You have /5 articles left.

Sign up for a free account or log in.

Elizabeth Redden/Inside Higher Ed

Weirdness is in the eye of the beholder and whether to avoid it or seek it out, a matter of sensibility. Next year is the centenary of the first Surrealist Manifesto, in which André Breton, the founder of the movement, declared war on “the reign of reason” and “the waking state”—instead celebrating “the incurable human restlessness” exemplified by a taste for the marvelous and the anomalous.

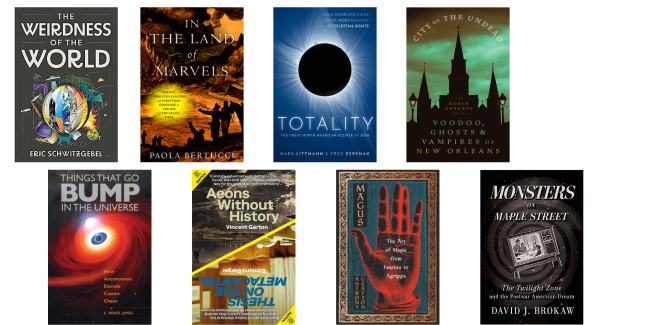

In going over the fall’s new titles from university presses, I keep noticing books that look promisingly weird. Some authors would undoubtedly bristle at the word “weird,” so let’s just categorize their subject matter as consisting of marvels and anomalies. Flagged here are some titles that caught my eye, described with quotations taken from the publishers’ listings. For restlessly curious readers only …

Appropriate as a starting point would be Eric Schwitzgebel’s The Weirdness of the World (Princeton University Press, January), a philosophical inquiry into the enigmatic status of consciousness in a universe it did not create … or did it?

Could reality be a simulation? “Might virtually every action we perform cause virtually every possible type of future event, echoing down through the infinite future of an infinite universe?” Our powers of comprehension are mighty, but trip over themselves. The author’s “Universal Bizarreness” thesis maintains that “every possible theory of the relation of mind and cosmos defies common sense,” and is accompanied by the “Universal Dubiety” thesis that “no general theory of the relationship between mind and cosmos compels rational belief.”

More sanguine in its view of what humans can and do know, C. Renée James’s Things That Go Bump in the Universe: How Astronomers Decode Cosmic Chaos (Johns Hopkins University Press, November) nevertheless keeps the mind-boggling qualities of the universe always in view. It went through aeons of spasmatic transformation following its “violent birth” in the Big Bang, including “blasts, implosions, cosmic cannibalism, collisions, and countless other fleeting energetic events.” The author, an astronomer, shows how her international colleagues “are using pioneering research techniques to explore everything from the very first explosions in the universe to the dark energy that could destroy it all."

Commanding dark energies was part of the skill set claimed by the cohort of Renaissance intellectuals analyzed by Anthony Grafton in Magus: The Art of Magic from Faustus to Agrippa (Harvard University Press, December). The magus—a learned practitioner of ceremonial magic—had a first-hand acquaintance with angelic and demonic entities. It was a dangerous profession, infringing on religious authorities’ turf and easily tarred with charges of sorcery, but one in demand: the magus was part of “political and social milieus” that included “the circles of kings and princes.”

Magi “probed the limits of what was acceptable in a changing society, and promised new ways to explore the self and exploit the cosmos.” Grafton’s study is long-awaited: he mentioned working on it when I profiled him more than twenty years ago.

Among other services a magus might render to his royal patrons were espionage and cryptography—not forms of magic, but literally occult (i.e., secret or hidden) practices. Paola Bertucci’s In the Land of Marvels: Science, Fabricated Realities, and Industrial Espionage in the Age of the Grand Tour (Johns Hopkins University Press, October) investigates an 18th century French physicist’s involvement in an “ambitious intelligence gathering [operation] masked as scientific inquiry.”

