You have /5 articles left.

Sign up for a free account or log in.

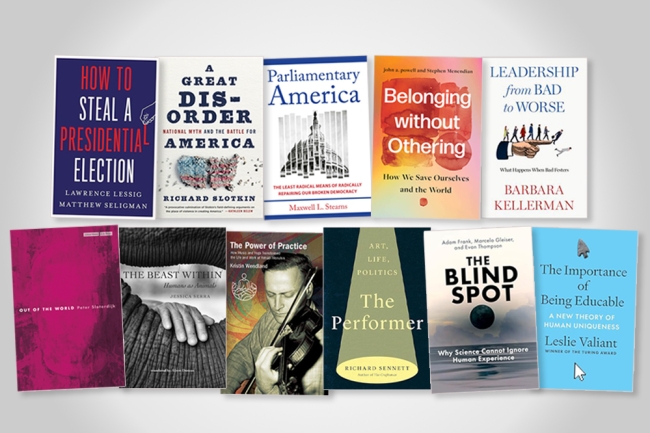

Photo illustration by Justin Morrison/Inside Higher Ed

Fall’s downturn in the output of new university-press books on contemporary political life in the United States has come to an end, to judge from the spring catalogs now available. The publishing season and the primary season overlap, and the roundup below represents just a sampling of the new books announced. The list is balanced with a number of forthcoming titles that look beyond the problems addressed, or ignored, by candidates.

The passages quoted here are culled from catalog descriptions; publication dates are taken from press websites.

No way around it: The award for hottest of hot takes goes to Lawrence Lessig and Matthew Seligman, whose How to Steal a Presidential Election (Yale University Press, February) explores the “perfectly legal ways of overturning election results” available that “would allow a political party to install its own candidate in place of the true winner … from vice-presidential intervention to election decertification and beyond.” The authors aim to “shore up the insecure system for electing the president before American democracy is forever compromised” by flagging “correctable weaknesses in the system, including one that could be corrected only by the Supreme Court.” The news cycle brings frequent reminders that American electoral politics is cultural warfare conducted by other means. Richard Slotkin’s A Great Disorder: National Myth and the Battle for America (Harvard University Press, March) treats the polarization between Red and Blue as the product of diverging conceptions of American history and citizenship. Red America embodies “a frontier-inspired hostility to the federal government,” plus the “racially exclusive definition of American nationality” expressed by symbols of the Confederacy. Blue America, “taking its cue from the protest movements of the 1960s, envisions a limitlessly pluralistic country in which the federal government is the ultimate enforcer of rights and opportunities.”

The proverbial wisdom has it that fish always rots from the head down. The process is inexorable—and nobody has figured out how to reverse it. Barbara Kellerman’s Leadership from Bad to Worse: What Happens When Bad Festers (Oxford University Press, February) warns that bad leadership tends, in political and business organizations alike, to devolve “from bad to worse” in a “steady, as opposed to hasty” process—but is no less insidious for that.

“[O]nce bad burrows in, it digs in … deeper and then deeper” unless slowed or halted by some outside force. Bad leaders attract bad followers, introducing new dangers. The decay proceeds through phases, “each more ominous and ultimately dangerous than the one preceding.” Recognizing the stages of development identified by the author may make it possible “to slow or, preferably, to stop" this progression.

Renovating U.S. political institutions is the course Maxwell L. Stearns suggests in Parliamentary America: The Least Radical Means of Radically Repairing Our Broken Democracy (Johns Hopkins University Press, March). Three structural changes would bring about a “robust multiparty democracy,” Stearns suggests: “expanding the House of Representatives, having House party coalitions choose the president, and letting the House end a failing presidency based on [a vote of] no confidence.” These changes would be introduced through Constitutional amendments. Given the long odds against dismantling even the profoundly antidemocratic Electoral College, the author’s proposals, however nonradical, nonetheless seem faintly utopian.

The definition of politics as “show business for ugly people” has been attributed to any number of individuals. I would like to nominate Aristotle: as an author on both subjects, he would have been well-placed to make the observation.

Be that as it may, Richard Sennett’s The Performer: Art, Life, Politics (Yale University Press, April) responds to a “cluster of demagogues [that] has recently dominated the public realm through their powers as actors.” Performers on the stage, screen and podium use “the same nonverbal realm of bodily gestures, lighting and blocking, costuming, and stage architecture,” for ends “malign or sublime, repressive or liberating.” A former professional cellist before turning to sociology, Sennett has already published significant work on craftsmanship and the public sphere, and considers how the “ambiguous art” of performance “might become more ethical.”

