You have /5 articles left.

Sign up for a free account or log in.

Getty Images

Salaries for full-time, continuing faculty increased by 3.4 percent this year and 2.7 percent adjusted for inflation, according to the American Association of University Professors’ Annual Report on the Economic Status of the Profession. That’s down slightly from 2.9 percent last year, adjusted for inflation, when that figure exceeded 2 percent for the first time since the recession (although it should be noted that a one-time tweak to the way some faculty categories were reported this time around make year-over-year comparisons nominally less appropriate).

But while a continued upward salary trend following the recession is promising, the report argues it’s barely noticeable in terms of spending or saving power and doesn’t reflect a systemic threat to higher education: the decline of full-time and ranked faculty positions. The above figures are for full-time faculty members, leaving out most non-tenure-track professors.

Over the past four decades, the proportion of the academic labor force holding full-time tenured positions has declined by 26 percent and the share of full-time tenure-track positions has dropped by 50 percent, according to the report. “The increasing reliance on faculty members in part-time positions has destabilized the faculty by creating an exploitative, two-tiered system; it has also eroded student retention and graduation rates at many institutions.”

Yet the report, which for the first time offers information on part-time faculty and graduate student instructor salaries, offers a solution: that colleges and universities begin to convert part-time and full-time non-tenure-track salaries to tenure-track salaries at an additional average cost of 2 percent institutional expenditures per year. AAUP argues there are in fact economic benefits to expanding tenure, such as increasing innovative risk taking in research and increasing student retention rates.

“Higher education appears to be a crossroads,” reads the report. “Administrators and faculty members must decide whether they will travel down the familiar road, investing resources to maintain the status quo, or take a road less traveled, reinvigorating academic units and institutions with longer-term strategies that produce measurable improvements in instructional quality.” AAUP argues such improvements rest on clarification of institutional mission, strategic use of services that support student success and long-term commitment to full-time, tenure-track faculty.

Salary Outlook

First, bit more information on salary. While all ranks of continuing, full-time faculty saw a 2.7 percent average increase in 2015-16, adjusted for inflation, instructors saw the biggest bump, at 3.6 percent, followed by assistant professors (3.1 percent), associate professors (3 percent) and full professors (2.2 percent).

The average professor’s salary, across ranks, was $79,424. Average compensation, including benefits, was $94,162. Professors at private doctoral institutions made most, at $158,080 in salary and $197,418 total compensation. Unranked instructors at associate degree-granting institutions earned the least, at $48,430 in pay, but their total compensation amounted to something comparable to many of their higher-ranking peers across institution types: $80,328.

The average faculty salary across ranks at a doctoral institution was $103,715, while total compensation was $130,195. Average salary at master’s-level institutions was $75,918, and at baccalaureate institutions it was $72,104. Average salary at associate degree-granting institutions with ranks was $65,988.

Last year, faculty members at doctoral-granting institutions got the biggest raises, at 2.3 percent, not adjusted for inflation. This year it’s faculty members at baccalaureate and associate institutions, who got a 3.7 percent nominal pay increase, compared to 3.4 percent overall. Full professors got just a 2.9 percent raise, compared to nearly 4 percent raises for associate and assistant professors, and slightly bigger bumps for instructors (though this category may be inflated this year due to AAUP’s one-time survey adjustments). Those findings are relatively consistent across public, private and religiously affiliated institutions.

Across ranks and institution types, faculty members at private institutions earned the highest salaries, at $80,486, followed by those at publics, at $78,762, and, finally, those at religiously affiliated institutions, at $72,146.

Professors in New England and on the West Coast make more than their peers elsewhere, with those in what AAUP calls the “west north central,” including Kansas and Minnesota, and the “east south central” (Alabama, Kentucky, Mississippi and Tennessee) making the least.

As usual, the data differ by gender, with women across ranks and institution types earning $74,681 compared to $83,012 for men. Interestingly, and consistent with common analysis, the disparity is clustered at the top ranks: male full professors make much more than female full professors, but women earn more or as much as men at all other ranks (except for unranked faculty).

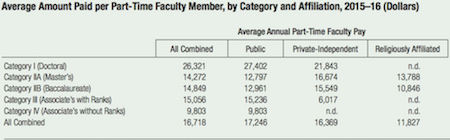

Responding to the consistent criticism that its annual survey didn’t including part-time faculty or graduate student instructor data, AAUP this year includes that information this year -- with limitations. Adjunct faculty data is reported in the aggregate, not a per-course equivalent. On average, part-time faculty members earned $16,718 from a single employer this year. Those at doctoral institutions earned most, about $26,000, while those at master’s and baccalaureate institutions earned around $14,000. Those at associate degree-granting institutions with ranks earned about $15,000, while adjuncts at such colleges without ranks earned about $9,800.

