You have /5 articles left.

Sign up for a free account or log in.

maydogan/Istock/Getty Images Plus

During these times of economic instability and societal unrest, leaders are turning increasingly toward values, core beliefs and principles about what doing good looks like, as they guide their organizations. They often espouse specific values to motivate and encourage people to make important changes. For example, academic administrators may revamp their honor code or adjust policies on important topics like work/life balance to improve morale and promote healthier workplaces.

Most recently, external stakeholders are putting growing pressure on colleges and universities, often driven by a lack of support for specific institutional policies and practices that, the critics claim, lack a moral foundation. They question whether those policies and practices match those institutions’ espoused values or whether they are simply a form of virtue signaling. Thus, higher education leaders increasingly must articulate and enact specific values—such as transparency, efficiency, reliability, safety and many others—not only to improve their college or university’s performance but also to communicate to a skeptical public that they and the institution are trustworthy.

At the National Center for Principled Leadership and Research Ethics (NCPRE), we maintain that principled leadership is both the right thing and the smart thing to do. We help academic leaders at all levels reflect on the values that guide, or should guide, their work and how to pursue institutional integrity—by which we mean the alignment between espousing values and actually enacting them.

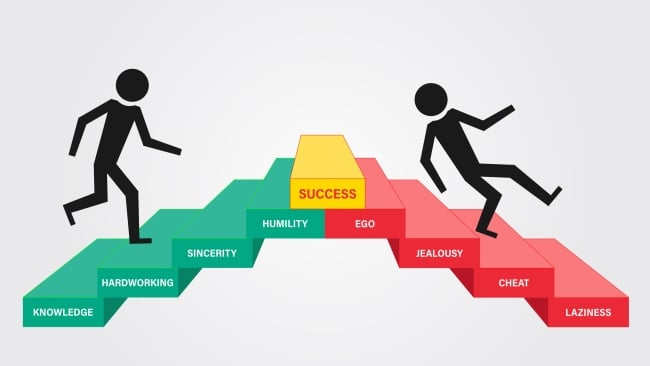

In this article, we’ll explore one example of principled leadership that has deep roots in both Western and Eastern philosophies and has recently grown in popular interest: having, and demonstrating, humility.

A Help or Hindrance?

Humility—a willingness to see oneself accurately, appreciate the contributions of others, admit error and be open to teachable moments—is increasingly seen as an important element of leadership. Humble leaders model appropriate behavior to followers and help them grow and improve, whereas leaders with a lack of humility frequently find that other people view them with some suspicion. If you want those around you to keep an open mind and be willing to change, you need to set an example.

Let’s be clear: Humility is not incompatible with a healthy self-confidence and a good understanding of one’s strengths as well as shortcomings. Indeed, it is often the confident, accomplished person who finds it easiest to be humble, because they do not see it as a threat to their authority and respect in the eyes of others. Conversely, someone who has to keep reminding people how important they are may actually be signaling insecurity.

While research increasingly demonstrates that humility in leadership builds trust and openness in organizations, being humble may not be the best approach in certain situations. For example, while seeking other people’s perspectives can be vital for improving the quality of decision-making, attempts to appease all the members of a department may, in fact, bring decision-making to a halt. Similarly, being excessively humble can sometimes go against the traditional norms of tenure evaluation. If an author, say, bends over backwards to emphasize the work of their collaborators on publications or grants, it could undercut how their own contribution is perceived.

We also need to consider how other people interpret being humble. Some may view it as a sign of weakness, or that a leader lacks the conviction, confidence or basic competence to fulfill their role. In addition, leaders with certain demographic characteristics related to race, gender or education level may not benefit from being humble as much as their peers, as it may “land” differently on others, depending on the leader’s position or identity. The very same acts of humility may be coded differently depending on context and who is speaking.

Consider, for instance, how a senior, white, male professor might be characterized in praising another’s suggestion in a departmental meeting. (“He’s so thoughtful and generous.”) Compare that to the way people could perceive a more junior, nonwhite woman performing the same action. (“She is such a sycophant—trying to make people like her.”) Humility can be seen as overly self-effacing or as a lack of competence for people who are already struggling to be taken seriously. That suggests that even moral principles such as humility may be more accessible for individuals with greater personal power or status, as opposed to those on the margins.