Kristin Wendland’s The Power of Practice: How Music and Yoga Transformed the Life and Work of Yehudi Menuhin (SUNY Press, January) looks at the nexus between performance and values from another angle. The eminent British violinist was a dedicated practitioner of yoga and a friend of “renowned yogi” B.K.S. Iyengar who “applied his understanding of Iyengar’s teachings to his philosophy of musical practice, creating new ways to approach the teaching of violin technique.” The book considers how the physical and spiritual discipline shaped his role as “performer, teacher, and humanitarian” with an international influence.

Several new books ponder how humankind found its footing in this world—and whether it remains firmly enough planted. Leslie Valiant’s The Importance of Being Educable: A New Theory of Human Uniqueness (Princeton University Press, April) identifies “educability” as “the unique capability that has been so foundational to our achievements and civilization.” The author compares human “educability” with similar information-processing capabilities of our fellow animals as well as artificial-intelligence technology: “It sets our species apart, enables the civilization we have, and gives us the power and potential to set our planet on a steady course.” But the potential has developed unevenly. True, “we can readily absorb entire systems of thought about worlds of experience beyond our own,” but “we struggle to judge correctly what information we should trust.”

A fine-tuning of our educability system, so to speak, is the aim of The Blind Spot: Why Science Cannot Ignore Human Experience (MIT Press, March) by Adam Frank, Marcelo Gleiser, and Evan Thompson. The authors (an astrophysicist, a theoretical physicist and a philosopher, respectively) acknowledge the Enlightenment legacy of generating and applying knowledge through the sciences. But “we’ve gotten stuck thinking we can know the universe from outside our position in it.”

This creates a blind spot regarding “humanity’s lived experience as an inescapable part of our search for objective truth.” As a corrective, the authors propose that science be understood “not as discovering an absolute reality but rather as a highly refined, constantly evolving form of human experience.”

Even more big-picture perspective is available in Peter Sloterdijk’s Out of the World (Stanford University Press, May). Originally published in German in 1993, it now joins the avalanche of recent translations of the philosopher’s books.

Undertaking “a cross-cultural and transdisciplinary meditation on humanity’s tendency to refuse the world,” Sloterdijk proposes “a theory of consciousness as a medium, tuned and retuned over the course of technological and social history.” At some point the tuning got stuck, resulting in “the mania and world-escapism of our cybernetic network culture” that Sloterdijk has written about in many subsequent works.

A particular blind-spot or variety of world-rejection concerns Jessica Serra in The Beast Within: Humans as Animals (Johns Hopkins University Press, January). We (wrongly) “think of our animality as standing in opposition to our humanity” and assign ourselves “a superior place in the hierarchy of organisms on Earth.”

Incorporating “discoveries made by ethologists, anthropologists, and archeologists,” the author “demystifies ideas about how different animals are from humans.” Senna examines such human interests as “sex, morality, emotions, intelligence, and family." Seen “in light of their animal roots,” our characteristic behaviors look far from unique. Some humility seems in order.

Against “humanity's inclination to fracture itself” along various lines, john a. powell and Stephen Menendian’s Belonging Without Othering: How We Save Ourselves and the World (Stanford University Press, April) advocates going beyond “rigid self-concepts while celebrating our rich diversity.” Writing that “the struggles faced by marginalized groups can only be fully grasped through the lenses of othering and belonging,” their “paradigm” calls for “turn[ing] toward one another—even if it involves questioning seemingly tolerant and benevolent forms of othering. Crucially, the authors assert that there’s no inherent or inevitable notion of an ‘other.’”

As for “belonging,” one imagines that HR workshops are involved.

On the other hand, HR may yet be abolished by AI. The prospect of a fully dehumanized workplace looks ever more literal. Allison J. Pugh’s The Last Human Job: The Work of Connecting in a Disconnected World (Princeton University Press, June) acknowledges that “even jobs requiring high levels of human interaction are no longer safe,” including the work she calls “connective labor.”

The term covers “work that relies on empathy, the spontaneity of human contact, and a mutual recognition of each other’s humanity.” Her interview subjects range from “physicians, teachers, and coaches to chaplains, therapists, caregivers, and hairdressers.” The day of the robot therapist is not difficult to imagine, but these professions seem resistant to being automated. Yet connective labor is under pressure even so: “profit-driven campaigns imposing industrial logic shrink the time for workers to connect, enforce new priorities of data and metrics, and introduce standardized practices that hinder our ability to truly see each other.”

The author pleads for 21st-century society “to recognize, value, and protect humane work in an increasingly automated and disconnected world.” The ties binding it together are dangerously fraying as it is.