You have /5 articles left.

Sign up for a free account or log in.

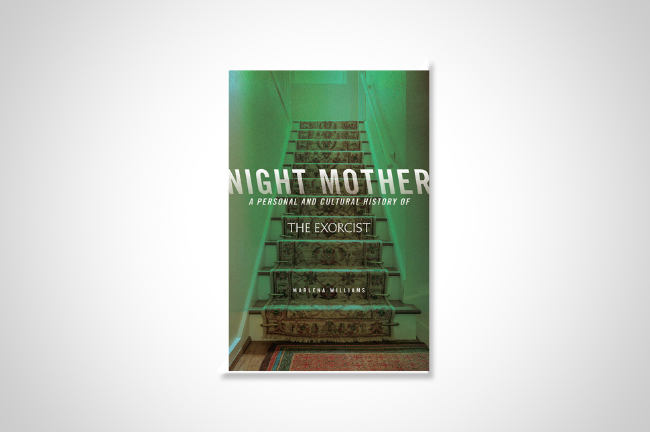

Ohio State University Press

Fifty years ago, Ellen Burstyn played the mother of the possessed girl in The Exorcist—a character she has reprised in a sequel, The Exorcist: Believer, now in theaters. Publicity coverage has been referring to Burstyn’s “return to the franchise,” which is a phrase to make one’s blood run cold, embodying as it does the prime directive of 21st-century Hollywood: find something that works, then beat it to death.

It’s not the first time someone has tried to squeeze another gallon of green phlegm from what William Friedkin (who died in August) first put on screen. But boiling down the original into the replicable elements of an established entertainment brand will never yield anything with the power to fascinate and even haunt viewers to the degree Marlena Williams achieves in Night Mother: A Personal and Cultural History of The Exorcist (Ohio State University Press). “I believe,” she writes, “that a single film, or even just a few frames of a single film, can enthrall, disturb, and perplex an individual for their entire life. It happened to my mother, and it happened to me.”

That ambivalence—a mixture of fascination and revulsion—was felt by much of the movie-going public in 1973, for reasons the author considers in the book’s more historical and analytic pages. Putting The Exorcist in the social context of an earlier decade can account for some of its immediate relevance, but not for its intense and specific hold on individual viewers across at least a couple of generations. Each section of the book moves between passages of memoir and cultural critique while somehow keeping them in sync as ways of reckoning with a uniquely effective piece of cinematic art.

Not to go too far off on a personal narrative tangent myself, but when The Exorcist first arrived in movie theaters, it also had an effect on fifth graders—who, of course, could not go see it yet, but nonetheless grasped that it was a focal point of severe grown-up anxieties. Word on the playground was that it could not only make you faint or barf (that was mentioned in every news report) but even go insane or—the very worst-case scenario—become possessed by demons, though the likelihood of that last possibility was up for debate.

After the movie left the theaters, at least a few years would pass before many of us got the chance actually to see it. Unavailability cannot have reduced the aura of dangerousness. But by Williams’s account, it lingered well into the age of VHS and perhaps beyond. “Don’t ever watch The Exorcist,” Williams’s mother insisted during her Catholic girlhood in a small Northwestern town in the 1990s—echoing a commandment from her own mother, whom the author describes as “a deeply religious woman who chain-smoked Pall Malls and swore like a sailor.”

It goes almost without saying that Williams’s mother, then an adolescent, violated the injunction as soon as possible, sometime in 1974. She immediately regretted it. Bracing oneself against potential sensory overload involves opening oneself to it, even so, and can prime the pump for adrenaline. Williams herself had what sounds like a less wrenching first encounter with the film (for one thing, she saw it on a small screen), but violating a taboo has its own effects, which can take a while to work out.

Williams’s analysis of the movie largely follows the lead of the film theorist and critic Robin Wood, who did not discuss The Exorcist itself at much length but developed an understanding of the horror genre that fits it well. In general, horror depicts the eruption of something monstrous—unnatural, inhuman, violent or otherwise disruptive—into what most characters regard as a stable, normal order of things. The story arc involves escaping from or destroying the threat, whereupon order is restored, recreated or at least patched up until the sequel.

Drawing on a bit of Marx and a lot more Freud, Wood interprets the monstrous element to be a proxy or avatar of forbidden or unruly desires, emotions and social forces. The horror genre offers audiences the vicarious pleasure of seeing the normal order of things collapsing as repressed impulses run amok, followed by a reinforcement of the legitimacy and security of the status quo once the monster has been killed, the ghost banished, etc.

Fortunately, more imaginative and daring variations are possible, with the early Frankenstein films directed by James Whale being a classic example. Boris Karloff plays the monster as a deeply sympathetic character. Wood’s early critical essays came in the wake of numerous horror films of the 1960s and ’70s that celebrated the return of the repressed or treated the established order as itself monstrous.

Williams takes The Exorcist to be, in large part, an antifeminist horror movie on the cusp between countercultural disorder and the rise of a politics of aggressive nostalgia for Leave It to Beaver norms. Burstyn’s character is a single mother with a successful career as an actress (we see her at Georgetown University, on the set of a movie about campus protest) with no man in her life, and no God, either. She is close to her sweet, innocent daughter (played by Linda Blair) and soon utterly out of her depth. The details of the possessed girl’s behavior may be omitted here, but the viewer will not soon forget them. Two priests conduct a harrowing course of rituals and prayer and ultimately drive the demon out of her, but only at the expense of their lives. The daughter returns to sweetness and innocence and remembers nothing, thanks to the heroic efforts of a quintessentially patriarchal institution.

The author shores up this assessment of The Exorcist’s context and story arc with information from the film’s production history, including conflicting testimony by Friedkin (the director) and Blair over whether she understood the behavior she was acting out in the notorious scene with the crucifix. He claimed that she told him she knew all about masturbation and that, like, everyone did it, man. (I’m not quoting him, but such is very much the vibe.) Blair’s later statement that she was a child following detailed directions without understanding them sounds altogether more credible.

Williams has a revisionist take on the much-celebrated “New Hollywood” era of young auteurs of Friedkin’s generation, calling it “a largely reactionary movement dominated by men in every way possible,” using film “to redefine their masculinity and put women back in their place.” (See, inter alia, The Godfather.) But she also acknowledges that The Exorcist is “one of the few New Hollywood films in which a single woman and her adolescent daughter play prominent roles and receive just as much, if not more, screen time than the two leading men.”

It was unusual enough in any film, let alone a horror film, to give it layers of implication that may account for The Exorcist’s lasting hold on many viewers. As Williams writes, it “brilliantly dramatizes … [the] close emotional bond” between mother and daughter “and then exaggerates the brutality of its eventual decline, showing the ways deep love can quickly devolve into hate, how those things can, and often do, exist at the exact same time.”

Williams’s multigenerational personal narrative of viewer responses to The Exorcist takes her analysis beyond anything readily paraphrased. Read it for yourself.