You have /5 articles left.

Sign up for a free account or log in.

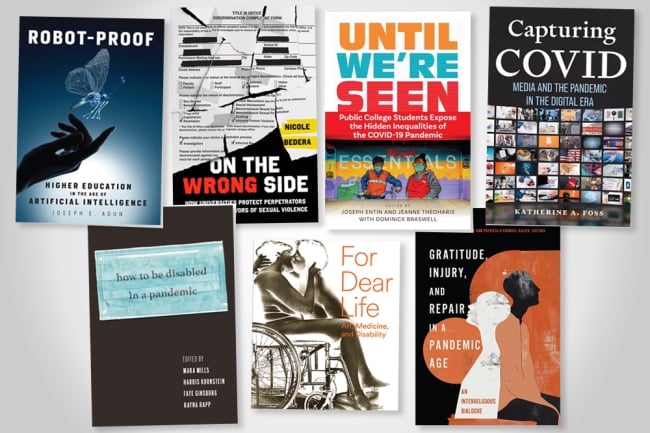

MIT Press | University of California Press | University of Pennsylvania Press | University of Massachusetts Press | NYU Press | Museum of Contemporary Art San Diego | Georgetown University Press

In the column that ran just after Memorial Day, I flagged a number of forthcoming books from university presses likely to interest a broad range of Inside Higher Ed readers. With the Labor Day weekend bringing summer to a close, it’s a good moment to note a few more titles—starting with some on higher education itself. (Quotations below are taken from publishers’ descriptions.)

The revised and updated edition of Joseph E. Aoun’s Robot-Proof: Higher Education in the Age of Artificial Intelligence (MIT Press, October) comes seven tumultuous years after the original. In the meantime, AI has moved into doing work that once seemed unprogrammable and irreducibly human. (I expect the first AI-generated New York Times best seller will be announced within a couple of years at most.) Professionals must now learn “not only to be conversant with these technologies, but also to comprehend and deploy their outputs.”

The author, the president of Northeastern University, expands upon his call for “a new curriculum, humanics, which integrates technological, data, and human literacies in an experiential setting.” He also calls for universities to join “a social compact with government, employers, and learners themselves” to prioritize lifelong learning and make the university a “force for human reinvention in an era of technological change.”

Nicole Bedera presents a “comprehensive account of the inner workings of the secretive Title IX system” in On the Wrong Side: How Universities Protect Perpetrators and Betray Survivors of Sexual Violence (University of California Press, October), finding that entrenched structures and practices “punish survivors who come forward … threatening the degrees that brought them to college in the first place,” while “protecting—or even rewarding—their perpetrators.”

Social, medical, educational and labor history overlap with one another in Until We’re Seen: Public College Students Expose the Hidden Inequalities of the COVID-19 Pandemic (University of Pennsylvania Press, August), a collection of firsthand recollections edited by Joseph Entin and Jeanne Theoharis, with Dominick Braswell.

The contributors are “predominantly young, working-class immigrants and people of color” who were studying at Brooklyn College and California State University, Los Angeles, between 2020 and 2022. The oft-repeated sentiment of those days that we were “all in this together” seems not to have squared with the experience of students who “drove delivery trucks, worked in private homes, cooked food in restaurants for people to pick up, worked as EMTs, and did construction”—labor that could not be done from home.

Another collection revisiting the impact of COVID is How to Be Disabled in a Pandemic (NYU Press, February 2025), edited by Mara Mills, Harris Kornstein, Faye Ginsburg and Rayna Rapp. The book focuses on the experiences of disabled people living in the five boroughs of New York City—who were “among those hardest hit by the pandemic”—and also considers the ways in which “disability expertise has become widely recognized in practices such as accessible remote work and education, quarantine, and distributed networks of support and mutual aid.” Contributions by “disability scholars, writers, and activists” elaborate on “the dialectic between disproportionate risk and the creativity of a disability justice response.”

The history of that dialectic is the focus of For Dear Life: Art, Medicine, and Disability, a volume edited by Jill Dawsey and Isabel Casso and published by the Museum of Contemporary Art San Diego in conjunction with an exhibition running from this fall into early winter. (The book is distributed by University of British Columbia Press and out in October.) It focuses on “an intergenerational group of artists from across the United States” that emerged in the 1960s and ’70s and remained active through the pandemic and beyond. Their engagement with themes of “vulnerability, illness, impairment, and forms of unruly embodiment” served to reframe disability “as a refusal to conform to the pace, architecture, and economic conditions of contemporary life”—and “to highlight relations of mutual dependence and practices of care.”

Nurturing “relations of mutual dependence and practices of care” remains a perennial concern of the world’s spiritual traditions. Gratitude, Injury, and Repair in a Pandemic Age: An Interreligious Dialogue (Georgetown University Press, December), edited by Michael Reid Trice and Patricia O’Connell Killen, combines “scholarly insight” and “personal reflections on what it means to work through such a life-changing event” as COVID from within “the Jewish, Muslim, Hindu, nonbelieving, and Christian traditions.”

With a list so clearly meant to be inclusive, one omission seems particularly unfortunate. Besides being a world religion, Buddhism places suffering and compassion at the center of the book’s attention: the struggle to “make meaning in the moments when life confronts us as partial, fragmented, and fragile.” As it does for everyone, of course, whatever we believe, or don’t.

Finally, Katherine A. Foss’s Capturing COVID: Media and the Pandemic in the Digital Era (University of Massachusetts Press, January) reconstructs the pandemic as, in effect, a self-documenting news event. Events unfolded in “a 21st-century digital landscape of instant communication and abundant online platforms, with older models of news and entertainment media mingling with new types of citizen-produced content,” all in real time.

A constant flood of “press releases, interviews, websites, blogs, social media posts, and other publicly available materials” kept the public “informed and connected”—or, in other cases, delusional and hostile. The author “makes sense of how this contemporary media landscape shaped the public’s knowledge and perceptions” of what still feels like a turning point in this no longer new century.