave comments, a significant share rate professors above the median value. Also important is that many students who rate professors at the maximum end of the scale don’t leave any comments as to why.

Over all, the study says, the data do spark questions about how to “better design instructor feedback systems to encourage more students to leave comments -- along with helping to ensure provided comments are best utilized to assist faculty in better ensuring student success in subsequent semesters.”

As for students who take time outside class to rate professors, Campus Labs imagined that class hours are those between 8 a.m. and 4 p.m. Contrary to common concerns that only students with an ax to grind would go out of their way to rate professors, Campus Labs’ estimate found that the highest average ratings happen around 6 a.m. and the lowest happen at noon. The distribution was a bit more even for two-year institutions.

On low response rates, Campus Labs created box plots examining the average course rating for courses taught by the same professors when response rates were low as compared to when response rates were high. Researchers found a slightly higher average rating for high-response courses, but not a substantively meaningful difference. In another analysis, the response rate only explained 1.35 percent of the variance in course ratings.

Examining another belief about students -- that they have consistent attitudes across courses -- Campus Labs’ histogram analysis suggests that the overwhelming majority offer unique evaluations. Another split analysis found that students at two-year institutions were more likely to provide similar ratings across multiple evaluations, however.

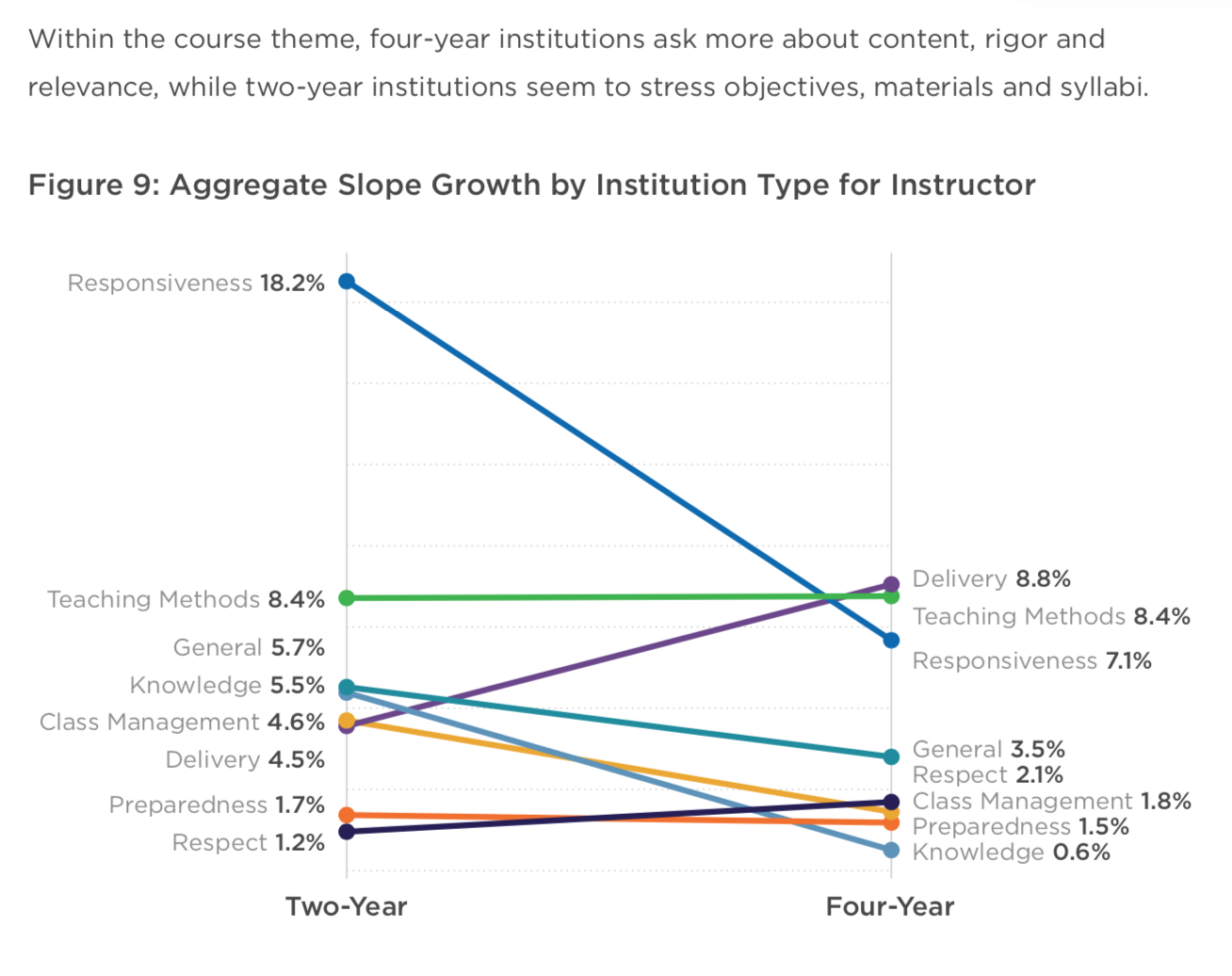

Do SETs accurately measure what faculty and administrators want? To tackle this, Campus Labs categorized about 4,000 SET questions into 23 groups focused on student growth, assessment, instructor behaviors, course design and facilities.

Based on these questions, the report found that two-year institutions were “more directly interested” in assessing instructor effectiveness while four-year institutions more routinely asked about courses, assessments and students. This may simply reflect a difference in mission, however, the report says.

“If different focal points emerge due to deliberate design choices by faculty and administrators at two- and four-year campuses, then the instruments very well could be measuring what faculty and administrators want,” reads the study. Yet if “discrepancies surface due to random chance, we may need to encourage greater intentionality in how evaluations are formulated. After all, it does not matter how many students respond if we are not asking meaningful questions that provide actionable data for faculty.”

Will Miller, executive director of institutional analytics, effective and strategic planning at Jacksonville University, formerly of Campus Labs, led the report. He said last week that it hopefully “opens the door” for campuses to have more robust conversations about when and how evaluations are conducted and about their role in measuring faculty effectiveness.

