You have /5 articles left.

Sign up for a free account or log in.

Many people in higher education still treat online education as if it's a new phenomenon, even though some colleges and universities have been doing it for decades. That's probably partly because some institutions remain untouched by it, and at many others it has grown only in pockets of the campus -- from certain schools or programs or professors.

It's also partly because good data about online education are still relatively rare. The federal government now publishes annual data on online enrollments, and a small but growing group of researchers are paying attention to the topic. But there remains a surprising dearth of good information about how colleges approach online learning given that a third of all students take at least one online course and more institutions are putting online education front and center in their strategies.

With their third "Changing Landscape of Online Education" report (nicknamed CHLOE 3), Quality Matters and Eduventures Research are trying to change that. Their report, based on a survey of 280 chief online learning officers (up from 182 last year), supplements studies like the Education Department's annual enrollment report, the Digital Learning Compass and Inside Higher Ed's annual Survey of Faculty Attitudes on Technology.

In addition to exploring areas such as the nature of colleges' online learning offerings, the role of instructional design and how institutions gauge the effectiveness of their online programs, the study this year seeks to categorize colleges into five archetypes, or "models," based primarily on online enrollment and sector type.

The goal of the categories, Ron Legon, senior adviser for knowledge initiatives and executive director emeritus of Quality Matters, is to help institutions understand how they compare to peer institutions in areas such as course design or governance of online programs.

The five categories, and their key attributes, are:

- Enterprise institutions: these two- or four-year colleges and universities (a mix of public/private and nonprofit/for-profit) enroll more than 7,500 fully and partly online students; operate in a more centralized way than their peers; and view online learning as a core part of their enrollment and strategic plans.

- Regional public institutions: state institutions that enroll from 1,000 to 7,500 mostly undergraduate online students, a majority of which take a course load mixing in-person and online courses.

- Regional private institutions: private nonprofit colleges that enroll from 1,000 and 7,500 students, split evenly between graduate and undergraduate programs, 58 percent of which study exclusively online.

- Low-enrollment institutions: colleges (80 percent of which are private nonprofit) that enroll fewer than 1,000 students online; heaviest internal doubts about value and quality of online education; heavily decentralized.

- Community colleges: two-year institutions with fewer than 7,500 exclusively undergraduate online students, a majority (62 percent) of which are taking blended course loads.

Legon acknowledged that the five models -- to which many but not all of the institutions have been allotted -- are "far from perfect," and that they are likely to change, and probably grow, over time. Right now, for instance, many public flagship universities are not in one of the categories; most have online enrollments that are too small to be in the enterprise category but have missions that take them beyond being regional or local institutions.

The existing groupings are determined heavily by institution type (regional public, community college, etc.), and "we find that many institutions of the same type either consciously or unconsciously have adopted similar policies and postures" regarding online education. But "we do see outliers -- institutions that have 'broken out' of their natural category," Legon said.

Many of the institutions in the "low-enrollment" category, for instance, are there as "a matter of choice -- they haven't jumped on the online bandwagon, but they're using it selectively" and are "projecting very little in the way of significant growth on the near horizon."

The colleges and universities in the regional public and regional private categories, by contrast, Legon said, may be more likely to be assessing their online futures -- along the lines of the institutions discussed in this “Inside Digital Learning” article last week.

Other Findings

In addition to categorizing institutions based on the intensity of their online education presences, the new report explores a range of issues related to the strategy and operations of colleges’ online programs. (This year Quality Matters and Eduventures were joined in producing the report by Eric Fredericksen, associate vice president for online learning at the University of Rochester, who has previously conducted his own survey of senior administrators responsible for online education.) Below are some highlights.

Governance. For the first time this year, the CHLOE survey asked chief online officers if their institution has “one or more standing committee(s) or council(s)” dedicated to online learning issues.

A solid majority of the institutions (60 percent) -- remember, these are institutions that pay enough attention to technology-enabled education to have a chief online officer in the first place -- say they have such a committee, with the number highest at community colleges (80 percent) and lowest at low-enrollment four-year institutions (53 percent). A few more said a dedicated committee was in the planning stages, while about half of the rest said other institutionwide bodies handle online issues.

The panels are mostly advisory; fewer than a quarter of online learning officers who said they had online-focused committees said the body sets online policies (22 percent), and even fewer said it does strategic planning for online learning (12 percent) or coordinates across programs and schools (7 percent).

Gerry DiGuisto, vice president for strategy at ExtensionEngine, which works with colleges to design and operate online programs, said the spread of committees “reflects a meaningful shift in how important -- and, in fact, central -- online learning has become to higher ed institutions of all types. Online is less and less someone's side job or secondary responsibility. There are now more formalized and centralized structures that indicate online's strategic importance and influence within colleges and universities.”

Nature of online courses. The online courses offered by the institutions represented in the survey are wholly (34 percent) or mainly (50 percent) asynchronous, meaning that students are not required to be online at the same time as their instructors and peers. That figure was highest (92 percent) at institutions with the largest enrollments, “suggesting that significant use of synchronous delivery can inhibit online enrollment volume,” the report said.