When Jean-Antoine Nollet (the savant in question) travelled through Italy in 1749, the cover story was that he was investigating reports of miracle cures via electricity. In fact, he was on “an undercover mission commissioned by the French state to discover the secrets of Italian silk manufacture and possibly supplant its international success.” Once back home, Nollet wrote “a highly influential account of his philosophical battle with his Italian counterparts, discrediting them as misguided devotees of the marvelous.” It sounds like spy fiction: an agent sowing disinformation in the wake of committing industrial espionage.

The late Robert Anton Wilson wrote mind-bending books—most notably his fictional Illuminatus! trilogy—that occupied a large place in the American counterculture of the post-hippy era. Playing with conspiratorial thinking as a key to imagining alternate realities, he made it hard to tell just where satire left off and his actual beliefs began. Some hints might come from Gabriel Kennedy’s Chapel Perilous: The Life and Thought Crimes of Robert Anton Wilson (MIT Press, November), the first biography of a figure somehow both influential and marginal at the same time.

It will double as a survey of “the pulp venues, quack pamphlets, and oddball websites through which his work was usually distributed, allow[ing] him to quietly become one of the most prescient American writers of the 20th century, and one of the 21st’s most salient.”

One notably Robert Anton Wilson-esque new volume is Aeons without History/Thesis on the Metacartel (Urbanomic, distributed by MIT Press, November), which mimics a long-vanished pulp-publishing format: the two-books-in-one science fiction paperback. “A historian and a political economist investigate the occult forces that control history,” we’re promised.

Vincent Garton’s half, “Aeons Without History,” invokes the theoretical specter of a world “of stasis and directionless suspense … in which empires rot and prophecies fail,” of “gloom, distant yet uncomfortably familiar … in which time itself became directionless, seemingly reduced to ruin.”

The theoretical fiction of “a meta-historical conspiracy for our times” (a Wilsonian notion, if ever there was one!) is elaborated in Edmund Berger’s “Thesis on the Metacartel,” which imagines “technocratic planners outlin[ing] schemes for the centuries to come, acting in concert with countless spooks and hired agents who thrive in the secret anarchy of the world system.”

Rod Serling’s invitation to join him in another dimension is more evocative now of nostalgia than 21st-century dread, but David J. Brokaw’s Monsters on Maple Street: The Twilight Zone and the Postwar American Dream (University Press of Kentucky, August) underscores his challenge to the “idealized version of American life sustained by the nuclear family and bolstered by a booming consumer economy” projected by American entertainment in the early post-World War II period. Reframing “white American wish fulfillments as nightmares, rather than dreams,” Sterling and his collaborators used “science fiction, horror, and fantasy to challenge conventional thinking … around topics such as sexuality, technology, war, labor and the workplace, and white supremacy.”

Robin Roberts explores a three-dimensional, live-action sector of the Twilight Zone in City of the Undead: Voodoo, Ghosts, and Vampires of New Orleans (Louisiana State University Press, September). By virtue of its location “near the mouth of the Mississippi River,” New Orleans occupies “a liminal status between water and land,” with “its Old World architecture and lush, moss-covered oak trees lend[ing] it an eerie beauty.” It is also where “spiritual beliefs and practices from Native American, African, African American, Caribbean, and European cultures” have converged. Local traditions and mass-media narratives depict the city as home to Voodoo, ghosts, and vampires: “the paranormal gives voice to the voiceless, including victims of racism and oppression, thus encouraging the living not to repeat the injustices of the past.”

Finally, looking from earth to sky, we have Mark Littmann and Fred Espenak’s Totality: The Great North American Eclipse of 2024 (Oxford University Press, September)—a revised edition of a book originally appearing just ahead of the total eclipse of 2017. The focus now is on the one that will be visible (weather permitting) in Canada, Mexico and the United States on April 8, 2024.

Offering “information on how best to photograph and video record an eclipse, as well as abundant maps, diagrams, and charts, as well as covering the science, history, mythology, and folklore of eclipses,” it promises “to help readers understand and safely enjoy all aspects of solar eclipses.” For verily, on that day, the heavens will darken, and you might want a handbook.