“Many important conversations about course evaluations are had without much data available, or without data being shared efficiently,” Miller said. And members often ask what qualifies a student to judge whether a course or faculty member has been effective, while administrators often highlight the role students serve as consumers rating a “service.”

In any case, Miller said that "most faculty members don’t object to the concept of course evaluations, but instead take issue with them being used as a singular measure of effectiveness." And so institutions should identify "holistic ways to evaluate the learning that takes place in the classroom, in ways that uniquely work for them." Course evaluations will continue to be a piece of that puzzle, as students are the one campus group who observe faculty members teaching consistently throughout the semester. But faculty members and administrators must "evaluate the data and work together to account for, and most importantly not penalize certain faculty for, student biases."

Institutions should also educate students on how to offer "meaningful feedback and to complete evaluations in a way that improve courses and instruction, including accounting for inherent biases," Miller said. "If an institution values critical thinking, why not tackle the issue head-on and treat evaluations as an opportunity to teach our students the skill of evaluation that many employers feel they lack upon graduation?" Satisfaction, perceptions of learning and development, and "actual performance" are all part of that, he added.

IDEA, which until recently offered its own student rating of instructional products (IDEA has since been acquired by Campus Labs), published its own myth-buster paper in 2016. It included similar findings but was based on a review of literature, not a quantitative analysis.

Ken Ryalls, president of IDEA -- which is still a nonprofit but now offers grants related to teaching and learning initiatives -- said he thought Campus Labs’ paper was of high quality.

Still, the paper is unlikely to settle the ongoing debate about what value SETs really hold. Again, the paper doesn’t address how ratings are related to course grades, or to student or teacher race or gender -- the precise factors that have caused some institutions rethink how they use student evaluations of teaching in the faculty review process, if at all.

Philip Stark, professor of statistics at the University of California, Berkeley, and co-author of a major 2016 paper demonstrating gender bias in student evaluations, called the Campus Labs report “advertising, not science.”

“It's particularly bad data analysis, including asking the wrong questions in the first place,” Stark said. Among his more specific criticisms was the lack of control group, conflating when students submitted their evaluations to when they were in class, and “no data on gender, ethnicity, grade expectations, grades or other measures of student performance.”

Based on existing research, “the strongest predictor of evaluations is grade expectations,” he said.