If you are a campus leader, learning, asking questions and cultivating curiosity are at the core of being humble, so, at NCPRE, we encourage practices like the “and stance,” “cultivating curiosity” and “personal scripts.” They not only communicate personal values and attitudes toward others but can also help you garner information and perspectives that can inform and improve your leadership.

It’s also important to ask what kind of humility, and how much humility, might be appropriate or inappropriate in certain circumstances. Being humble can look and seem different depending on the context. For example, humble leaders may use a participative approach to leadership to solicit the input of others on important issues, but when time is less abundant, they may need to act more decisively and rely on their own understanding of the problem.

How other people interpret such an act of humility can also vary. For instance, some leaders may view a participatory discussion about the promotion of someone in a college or university department as inclusive or generous, while others may see it as a drain of resources or as wasting time. Ultimately, determining the right kind or amount of humility depends on a leader’s awareness of their situation. Understanding what people need comes from open, honest relationships and a safe, trusting team environment, and humble leaders excel at fostering those conditions.

To evaluate whether being humble makes sense in an academic environment, it may be helpful to use a virtue ethics lens. Philosophers have mused that humility and other virtues may be most helpful and beneficial for people if applied at an “optimal” level—not too much, and not too little. Aristotle referred to this concept as the “golden mean” and Buddhism calls it a “middle path,” suggesting that truly moral behavior is found by balancing principles such that they avoid both excess and deficiency. This isn’t a percentage calculation, but a judgment based on experience about suitability in terms of the context and circumstance—what Aristotle calls “phronesis” or practical judgment.

That said, finding the right level of humility for your role or organization is not as easy as we might like. And as we’ve suggested, the answer may be different for different people. The skill of phronesis can only be developed through experience, learning and practice. Striking the right balance between the positive qualities of a humble leader—such as being a good listener, a willing collaborator or an eager mentor—while avoiding the potentially negative applications—such as being indecisive, never saying “no,” or trying to help too many people—is an art unto itself. One place to start is to consider the audience, roles and responsibilities needed to help your specific unit run well.

Values Work

One concept—values work, or the purposeful effort to translate abstract values into concrete practices—offers insights that you as a leader can use to incorporate values into people’s daily lives. Drawing from it, we offer a few suggestions that may help you determine whether and how humility (and other values) are appropriate for your workplace:

Take a values inventory. Consider how a value like humility might compare or compete with other values your institution prioritizes. Ask yourself:

- Which values are the highest priority at my institution?

- How might a new value like humility fit in among those other values?

- What conflicts do I foresee in trying to emphasize humility in the workplace?

Reflect on your department or unit’s strategy regarding those values. (We offer some resources here.)

Study the context. Unpack how enacting a value like humility might be interpreted in the context of your institution, department or student body. Ask yourself:

- Do the leaders at the college or university level understand and support this value in the same way I do?

- Do my departmental colleagues or students understand and support this value in the same way I do?

- Who are the stakeholders outside my department or unit whose perspectives are important? How might they understand and support this value?

Identify the specific challenges that may threaten your department or unit and how deferential or directive you might need to be in addressing them.

Explore possible adjustments. Make needed changes to allow a vital new value to “fit in” at your institution. Ask yourself:

- How might a leader who enacts a value like humility be affected in terms of promotions and evaluations?

- What are the common characteristics of successful people in my department or unit? Does this new value fit this mold?

- What might the “golden mean” of this new value look like in my department or unit? Do we need to adjust any systems to accommodate that?

Also, consider the changes you may need to make due to cultural or generational differences in your unit.

Introducing and making new values, such as humility, part of a department’s culture takes time and patience. It may even be that some values do not belong, regardless of how benevolent or useful they may seem in principle. But articulating what your values are and trying to engage with new ones are worthwhile practices. They can yield positive results for leaders in higher education in terms of both credibility and effectiveness.