(A limitation of the data acknowledged by the AAUP is that the aggregate data don't differentiate between institutions where a typical adjunct teaches three sections per semester and an institution in which an adjunct typically teaches one. But AAUP is expanding its efforts here, hoping to eventually create as systematic a salary comparison for those off the tenure track as for those who are on it. Such a system would replace crowdsourcing efforts that have been used by some.)

Graduate teaching assistant salaries also are reported in the aggregate. Across institution types, they made $11,205 this year, on average. Those at doctoral institutions made more, at $14,345 (the salaries were roughly the same at both public and private universities). Graduate teaching assistants at master’s-level institutions made about $9,000 and those at baccalaureate institutions made about $7,042.

Average presidential salaries were $486,000 at doctoral institutions, $308,600 at master’s institutions, $290,000 at baccalaureate institutions and $225,000 at associate degree-granting institutions with faculty ranks. For chief academic officers, it’s $329,000, $202,500, $167,800 and $150,800, respectively.

AAUP’s full-time-faculty salary data, based on responses from 1,023 institutions, are more current and comprehensive than anything available elsewhere, including from the federal government. Inside Higher Ed is the exclusive provider of AAUP’s current faculty salary survey, and full data sets are available here. Institution-specific top-10 lists -- such as where full professors earn the most -- are at the bottom of this article.

The Economic Case for Tenure

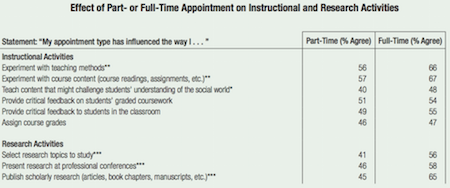

Earlier this year, AAUP conducted a survey of 2,224 instructors exploring whether one’s full- or part-time status affected one’s research and instructional activity. Full-time faculty members (both tenure-line and non-tenure-track) reported being more likely to both do and assume risk in research. They were also more likely to experiment with different teaching methods and course materials, and their perceptions of institutional support -- such whether or not there’s academic freedom on their campus -- were stronger.

AAUP’s report, which this year is subtitled “Higher Education at a Crossroads,” draws on some of those findings and other research to make its case for the economic value of tenure. It suggests that student retention -- especially for low-income students -- correlates positively with having well-supported, permanent faculty members; conversely, graduate rates decline with increasing numbers of part-time faculty members.

The paper also includes interviews with academics such as Paul Modrich, professor of biochemistry at Duke University whose groundbreaking work in DNA mismatch earned him the 2015 Nobel Prize in chemistry, and Glenn Platt, a professor of marketing at Miami University in Ohio who helped develop the “inverted,” or “flipped,” classroom model. Modrich said his position helped him to pursue “curiosity-based research” with no guarantee of returns, while Platt said he didn’t think he would have been able to experiment pedagogically as a part-time faculty member.

“Crossroads” pitches a plan to stem the erosion of the tenure system and its associated negative effects: converting contingent positions to full-time ones -- ideally those on the tenure track -- according to the institutional average for that position. Working on a variety of assumptions, AAUP estimates that that the average cost of conversion per part-time faculty position to an assistant professorship would be about $85,000, at a total cost of nearly 17 percent of American higher education spending. Converting half of these professors would represent about 8 percent of national spending.

At the institutional level, conversion to full-time instructors would cost the average institution 9 percent of total expenditures, or roughly 5 percent for half. Of course, those are averages; AAUP runs the numbers on three different kinds of institutions for comparison. At Ohio State University, with more than 58,000 students and a budget to match, the cost of converting 1,100 part-time faculty members (approximately 34 percent of the faculty) to assistant professors would cost about $107,000 each, on average, representing 2.5 percent of the total operating budget. As an interim measure, converting part-time faculty members to full-time, non-tenure-track instructors, at approximately $44,000 each, would cost 1 percent of the total operating budget.

The relative costs of such of a conversion would be much bigger at a small, private institution. At Saint Leo University, for example, converting part-time faculty members to assistant professors with benefits would cost 52 percent of total expenditures, and converting them to full-time, non-tenure-track instructors would cost 51 percent, according to AAUP. At a regional university such as the State University New York College at Oswego, the cost to convert part-time faculty to tenure-track professors would be more like AAUP’s average estimate of about 10 percent.

The conversion suggestion is sure to receive some criticism in administrator circles as being prohibitively expensive; a recent paper, for example, argued just that. But AAUP says its 10 percent estimate pertains to making such a conversion over one year. More realistically, it argues, colleges and universities could work toward conversion over time at the more modest amount of 2 percent in additional expenditures annually. To free up funds for a such an project, the report suggests cost alignment through rigorous benchmarking of instructional and research expenditures at the discipline level relative to comparable academic units at peer institutions. Understanding how to improve instruction through more effective allocation of resources can save up to 2 to 3 percent of teaching costs annually, according to AAUP. More judicious spending on athletics and facilities, and scheduling classes to maximize seat and space use also are ways to generate more funds for instruction. Donations also can be targeted for this purpose.