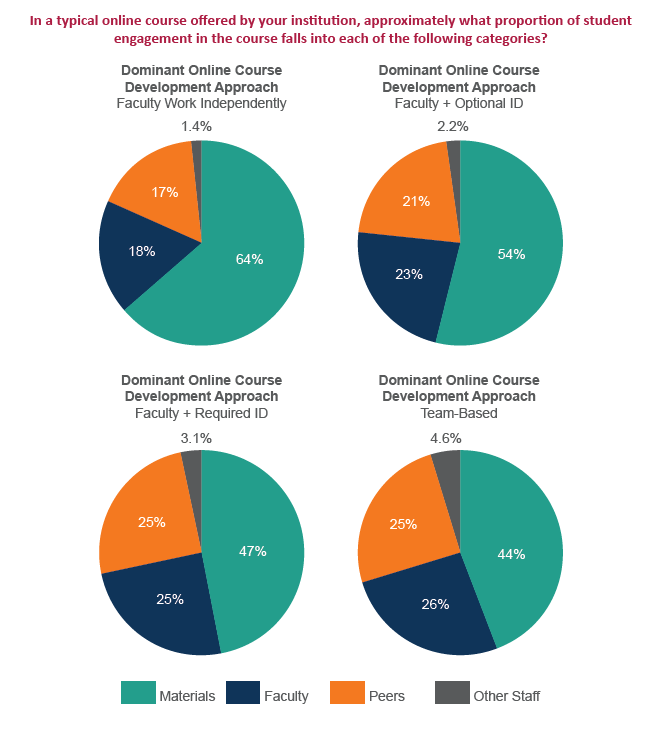

Asked to assess how much students in the typical online course at their institution engage with course material, the instructor or peers, respondents said that half of the engagement (52 percent) was with course content, 22 percent with other students and 23 percent with instructors. (Three percent was with “other staff.”)

Notably, colleges and universities that use the most interactive and collaborative approaches to building online courses produced the most interactive courses. As seen in the charts below, chief online officers reported that students had the least interaction with instructors at institutions where professors built their courses most independently, and with the least help from designers.

“It appears that faculty on their own are designing courses that have minimal faculty involvement” with students, said Legon. “It is designers who are trying to persuade them that they need to increase interaction.”

Similarly, the survey found, institutions where chief online officers were likelier to report that multiple people were involved in building online courses were also more likely to report the use of more innovative learning techniques (digital simulations, live audio and video, digital games) than were those where faculty members typically built online courses on their own.

About half of all chief online officers (48 percent) reported that faculty members at their institutions either work independently to build their courses (10 percent) or are given the option of using instructional designers (38 percent). Roughly a quarter (24 percent) say faculty members are required to work with instructional designers, 9 percent say online courses are built using a “team approach” (see related "Views" article) and 11 percent say there is wide variation. (Only 1 percent say they contract with third parties to build all their courses.)

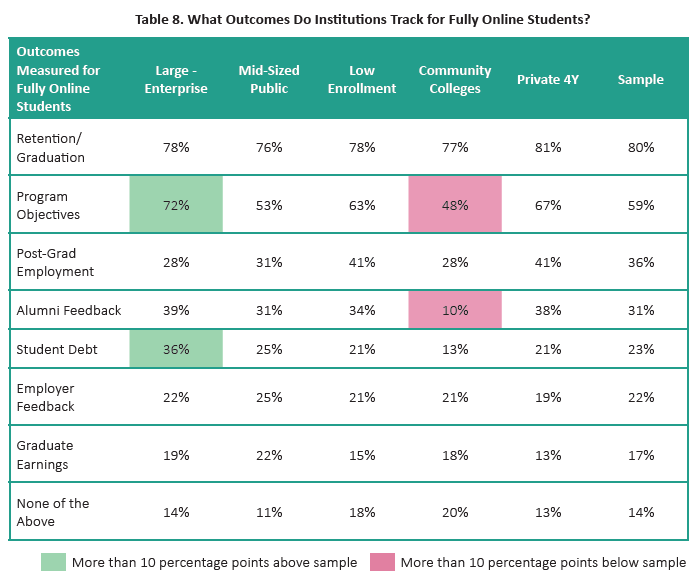

Measuring outcomes. The survey asked chief online officers what outcomes their institution tracks for students who study fully online. The dominant answer (80 percent), by far, was retention/graduation, followed by student achievement of program objectives at 59 percent. Then there's a big drop-off to the rest, including postgraduation employment (36 percent), student debt (23 percent) and graduate earnings (17 percent), among others.

"We are drawn to the conclusion that the majority of institutions are not focused on these outcomes measures and indicators of their students’ success, nor are they being pressed by regulators, accreditors and the general public to provide this kind of accountability," the report's authors write.

That may be starting to change, though, with President Trump last week joining the growing list of people calling for measuring program-level performance in higher education.