“If institutions are to commit to academic excellence, the conversion of contingent, part-time faculty to full-time and preferably tenure-track positions must be a central component of long-term strategic plans,” reads “Crossroads.”

John Barnshaw, director of higher education research for AAUP, said in an interview that the association has spent a long time focusing on academic freedom, tenure and governance but hopes in this report to highlight some of the overlooked economic arguments for tenure.

“There are major benefits here for institutions and the nation as a whole,” he said. “Students benefit from full-time and tenure-track faculty, and there are so many examples of how the long-term ability to innovate is associated with tenure.”

Asked how confident he was that college and universities might begin to reverse decades of movement away from the tenure track, Barnshaw said he knows it won’t happen overnight.

“What we are proposing is a gradual, long-term process in which institutions commit 2 percent of their overall expenditures toward converting part-time faculty to full-time faculty. … This is about starting faculty conversations -- where do we want to put our priorities? Do we want to focus more on the core academic missions of our institutions and reinvigorate the faculty or spend additional money on athletics and other expenditures?”

Adrianna Kezar, a professor of higher education and director of the Delphi Project on the Changing Faculty and Student Success at the University of California, works with administrators and faculty members about adjunct faculty issues. She said institutions may resist the conversion suggestion because they want more flexibility than an entirely tenure-track faculty allows for, but there are nonetheless benefits to having more faculty members on the tenure track. The “logic resonates with me of relating to reprioritizing instruction and getting more full-time faculty,” she added.

While the AAUP report draws attention to the have-nots among the professoriate, the data also show some of the best paid in academe.

Top Private University Faculty Salaries for Full Professors, 2015-16 (Average)

| 1. | Columbia University | $236,300 |

| 2. | University of Chicago | $232,400 |

| 3. | Stanford University | $229,600 |

| 4. | Harvard University | $220,200 |

| 5. | Princeton University | $215,900 |

| 6. | New York University | $205,600 |

| 7. | Yale University | $203,500 |

| 8. |

Massachusetts Institute of Technology |

$202,600 |

| 9. | University of Pennsylvania | $202,000 |

| 10. | Johns Hopkins University | $200,900 |

As has been the case in previous years, the top institution for public pay would not make the top 10 for private pay. The University of California at Los Angeles tops the list, as it did last year. Four other University of California campuses -- Berkeley, Santa Barbara, San Diego and Irvine -- also make the list.

Top Public University Faculty Salaries for Full Professors, 2015-16 (Average)

| 1. | University of California at Los Angeles | $187,800 |

| 2. | University of California at Berkeley | $178,900 |

| 3. | Rutgers University at Newark | $170,000 |

| 4. | University of Michigan at Ann Arbor | $167,500 |

| 5. | University of Virginia | $164,900 |

| 6. | University of California at Santa Barbara | $161,300 |

| 7. | University of California at San Diego | $159,800 |

| 8. | University of California at Irvine | $159,400 |

| 9. | Rutgers University at New Brunswick | $158,800 |

| 10. | University of Maryland at Baltimore | $157,200 |

The top liberal arts colleges for pay for full professors are very similar to lists from the past several years.

Top Liberal Arts College Faculty Salaries for Full Professors, 2015-16 (Average)

| 1. | Claremont McKenna College | $159,700 |

| 2. | Barnard College | $158,400 |

| 3. | Wellesley College | $157,600 |

| 4. | Pomona College | $150,400 |

| 5. | Amherst College | $147,700 |

| 6. | Swarthmore College | $146,600 |

| 7. | Wesleyan University | $145,800 |

| 8. | Harvey Mudd College | $143,800 |

| 9. | Williams College | $142,500 |

| 10. | Colgate University | $141,400 |

This year, the data show 29 colleges and universities where the average salary for an assistant professor tops $100,000. That's up from 23 institutions last year and 19 the year before.

Top 10 Colleges With Six-Figure Salaries for Assistant Professors, 2015-16 (Average)

| 1. | Babson College | $129,800 |

| 2. | Stanford University | $125,900 |

| 3. | California Institute of Technology | $124,300 |

| 4. | University of Pennsylvania | $123,200 |

| 5. | Columbia University | $121,500 |

| 6. | Harvard University | $120,200 |

| 7. | Massachusetts Institute of Technology | $116,400 |

| 8. | University of Chicago | $115,800 |

| 9. | Johns Hopkins University | $115,700 |

| 10. | New York University | $115,000 |